What do an inflamed nasal canal, Beyoncé, linocuts, French fries, euthanasia, Brussels’s underground scene, and Gertrude Stein have in common? Flem, the debut graphic novel that Rebecca Rosen has picked from her nose and which is being showcased at Cultures Maison.

© Rebecca Rosen

Who's Rebecca Rosen?

- Who? A Canadian-born illustrator and comics artist.

- From Canada? Yes, it’s where she was born, bitten by the comics bug, and where she eventually ended up as part of the production team at Drawn & Quarterly, an internationally renowned comics publisher.

- In Brussels now? After picking up silk-screening and noticing how liberating it felt to get her hands in the ink, she did an internship with Le Dernier Cri. That’s where she met Quentin Pillot, and together they started their own printing studio L’appât.

- L’appât? A true Brussels treasure, surrounding their books and posters with all the care they could possibly want.

- Flem? Her debut, published at Conundrum. Yes, we needed a Canadian artist to give Brussels the layered, surreal, and loving graphic novel it deserves.

With Flem, the Canadian-born, Brussels-based artist Rebecca Rosen has unleashed a layered, colourful, and addictive piece of hallucinogenic comic art on the world. It is a book that deeply penetrates your body and settles in your bloodstream like a clot. It gives you a beating, moves and yet disturbs you. It is the kind of graphic novel that has been central to the past seven editions of Cultures Maison, the pagan feast for contemporary comic strips, and which they consider their mission: devoting attention to the valuable undercurrent, to all the ground-breaking initiatives in the comic strip scene, from small but beautiful publishing initiatives to graphic novels that elevate the medium to new heights.

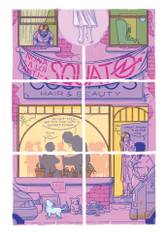

In Flem, Rebecca Rosen delves into the undercurrent and shows a side of Brussels that would probable not feature in the big campaigns of Visit Brussels. The revolution is being planned in a squat, devils are being exorcized in Barlok, and at Sainctelette, a tormented soul is being puked out of a body… In Flem, Brussels engulfs you as in a murky dream. “In Montreal, it is nearly impossible to open and sustain an underground venue,” Rebecca Rosen tells us. “Rents are too high and there just isn’t the same attitude of tolerance for unlicensed spaces. It’s easier for people here to create the kinds of temporary autonomous spaces where underground culture can flourish.”

© Heleen Rodiers

At L’appât, the printing studio and artist residence in Vorst/Forest, Rebecca Rosen and Quentin Pillot occupy a space with a direct connection to that sweltering underground. It is a space that will soon blend with the Brussels portal to dark and perverse worlds, Sterput, and which resulted from an equally overwhelming internship at Pakito Bolino, godfather of 25-year-long death rattle, publishing platform, screen-printing studio, and residence space Le Dernier Cri at Marseille. A place where unbridled freedom and graphic ecstasy go hand in hand, and which inspired Rebecca Rosen and Quentin Pillot to hook up and start a studio together – first in Montreal and after a year in Brussels.

“I used to live in a squat myself in Marseille. My personality didn’t totally mesh, but we have a lot of friends who live(d) in squats here. I think it’s important to have that kind of culture of resistance. Grass-roots activism is a necessary corrective in a system in which the interests of corporations and wealthy individuals guide decision-making.”

CRAZY IN LOVE

In Flem, a squat represents a way out for the main character Julia, an art school student who is at war with the expectations of the world, but also and especially with herself. An inflamed nasal canal keeps her inside, where she devotes herself to linocuts and very lively memories of her mother, who committed euthanasia. A bloody performance by a radical feminist group, to the tones of Beyoncé’s “Crazy in Love”, leads her into the activist milieu.

In Brussels you have a lot of temporary autonomous spaces where underground culture can flourish. It’s important to have that kind of culture of resistance

You were also a member of such a group?

Rebecca Rosen: When I came to Brussels, there was a group that had been formed out of Femen, called the LilithS. I don’t know if you remember, but four years ago there was this group that threw French fries at Charles Michel…that was us. And during the siege of Gaza we poured a few hundred litres of red paint at Liège airport because weapons were transiting through that airport. We did a couple of actions, but our group sort of petered out because people had different interests.

