What festival would screen 25 films about the recording of death on film and the human urge to watch it? Offscreen of course, our favourite beacon of light in the deepest recesses of cinema. Looking death in the face is the speciality of David Kerekes, the author of the standard work Killing for Culture: From Edison to Isis.

© Gilles Vranckx

This year, Offscreen is dancing with death. There is also a thematic strand about films and videogames, a tribute to (s)exploitation pioneer Roberta Findlay, and a selection of new films that will transport lovers of unconventional and non-conformist cinema to cloud nine. But the most ambitious thematic section of the twelfth edition is a programme around the recording of death and violence on film. Offscreen was inspired by Killing for Culture: From Edison to Isis, a standard work by the Brit David Kerekes. The pitch: unlike images of sex, which were clandestine and screened only in private, images of death were made public from the onset of cinema. This book is about those images and their impact on society. Kerekes is one of the guest speakers at the conference Death on Film, but we couldn’t wait that long to hear what he has to say.

How does somebody become an authority on death on screen?

DAVID KEREKES: By coincidence, really. In the early 1990s, David Slater (co-author of Killing for Culture, nr) and I explored the things that fascinated us. We primarily wrote for ourselves because we were still quite inexperienced. Unplanned, the result was a book about death on film. Killing for Culture soon became a kind of standard work and people have been speaking to us about the subject ever since.

A few years ago, we added several more chapters to the book. There was barely an internet yet when we wrote the book, so we had a lot of catching up to do.

Offscreen is screening Faces of Death, a forty-year-old collage of horrific scenes of dying people, some of which were staged while some were not. The video was a scandalous success and there were dozens of sequels and imitations. In the 1980s, the playground was full of the wildest stories about Faces of Death.

KEREKES: Faces of Death had such a good reputation that young people felt obligated to have seen it. It was part of coming of age. That reputation persists even now. It has been absorbed into popular culture. It was referenced in The Sopranos, for example. In the States, somebody apparently got into trouble because he showed Faces of Death in class. It traumatized a number of students.

© Mark Berry

But surely we’re used to seeing far worse things nowadays? Including genuine footage of death: the execution videos by IS, newsreels of executed leaders and rappers, smartphone recordings that show the Charlie Hebdo murderers killing a police officer.

KEREKES: You can link Faces of Death with those internet clips. They are a progression of the film. Films like Faces of Death and Mondo cane seem to anticipate this culture where we can see and access these images of death. The difference is that we’ve lost control over what we see. Faces of Death was a video. You could choose to watch it or not. On social media, we are often caught out by surprise. We can logon to Facebook and see filmed atrocities before we even know. That happened to me recently. The atrocities hadn’t been posted by gore hounds but by people who genuinely thought they were tragic and horrible. My point is that I had no choice. I had already seen the video before I had decided whether or not I really wanted to see it.

Do snuff films, films in which people get murdered, exist to pleasure the buyer/watcher? In the 1990s, I learned at university that snuff films are an urban legend.

KEREKES: Did you say in the 1990s? That was probably accurate back then. We researched that question for two years for Killing for Culture. That wasn’t easy because there was no internet. Whenever anybody claimed to have seen a snuff film, it turned out to be Faces of Death. Which was not a snuff film. We constantly drew a blank. So we were also inclined to say: snuff movies are an urban legend. And yet everyone knows what a snuff movie is. So where does that concept come from?

Today, I am not so sure. As you know, people regularly murder other people on camera. Just think of the IS videos or those of certain drug cartels. But those recorded murders serve propaganda purposes; they are not made for commercial gain.

I have seen enough shockumentaries to last a lifetime

Is that difference important?

KEREKES: Not to the victim, no. I don’t want to argue semantics – at the end of the day people are dead – but I do think there is a genuine difference. The legend of the snuff film is still a legend. I’m not so stupid to say it doesn’t exist. I just don’t know. I’ve never seen a snuff film made for commercial gain and I’m glad I haven’t.

But there are people who pretend to have made snuff films. Is the film Snuff not a good example of that?

