What trickery of the mind has made that we have had to wait fifteen years for Lucy McKenzie to have her first solo show in Brussels, the city she has been calling home since 2006? With “Buildings in Belgium, Buildings in Oil, Buildings in Silk” at La Verrière, we can finally feast our eyes on the trompe l'oeils of the Glasgow-born artist who currently also has a retrospective at Tate Liverpool.

© Lucy McKenzie, Buildings in Belgium, Buildings in Oil, Buildings in Silk, 2021, detail, courtesy of the artist © Kristien Daem

Who is Lucy McKenzie?

Born in Glasgow in 1977

Studies at Duncan of Jor- danstone College of Art & Design in Dundee (1995-1999)

Moves to Brussels in 2006, where a year later she enrolls in the Institut Supérieur de Peinture de Bruxelles Van Der Kelen-Logelain, “the only school in the world to teach the traditional techniques of decorative painting” and is awarded the school’s gold medal

Together with Beca Lipscombe, runs fashion label Atelier E.B.

In 2017 her painted mural, part of Wiels’ “The Absent Museum” and an addition to Brussels’ Parcours BD, is inaugurated

2021-2022: has a retrospective at Tate Liverpool, curated by Kanal’s Kasia Redzisz, and has her first solo show in Brussels at La Verrière

“I wouldn’t want to be the artist that puts a cup in a room and have people thinking they haven’t read enough to fully grasp what they’re looking at. As an artist I always want to be generous. People take what they want from the work, but the gesture of giving is there on my part,” Lucy McKenzie says. She’s right. Her first solo show in Brussels – “Buildings in Belgium, Buildings in Oil, Buildings in Silk” – offers plenty to look at. Fourteen exquisite canvasses cover every inch of the walls of La Verrière, the Brussels art space of the Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, thereby creating mesmerizing tears in the fabric of daily life.

To any visitor, entering that enormous room at the back of the Hermès store on Boulevard de Waterloo will be an overwhelming experience. A confrontation, first of all, with the awe-inspiring skill the artist has invested in these hand-painted panels, that together make up one giant trompe l’oeil – including doorways, ventilators and woodwork – and with the perplexing beauty, the refined tones and colours in which bathe the figures and scenes that inhabit the paintings.

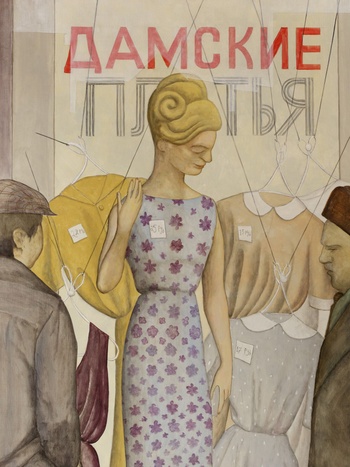

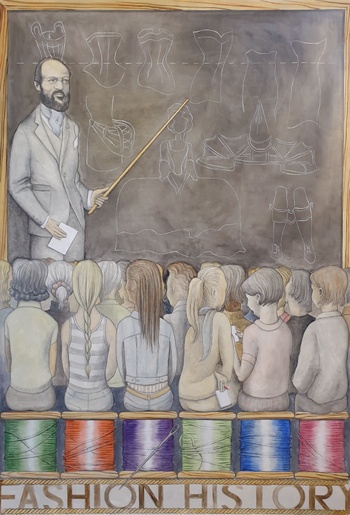

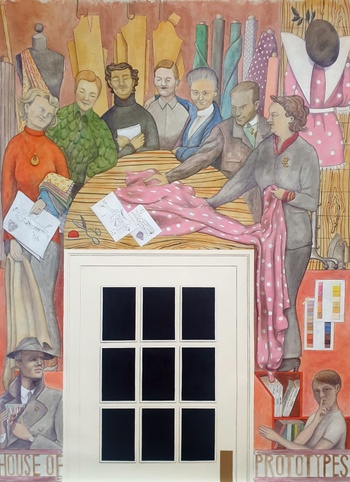

Once you catch your breath, you are drawn closer and start to notice that the panels don’t simply lift the space out of this dimension to drop it into another one, time travel has resolutely dropped them in the now. Various histories gently collide with each other and the present, the layers of time echoing within this one space, full of depth, nuance and complexity. Lucy McKenzie’s work gathers propaganda, theorists, architects, fashion designers, models, women in the kitchen, Soviet athletes and maps to assemble a space where ideology meets fashion, function dictates form, politics draw up aesthetics and theory distorts bodies. Where private solutions rethink fixed ideas, where men gaze and women are gazed upon (and vice versa), and where the collective gets personal. Where dressing up is dressing down, where things are in opposition and restored, torn apart and mended.

