With Maus, Art Spiegelman expanded the visual and narrative possibilities of what a comic strip could be, all the while depicting the burning spirit of Jewish identity. On the occasion of the exhibition “Superheroes Never Die” at the Jewish Museum, we spoke to the comics hero about the Jewish roots of the comics scene, super powers, and the battle with the Orange Avenger occupying the White House.

© Art Spiegelman

| Art Spiegelman and Maus

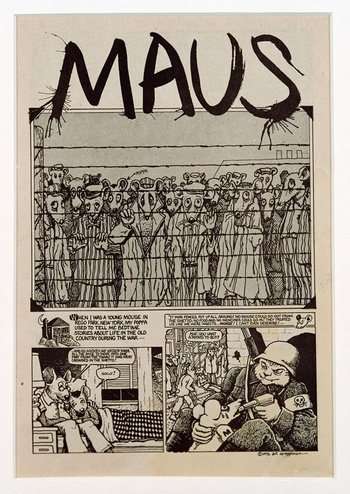

About the article that you are writing about ‘Superheroes Never Die. Comics and Jewish Memories’, well, I have good news: you can call him.” Aaargh! Art “%?&*@#!” Spiegelman! A short circuit in the brain. Just like how sparks started to fly in my stubborn, culturally still terribly malnourished young head when I first laid my eyes on Maus. Was it because of the incredibly painful details from the inevitably heartbreaking story that Art Spiegelman documented between 1978 and 1991 based on the stories of his father, a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor? Was it the unusual way in which that historical core was presented: in a comic strip in which Jews appeared as mice and the Nazis were depicted as cats? Or was it the uncompromising way in which the book’s creator also dissected himself, depicting his own struggle as a post-war cartoonist with the tragic legacy of his parents and the burning spirit of Jewish identity? With wry and yet inspiring humour, poignancy and disbelief, pain in the soul and lost love, awe and resistance, patient attention to and impatient rebellion against a heritage that is forever linked to Great History.

It was undoubtedly a mix of all these things that made Art Spiegelman’s brilliant story, which is as personal as it is political, blow up the barriers in my head, as he mercilessly rummaged around in the memory of both the Jewish community and his own inner world. I was not alone. Maus won a Harvey Award, an Eisner Award, prizes at the Angoulême International Comics Festival and it was the first comic book ever to win a Pulitzer. The narrative and visual complexity of the book continues to be praised and studied, Maus is still referred to as a book that redefined the comic book medium, and the book continues to burrow itself into the heads of people who identify with the confrontation with the incomprehensible, with the attempts to escape from the inescapable, with small, wildly struggling arms that want to grasp a shadow that is far too big.

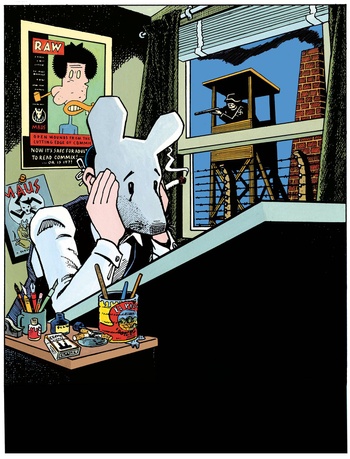

© Art Spiegelman

| In 1972, Art Spiegelman included an early chapter of Maus in Funny Animals #1. It never made it to the graphic novel that eventually won him the Pulitzer Prize

It was only later that I discovered that Art Spiegelman – the boy who started drawing comics in 1960, at the age of twelve, who half a decade later went to work as an illustrator for Topps Chewing Gum, Inc., and who started selling his own first underground comix on street corners – was also, along with his wife Françoise Mouly, the founder of RAW. Between 1980 and 1991, that “graphix magazine” offered a platform to the greatest iconoclasts on earth (and beyond), or at least to my underground-addicted eyes: Charles Burns, Ever Meulen, Kamagurka and Herr Seele, Chris Ware, Richard McGuire, Alan Moore, Robert Crumb, Lorenzo Mattotti, Joost Swarte, Gary Panther, and many more. And it was that same Art Spiegelman who turned himself inside out in Breakdowns, spent years drawing the covers of The New Yorker, and who, after the 9/11 attacks, released the sublime, extra-terrestrially multifaceted In the Shadow of No Towers on a hopelessly divided world, and who, as an editor, drew my attention to the absolute gems of people like Lynd Ward. That’s the man…that I’m supposed to call…aaargh!

