As curator of the group exhibition “Political Body II”, the Brussels-Tunisian artist Ichraf Nasri once again casts herself as a beacon of social and artistic empowerment. Her personal mission and that of the organisations she works for: make everyone outside the norm visible and provide role models.

Artist Ichraf Nasri: ‘Some people flinch when we talk about race. But we must do it’

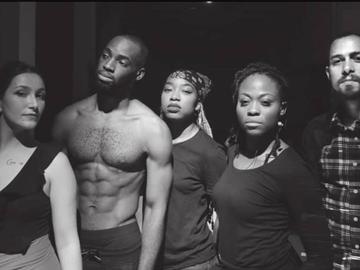

© Anne Sophie Guillet

| Ichraf Nasri: "For a long time I didn’t know what my artistic identity was, precisely because I didn’t find anyone who looked like me."

When we point out during our video call to Ichraf Nasri that our colleagues had the impression that they had seen her name popping up “here and there” over the past few months, she laughs: “Here and there? Maybe the issues that have been bothering me for a long time are now being swept under the carpet a little less, there is finally a process of awareness starting that is making visible what has long remained hidden.”

But if it were up to her, things could be even better. As a child, the now 32-year-old artist and curator dreamed of becoming a circus performer and actress, but that was far too complicated in the dictatorship of her homeland. In the end, an art education was the path to a greater social engagement for her. Her later experiences in Brussels, during, but especially after additional studies at La Cambre, brought artistic inspiration. Above all, they inspired her to become an advocate for a generation of young feminist artists, who take abrasive positions on race, class and gender, precisely because they challenge privileges that are all too often taken for granted.

A look back at her own trajectory quickly reveals where her commitment, which is rampant in her oeuvre and with emancipatory non-profit organisations such as Xeno~ and FEMMESProd, comes from.

You were still studying in Tunisia when the Arab Spring started in 2010. How did you experience that period?

Ichraf Nasri: As a teenager, I lived in a more protected environment. At university, I started to see things in perspective and became more activist. I set up a student syndicate, which was the only way to do politics, more or less. During the revolution, things were violent with confrontations with the police. But at the same time it was very exciting. Everyone came out onto the streets. We had been waiting for this for years. I took part in the protests as a citizen, but also as a reporter. I filmed the demonstrations and reported on the region around Sousse, the coastal town where I was studying. Even though there would be many disappointments later on the political and economic front, it was a turning point.

Your militancy would take shape mainly through the organisation of film clubs, a way of secretly educating the public and moulding critical mass in dictatorial or authoritarian regimes.

Nasri: Indeed! For me, culture was already a kind of disguise to weigh on society. We had to walk on eggshells, because there was a lot of censorship and control. Film showings that in any way dealt with the Tunisian political situation, anything with nudity and Islam propaganda was forbidden. Censorship was fierce on both the left and the right of the political spectrum. I first founded the Sousse film club. After four years, I moved to Sfax to create an even more committed cinema club. I could do that because the region was more rural, civil movements were stronger and culture was less accessible. Even then, I considered speaking to people who were hard to reach about what was happening in society a challenge.

A struggle must be fought so that everyone can find their place in society without being judged

Eventually you ended up in Brussels in 2013. What was your first impression?

Nasri: I was able to come here to study because my mother had emigrated and lives in the Netherlands. There was no money for going out, so those first years, I was mainly studying diligently. I couldn't afford not to succeed. I especially remember that people did not look like me and I became aware that I was not white, although I had always felt I was because, for a Tunisian, my skin colour is very clear. Confronting a non-Mediterranean and non-Islamic culture was also a challenge, although I am not necessarily religious. I thought a lot about how people viewed me here and how that affected how I saw myself. For example, the art history lessons were quite an adjustment. Together with people who did not look like me, I found myself studying people who did not look like me. We learned very little about Algerian art, artists from South Africa or Latin America. It was almost exclusively about white artists, mostly men.

