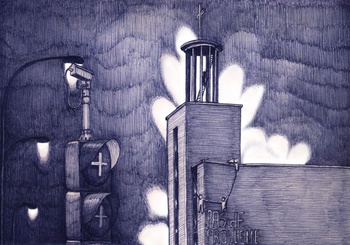

Blood-red and steel-blue. With a series of ballpoint pens in two colours, Mikkel Ørsted Sauzet cuts a conscience onto paper. The French-Danish comic book artist allies these simple means to a sincere concern for the world both past and present, a bittersweet sharpness of mind, and “a big, fat, local accent”. “That’s the privilege of making alternative comics that don’t earn you anything: you can do as you wish.”

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.