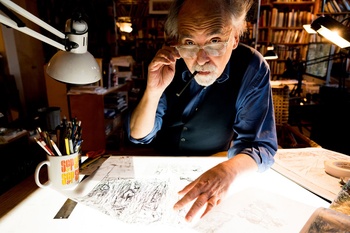

MOSES ON A ROCKET SHIP

“I gotta say that I ultimately consider myself an American cartoonist more than a Jewish American,” says Art Spiegelman when I call him at home in New York for an exchange about the Jewish roots of the comics scene. I repress the urge to talk his ear off about Maus and Co. in favour of a broader story as suggested by “Superheroes Never Die”. The exhibition at the Jewish Museum interweaves a century of comics with the promise that the medium, and especially the superhero genre, held for Jewish artists and the influence they had on a rapidly developing scene.

“I am about as Jewish as it gets,” Art Spiegelman says, “if you can avoid the religious aspect of Judaism. Culturally I relate to the diaspora tradition. But it’s only over the years that it became clear to me how many cartoonists actually were Jewish. I would see Li’l Abner, one of the great comic strips of the late 1930s and 1940s, by Al Capp. When I found out that his name was actually Alfred Caplin, I went: ‘Oh that’s cool!’ and at twelve years old, when I was doing my first little comic strips and was just starting to see how to use Indian ink and pens, I signed a couple of them: ‘Art Speg’. As if that was as cool a name as Capp. (Laughs) That lasted about a month maybe, at the most.”

© Phil Penman

| Art Spiegelman

In the 1930s, such double identities were a way for Jewish comic strip artists to integrate in a society that would otherwise have rejected them. As the children of a first generation of Jewish immigrants who moved to New York to escape the pogroms and repression to which they were subjected in Europe, it helped them to climb the social ladder. “Jews were not especially welcome in those early days,” Art Spiegelman says about that. “They couldn’t go to lots of hotels, they couldn’t find apartments to rent… It wasn’t a desirable group. And they – we – were not seen as very classy. So careers for an artist who was Jewish were very circumscribed. They weren’t invited into the higher precincts of culture, couldn’t get jobs in advertising agencies or illustration of the more refined kind, and they ended up in comics sweatshops.”

It was a printing salesman, Maxwell Gaines, who invented the comic book format by accident, when he started reprinting newspaper comic strips, packaging them together, and selling them for 10 cents a piece. “The big bang came when Gaines bought the first pages that two Jewish kids from Cleveland, Ohio, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, had made of a superhero who could protect truth, justice, and ‘the American way’.” It was 1938, and Superman was born, or rather appeared, like Moses in the bulrushes, when he was sent to Earth on board a rocket ship.

“It’s not a coincidence that the superhero myth came during the Great Depression leading up to World War II,” says Art Spiegelman. “I mean, the myth underneath these superhero stories was an important one, it was a core dream that was passed into.” A dream of Jewish kids, connected to identity, emancipation, and the protective shell of the imagination in a very precise social and political context of a world in crisis. “In the beginnings of Superman, Siegel and Shuster had a kind of liberal, Jewish interest in the New Deal (president Roosevelt’s response to the Great Depression, ks). So their superhero fought for the unions and against Nazis and corrupt city bosses – those were the villains in the beginning. Superhero comics soon became a genre, as soon as it proved to be successful, and an industry grew up around it.” One in which DC and Marvel were able to grow into the two giants they are these days.

“And that lead into not just Superman and Batman, but also the Green Hornet, and – oh, I don’t know – the ‘Green Tornado’, the ‘Yellow Jacket’, and so on and so on. (Laughs) It was a big deal.” By 1941 you had the red, white and blue, Joe Simon and Jack Kirby’s Captain America, punching Nazis and even coming face to face with Hitler. It was a way to encourage the United States to get involved in the war that was ravaging Europe.

I ultimately consider myself a cartoonist American more than a Jewish American

CRACKING THE CODE

“I read superheroes,” says Art Spiegelman, “they were what was around. They’re part of every kid of my generation’s library of reading material. So even as late as 1972, I could tell you who was drawing Conan or Kull the Conqueror… But those fantasies were not my fantasies. The branch of the family tree that got me was things between Donald Duck and the MAD comics, before it became a magazine even. That’s the stuff that really made my heart beat faster.”