But that only became tangible after I had finished studying. Then I was confronted with reality. I couldn't find work in the sector, I had problems with my papers... The result was that for four years, I didn't make any art. During that period, I started to meet people who looked like me and who had gone through the same process. That was essential for my further development.

Your first artistic project came from an idea that you were not allowed to carry out at La Cambre.

Nasri: That's right, about an African ritual that consists of symbolically closing a woman's hand before marriage so that no premarital sexual intercourse would take place. After four years of artistic draught, this project, which denounces this symbolic violence, has reopened my eyes to the world and the state of women, in Tunisia, in the Arab world, but also in Belgium. Looking for a place to exhibit, I ended up in the loft of a photographer friend of mine, due to a lack of public spaces. He allowed me to invite other artists - like-minded people - and I was surprised by the turnout, which included racialised people and members of the LGBTQI+ community.

That small success made me see a new mission for myself: to make people who have been marginalised and too often hidden feel that they too are represented. Xeno~ was created in November 2019 and in March 2020, it became a non-profit organisation so that we would also have a status and weight in civil society.

A self-portrait by Brandon Gercara.

What exactly is your mission?

Nasri: We want to support women and non-binary people, promote non-binary artists and make them more visible, valorize artistic productions from the South, question patriarchal attitudes in the production and distribution of art and knowledge. Mainly through exhibitions, but we also make podcasts and in the future, we would like to participate in conferences. Finding the people we want to represent us remains one of our biggest challenges. That is why we try to be present in as many places as possible, in schools, at exhibitions...

Do other groups not feel threatened, maybe even a bit intimidated by your rather direct and frank approach?

Nasri: There is of course reluctance, first of all because people often think that we exclude men. It is true that we only exhibit women and people who identify as non-binary, but that does not take away the right of men to take more responsibility in the issues we raise, and to take account of their male privilege based on inequalities, rigid gender roles and prejudices, where a supposedly male characteristic is considered the norm.Others flinch when we use the term race or even think about it, but we must if we are to question the underlying systems. If we do not name everything, we will never understand anything, and the generations that follow will also not have representatives that resemble them. During and immediately after my studies at La Cambre, I didn't know what my artistic identity was, precisely because I didn't find anyone who looked like me.

It is true that we only exhibit women and people who identify as non-binary. But that does not take away the right of men to take more responsibility in the issues we raise

This is one of the themes of “Political Body II”, the exhibition you will curate in Pianofabriek.

Nasri: Tout à fait. The project explores more precisely how your body can also be a political weapon. It is your appearance, the first thing others see of you. We immediately notice whether someone is fat or black, whether they look like us or not, whether they are average people or people who do not follow the prevailing norms, such as fluid, non-binary or intersex people. The exhibition formulates questions that resonate both on a political and a personal level. Art becomes an object of intersectional and social struggle, a struggle that must be fought so that everyone can find their place in society without being judged.

So I have mainly chosen artists who emancipate in a social or political process. For example, Brandon Gercara is a non-binary activist in the queer milieu in Réunion. The poster for the exhibition is a (self-)portrait of the artist, who asked queer compatriots to share their experiences of trans identity and then staged those testimonies on stage. The result, like the work of Aay Liparoto, an American queer artist living in Belgium, shows great fragility. Leila Barkaoui, a young non-binary artist from Grenoble, works on eco- and decolonial feminism. Kamand Razavi from Iran explores the place of women in Iranian society. Laetitia Bica, a resident of Brussels from Liège, often reflects on ecology, but is also heavily built. For her, it was important to show the violence that is done to women and overweight people... It's true that at the moment I'm mainly taking care of other artists, but I promise to take a little break from Xeno~ soon to focus on my own work again. (Laughs)

Political Body II

Featuring Aay Liparoto, Brandon Gercara, Laetitia Bica, Leila Barkaoui en Kamand Razavi, and curated by Ichraf Nasri

7/5 > 13/6, Pianofabriek

Read more about: Expo , De Pianofabriek