Trompe l’oeil is still really relevant today if you think about Instagram filters or VR or even the Metaverse, whatever that is going to be

These fictions delve deep into facts, in what has solidified as history, in what is revered and taught, made and remade, shown and seen, thought and made to think. They create an expanded, layered, diachronic space that is porous to a dizzying multitude of ideas. A very physical way of tackling the history of fashion and the ways it persists in our ideas of the self and the other, of seeing it with new eyes, nudging it towards new perspectives and reclaiming it.

DOUBLE AGENT

That is precisely the idea behind “Matters of Concern | Matières à panser”, curator Guillaume Désanges’ exhibition cycle at La Verrière, of which Lucy McKenzie’s show is the ninth and final part. The series “celebrates the resurgence of materiality in art as a critical alternative to the increasing dematerialisation of our dominant economic paradigm” and, through “referencing ‘other’ thinking and practice in Western art and society”, focuses on “modes of attention and curiosity that subtly undermine the accepted categories and disciplines of contemporary art.”

© Ivan Put

| Lucy McKenzie, dressed in her white coat, a remnant of her time at Van Der Kelen-Logelain: ”We always wore it. We were taught that it was a sign of our self-respect.”

“It was a discussion with Guillaume that was the starting point for this work,” Lucy McKenzie says. “During a studio visit he had seen a work of mine inspired by Mexican murals, this overwhelming complete carnival of images and information. Our conversation ventured into the topic of the ambiguous relationship the historic left, and maybe even the contemporary left, has with labour and how it is depicted on those murals. They love to celebrate it, but it’s always with a bit of distance – sometimes fetishizing it, sometimes idealizing it. The same goes for fashion: the left historically has a problem with fashion, because it is individualistic, it’s connected to capitalism, planned obsolescence, but nevertheless people all want to look and feel good and be different. So in the Soviet Union for example, you had this very complicated ecosystem of fashion, where it could not be denied but it had to be ideologically correct. Amidst all this friction I thought of using those big socialist-style murals and have them deal with different aspects of fashion. As two aesthetics that have always been in a kind of opposition. And then by doing the show in this particular context, with the store that has a history of its own, I thought I could be a double agent.”

You work through appropriation. It's an approach that sort of goes against the idea we have of the artist as a genius who creates from a blank page.

Lucy McKenzie: I consider myself a life-long learner. I have always been a bit obsessed by how things get made. And once I would find out, I would try and make it myself. Of course, it wouldn’t look like the thing I was trying to make at all, but this other thing would have its own quality. And that’s my take on a lot of things: I go out to see a fashion boutique or art exhibition and think: “What would we do different?”

© Lucy McKenzie, Buildings in Belgium, Buildings in Oil, Buildings in Silk, 2021, detail, courtesy of the artist © Kristien Daem

You know, one of my favourite art forms is renaissance paintings that have been copied in the 1930s. It helps you learn about certain beauty ideals or things that we take for granted or just don’t notice in contemporary life. By working with forms that are a little bit out of date, out of fashion or out of favour, you can see that these things one day were very fashionable. Just look at Brussels’ relationship with art nouveau. So it becomes obvious that this kind of sine wave of taste is connected to ideology, gender politics and so on.

It helps you find the structures behind it?

McKenzie: We’re in a wonderful moment now of looking back at the grand narratives of history and think of all the people who have been excluded, of all the things that were disregarded because they were ill considered. The idea that you can change the world by looking at it afresh, is very contemporary, even if it is not seduced by contemporary technology. In my view, trompe l’oeil is still really relevant today if you think about Instagram filters or VR or even the Metaverse, whatever that is going to be.

What was it that attracted you to trompe l'oeil?

McKenzie: So many things. First of all: this connection to the uncanny, to illusion, to this idea of being tricked. You set up a power relationship between you and the viewer that is interesting. And part of me is always tapping into this kind of primal, original connection with art, to the pop-up books and doll’s houses I loved as a child. But fundamentally: I grew up in an era where I saw so many artists discussing political engagement, in a very earnest way, but in my mind they were not engaged with politics, they were engaged with aesthetics with a lot of rhetoric. In my mind it felt more honest to say: “This is trompe l’oeil.” Rather than try and say it was something else.