“Also, I’m a post-war kid, so by the time I grew up, other genres had taken over: crime comics, love comics, horror comics... In the mid-1950s, those led to a kind of moral panic about comic books. My real comic book reading years came after that panic that had led to the very draconian Comics Code of America, in 1954. Comics wouldn’t get distributed on newsstands without getting the seal of approval, there were senate hearings (investigating the connection between comics and juvenile delinquency, ks), and comic book burnings... The school I went to in college, that town had one of the big burnings. I have a photo of that that I keep around. The industry was decimated and had to start from scratch. It was in that context that I discovered Superman, when his biggest problem was how to make sure Lois Lane didn’t know who he was. It wasn’t world epic battles anymore.”

“When discovering MAD and the other things at about ten or eleven,” Art Spiegelman continues, “that created my calling, that created the reason that I wanted to be a cartoonist. Because it was very subversive, questioning adult authority and showing you what’s really happening.” Art Spiegelman’s father unknowingly contributed to that. “He was shocked that I would spend my allowance money on comic books, and he had a place where he could get them cheaper, near the diamond dealers’ district that he worked in. He would just scoop up a bunch of comic books and bring them home. He didn’t know he was bringing me the horror comics that created juvenile delinquency and the really good semipornographic comic books from the 1940s. (Laughs) That’s how I discovered the forbidden fruit.”

Art spiegelman

SCALPING THE ORANGE SKULL

Fast forward to last summer. Art Spiegelman was commissioned to write an essay for the collection Marvel: The Golden Age 1939-1949. A reference to a certain Orange Skull – a nod to Red Skull, the archenemy of Captain America – made headlines. “In today’s all too real world, Captain America’s most nefarious villain, the Red Skull, is alive on screen and an Orange Skull haunts America,” Art Spiegelman wrote. “The Folio Society invited me, but what they didn’t tell me was that Marvel was a co-publisher,” he explains. “All of a sudden they asked me not to publish the reference to an Orange Skull. When they confessed that Marvel was the co-publisher and I found out that Isaac Perlmutter, who was in charge of all Marvel publishing, toys, and licensing, and for a while also the head of Marvel Movies, was part of Trump’s kitchen cabinet that meets at Mar-a-Lago, it all added up. He’s a friend of Trump’s, one of his biggest donors, and clearly his fingerprints are on this book. So I pulled the essay. But he turned out to have done me a giant favour. What would have been the little grey dots on the front of a book with lavish reprints of Marvel comics, was published first in The Guardian and then about ten other newspapers around the world. So I just couldn’t have imagined a better result from such an essay.”

There is something basically fascist about the idea of a superhero. There’s something creepy about putting all of your faith in vigilantes to protect you

This is an illustration of where “Superheroes Never Die” got the idea to update what had started in 2007 as an exhibition about Jewish identity organized by the Jewish museums in Paris and Amsterdam. The times of crisis have returned, as have the caped and masked warriors of justice. Like Art Spiegelman wrote in his essay: “Armageddon seems somehow plausible and we’re all turned into helpless children scared of forces grander than we can imagine, looking for respite and answers in superheroes flying across screens in our chapel of dreams.”

“That said,” he says on the phone, “one of my problems with those superhero comic books, even if they’re by Jewish artists and if they emerged as a response to the rise of the fascist threat in the world, is that there is something basically fascist about the idea of a superhero. There’s something creepy about putting all of your faith in vigilantes to protect you. It has something of the powerful and the sheep built into the idea of it, that makes me suspicious.”

“Then again, I don’t have any major problem with this renewed focus on superheroes these days. I have a major problem with America, with the world. When I grew up there was a phrase: ‘Never again.’ Well, the statute of limitations ran out on that. There’s a fascination with fascism again, and not just in America. It is terrifying. You know, I haven’t been out and talking about Maus very much for years. I never made it to make the world a better place or teach anybody anything. But recently I agreed to do it again, because I now see in my dotage that there’s reasons for people to read Maus except for it being narratively sophisticated and dealing with history and the transmission of memory bladibladibla. So if that’s what they’re asking me to come out and talk about, well, I’ll answer.”

Read more about: Brussel , Expo , Art Spiegelman , Maus , Jewish Museum

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.