What made you join the LilithS?

Rosen: I agreed with their perspective on the issues they were addressing at the time, and shared their feeling of urgency. And I was new in Brussels and looking for friends and a community. I was very lucky to meet such an extraordinary group of women! I wasn’t always totally comfortable with their methods, but confronting my discomfort – about, for example, making a commotion in public – was an important learning experience for me.

Swallow me whole

“The system is designed to keep us trapped in our individual struggles so that the only thing that can rise up is the rent!” we read in Flem. “But when we come together in communities outside the system we’re strong enough to fight back! Loud enough to be heard!”

Nevertheless, the focus of Flem is Julia’s individual struggle, which is irreconcilable with the political struggle. “Exactly,” Rebecca Rosen says. “I was interested in exploring what happens at the conjunction of personal struggle and political struggle. Sometimes people join these radical groups in order to not have to deal with their personal issues. That can be difficult for the individual, because then they’re subsuming a lot of things, but also on the collective, which is not set up to deal with individual struggles.”

It swallows you whole?

Rosen: When it comes to that kind of action… It is like the American activist Mario Savio said in his famous “machine speech” in 1964: “You’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels…upon the levers, upon all the apparatus.” That is what street activism, direct action is about. It is very physical and you’re very invested. The whole person is invested. I think that makes it harder to separate the political and the personal life. There’s sort of a self-abnegation, a denial of yourself that can happen when you get involved in a political group.

What sparked the idea for Flem?

Rosen: I saw that happening a lot around me, in the political groups that I was involved in: people’s personal struggles going unchecked. I think it’s pretty common. This summer…one of the founders of Femen and a brilliant artist, Oksana Shachko, who lived in Paris, killed herself in a squat. Her early death is a great loss for both the worlds of art and activism.

© Rebecca Rosen

UNDER THE SKIN

“You keep digging and digging with your little tools but you’re not getting anywhere. I mean…you aren’t getting any deeper,” Julia’s art school professor says about her linocuts. You couldn’t say that about Flem, which clearly got under its creator’s skin. “I think writing about euthanasia, mental illness, depression, or psychosis, is always going to be delicate. These issues have to be approached with a certain sensitivity, and that’s not the way that I work. [Laughs] It only works if you can bring some part of your personal experience to the writing.”

Wat was that personal experience?

Rosen: When I first moved to Brussels, I went through a period of depression during which I acted in ways that were objectively self-destructive and pushed people away, not unlike Julia. Luckily, I was able to pull through it with the support of my wonderful partner – shout-out to Quentin! I’ve also been very close to people who are not neuro-typical and/or dealing with longer-term mental instability; I’ve watched helplessly as they go through periods of psychosis, addiction, suicidal ideation – the whole roller-coaster.

Rebecca Rosen has managed to process that emotional onion in a story that shows these layers openly. Flem looks delicious. It is wonderfully fluid in form, colour, and as light as it is complex thanks to the way that Julia’s linocuts interrupt the story and Julia’s inner life is presented as a kind of augmented reality. “For me the whole book sort of takes place in Julia’s mind,” Rebecca Rosen tells us. So she shows what that would look like: somewhat surreal, but also the way we see the world, always coloured, metamorphosing. “When I started writing Flem, I was reading a lot of the Left Bank women, early 20th century modernist female writers living in Paris, like Djuna Barnes, Jean Rhys, and Gertrude Stein. They’re very much about experiential writing, so you’re in the skin and the mind of the character.”

Combine this very refreshing perspective with the unique way in which Rebecca Rosen’s printing and silk-screening experience at L’appât affected her, and the result is a maelstrom of a graphic novel. “In silk-screening, you print one colour at a time, and that’s sort of how I built up the images. I actually drew each colour layer individually and then assembled them on the computer. Kind of crazy, I know, and super time-consuming. But I think it gave some nice textures.”

“And I think for me, building up the colours layer by layer, there was sort of a synchronicity with building up the story scene by scene. I was writing it as I went along and so sometimes I got to a halfway point and I thought: ‘I don’t know where this is going!’”

Into the underground. Under the skin...

> Cultures Maison. 21 > 23/9, LaVallée

Read more about: Events & Festivals , Expo , comic , Festival

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.