NERDY TEACHER'S PET

“I have a lot of respect and love for genre fiction, whether that is crime fiction or romance writing, mediums that use tricks,” Lucy McKenzie says. “I’ve read enough great writers to know that within these instantly satisfying formulas, you can still be avant-garde or radical. It kind of goes against this idea of seduction being dangerous, especially when you like to hide in cynicism and take up the position of ‘It’s not good’ and ‘I told you so’. But I think it’s riskier to depart from a more positive idea.”

© Lucy McKenzie, Buildings in Belgium, Buildings in Oil, Buildings in Silk, 2021, detail, courtesy of the artist © Kristien Daem

Enter the trompe l’oeil, a skill she perfected in Brussels, the city the Glasgow-born artist has been calling home for fifteen years now. “I moved in 2006,” Lucy McKenzie nods. “I first came to explore the city in 2004, because it seemed that many things I was interested in and was already incorporating in my research had a relationship with Brussels or Belgium, whether that was comic books or design, art nouveau, certain kinds of music and fashion and textiles and so on. So I came for three months and I really liked it. When a few years later I decided to leave my hometown, as a strategy of deferment, of taking some distance, I had these good memories of Brussels and so I decided to return.”

What is keeping you here?

McKenzie: I have a great studio in this old building I found, not long after deciding to settle here. So first and foremost, it is this great working situation that is keeping me in Brussels. But over the years I have discovered more and more about Belgium. Some things I don’t like or don’t feel strongly about – like its conceptual art history – but other things I really like – like the many cultural hybrids and collisions – and some I find a real connection to. Like the historic carnival culture, the Decap organs, or the Toone puppet theatre…all things that come up from mass culture, and that link Belgium to Scotland rather than to France where grand narratives shape the history of art.

In 2007 you enrolled in the Institut Supérieur de Peinture de Bruxelles Van Der Kelen-Logelain, “the only school in the world to teach the traditional techniques of decorative painting.” In all honesty, I had never heard of it.

McKenzie: It’s an incredible school! Really, it should be UNESCO protected. When I studied there, they were celebrating their 125th anniversary. It has always been in the hands of the same family. The daughter of the woman who taught me is currently taking over. We were 35 students at the time, and I have heard the numbers are down a bit and it costs a bit more, but those six months have had a lasting influence on me.

The historic carnival culture, the Decap organs, or the Toone puppet theatre... They are all things that come up from mass culture and that link Belgium to Scotland, where I was grew up, rather than to France, where grand narratives shape the history of art

How did you come by the school?

McKenzie: I had been making fake wood and fake marble for a while, but I could tell that I was up against the limits of what I could learn myself. Just like this great coincidence I saw this article about the school in a coffee-table book about Brussels interiors and I just Googled it and signed up. It was hard work for a lazy artist. (Laughs) You basically work seven days a week, you can’t do anything else, and the contrast with a normal art school is huge. Suddenly you’re in a situation where there’s no place to hide, where “But it’s supposed to look bad” is no excuse. I found it refreshing to work to someone else’s criteria: “It’s wrong, do it again! It’s not enough, do more!”

You're no longer at the centre of your own world?

McKenzie: Exactly. You do it as an individual but because it is so difficult you have to have a good relationship with your fellow students. You bond together, because you’re all kind of traumatized from the experience. When a few years later I started teaching in Germany myself, I knew that I wanted to, in a way, base my teaching strategy on the things I had learned there. Because it turns this group of individuals who are all trying to be the best, with one or two students dominating the group, into something else. Because you’re teaching these old techniques, some of the students who maybe weren’t used to getting attention, suddenly excelled and got a different role. It disrupts the paradynamics of the group. Some of the other students pushed back because they didn’t like to be told what to do. But I knew I was there to learn something so precious, so I gave up all my ego. And I loved it. I mean, I would go back instantly, like this nerdy teacher’s pet.

© Lucy McKenzie, Buildings in Belgium, Buildings in Oil, Buildings in Silk, 2021, detail, courtesy of the artist © Kristien Daem

Did your view of your position as an artist change?

McKenzie: Sort of. I definitely found it interesting that you were constantly being taught that you as a painter should be paid the same as say a plumber or an electrician. You know, we always wore this white coat. We were taught that it was a sign of our self-respect, that it showed that we were working and taking it seriously. And I just kind of connected to that. Not that I see myself as a manual labourer, I’m not at all. The value of art isn’t only connected to labour, hours and skill, art can be about gestures and immaterial labour. And I do tend to play with that, go and follow in one direction to then undermine it and go somewhere else – make a trompe l’oeil, hear talk about how valuable people consider all this time spent on it, and then next time show a photocopy. “This is not what you thought it was!” But there is just something about that idea of self-respect that spoke to me. It’s considered old-fashioned nowadays, but I think we have to reclaim it a bit.

CRAZY CAT LADY

It is this in-between status that makes Lucy McKenzie such an irresistible artist. A lot converges in the sympathetic Scotswoman: high and low culture, contemporary practices and forgotten crafts, the personal and the collective, a highly independent mind and a generous practice, local histories and grand narratives, trickery and seriousness, form and function, art and the everyday, criticism and celebration. A highly idiosyncratic mix that is at the same time strongly anchored in reality and the everyday.

From very young I was always very sure that what I found interesting was legitimate. The idea that I couldn’t paint cats in dresses never crossed my mind

“As an artist you can be a bit in an ivory tower,” Lucy McKenzie explains, “where you don’t do this and you don’t do that. With fashion, already a commercial sphere, you’re obliged to compromise or be in situations you’re not 100% sure about. I think that’s an interesting position to be in.” Which is why Lucy McKenzie, together with Beca Lipscombe and Bernie Reid, founded Atelier E.B. – E for Edinburgh, B for Brussels – in 2007. “Since 2011, the collective just became two people, me and my ‘work wife’, designer Beca Lipscombe. When we, as a duo, got invited to research the Scottish textile industry and see what clothes you can make in Scotland, we spontaneously decided to try and make some ourselves. So we did and people started asking: ‘Can we buy them?’ That’s how we became a fashion label. But making very small amounts with as much ethical and local production as possible. It’s one part of a bigger practice revolving around art and design, a quiet way to make avant-garde fashion and to honour local histories and crafts.”

In addition to your fashion label, you also run a music label for friends and curate exhibitions. You paint, make installations and architectural models. Was that do-it-all spirit already present when you were a child?

McKenzie: No, I was just drawing all the time. All sorts of things, cats in dresses, Tintin as a girl… From a very young age, I already knew that I was going to be a fashion designer or an artist. Now I’m both. Our new fashion collection, which will be partly exhibited in a vitrine in the show, and presented in a showroom in my studio, is tapping into exactly that period when I was drawing as a child. It’s a mix of things connected to that time, but then we got the clothes made in Belgian lace to also connect them to the present.

© Lucy McKenzie, Buildings in Belgium, Buildings in Oil, Buildings in Silk, 2021, detail, courtesy of the artist © Kristien Daem

You had me at “cats”! I noticed another one in the show. Is that your mode of rebellion, to allow for everything and anything in your work?

McKenzie: I don’t really see it as rebellion – more so, every time I have tried to do something rebellious, like stop my career for six months to go back to school and study decorative painting, the art world loves it. The strategy of refusal just doesn’t work for me. (Laughs) I’m just very pig-headed, I think, I do what I want. From very young I was always very sure that what I found interesting was legitimate. I never felt that I should be making art about this or that just because it was serious. Maybe with the support of my family, the idea that I couldn’t paint cats in dresses never crossed my mind. And then seeing that when you did all those things, that it could be quite antagonistic, in a way that felt artistically productive, like I was taking some risks. Because I was emphatically standing up for things that other people found ephemeral.

You know, I think I have this parasite called toxoplasmosis. I’m sure I have it. You get it from cats, and it has two symptoms: it makes you take risks and it makes you love cats. I have had cats since I was about seven, so I blame them. It's the worm in my brain that is telling me to paint cats. (Laughs)

LUCY MCKENZIE: BUILDINGS IN BELGIUM, BUIL- DINGS IN OIL, BUILDINGS IN SILK

21/1 > 26/3, La Verrière, fondationdentreprisehermes.org

PRESENTATION ATELIER E.B.’S DASH PEOPLE COLLECTION

21 & 22/1, 12 > 18.00, Slachthuislaan 16 boulevard de l’Abattoir, Instagram: @atelier_e.b

Read more about: Expo , Lucy McKenzie , La Verrière , Atelier E.B.