KEREKES: Snuff is pretty much where the modern mythology of the snuff film originates, though the concept of snuffing somebody out has existed for much longer.

Distributor and producer Allan Shackleton had shot the end of a low-budget horror film that was never finished. At the end of the film, one of the actresses was apparently murdered by the crew. Shackleton was a marketing genius. He promoted Snuff by claiming that somebody had genuinely been killed during the shoot. He erased the credits so that it would look more sinister, refused to answer questions from journalists who wanted to know if the murder was real. He himself even stimulated animosity and anger against the film by calling feminists, for example. FBI agents appeared in the cinemas. Anybody who had seen Snuff knew that it was not a real snuff film, but most people refused to see it and continued to decry it. That, in a nutshell, is the history of the film Snuff and of the urban legend.

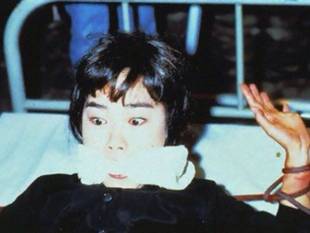

That reminds me of the story of Charlie Sheen, the actor from Platoon and Wall Street who asked the FBI to investigate whether Guinea Pig was a snuff film.

KEREKES: Yes, but there is still a difference. Guinea Pig is the artistic experiment of a Japanese manga artist. As far as I know, the artist never once suggested that it was a snuff film. The film consists of one long murder scene, and Charlie Sheen was not the only person to be so overwhelmed by the realism to raise the alarm.

Are there other taboos?

KEREKES: A lot depends on the packaging. People watch brain surgery on television, but they don’t make any kind of connection with exploitation cinema because they imbue the images with a different value. On the other hand, Faces of Death intentionally courted controversy. Crash, David Cronenberg’s adaptation of the book by J.G. Ballard, was deeply controversial when it was released. But that controversy was created by the media. It was an example of controversy by proxy. Nobody had seen Crash and yet somehow it had become a cause célèbre. It’s not a controversial film in and of itself, it was made controversial by the media. And Crash is actually quite a boring film.

The same cannot be said of Man Bites Dog.

KEREKES: Isn’t that the Belgian film about a camera crew that follows a serial killer? That was a controversial film and so ahead of its time. It makes you laugh and makes you look at society and yourself. Films that make you do that are the real deal.

What about the shockumentaries, the wave of provocative documentaries about sex, violence, and death that started with the Italian Mondo cane in 1962?

KEREKES: We watched a lot of Mondo films and shockumentaries for our book. Now that the update has been published, I hope never to have to do that again. I have seen enough shockumentaries to last a lifetime. I try to avoid atrocities footage.

One of the better examples from that period was Des morts by the Belgian Thierry Zéno.

Unlike all the others, he was not guilty of exploitation. He made an honest, direct, and confronting film about rituals surrounding death, and it stuck to the facts. It wouldn’t surprise me if Des morts has aged very well.

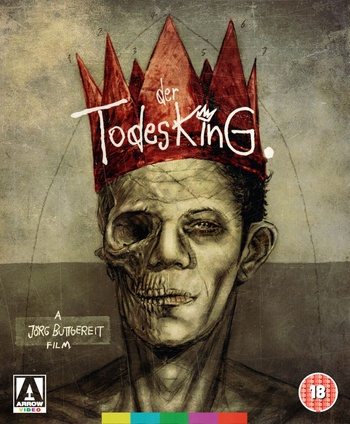

Nekromantik

Offscreen is also paying tribute to Jörg Buttgereit, the innovative German who depicted necrophiles in Nekromantik 1 & 2. You wrote a book about him. Will we ever think of Nekromantik as a classic, the way we now think of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre?

KEREKES: I would hesitate to say yes. Like so many great films and resonating artworks, Nekromantik arrived at exactly the right time and captured the Zeitgeist. Buttgereit didn’t care if the film was banned. He wanted to make the film that he wanted to make and if it was shocking, so be it. That was bold.

What you see is not necessarily what you would expect from Nekromantik, based on the poster with the rotten corpse or the buzz. Jörg Buttgereit made several excellent films. You may not like Der Todesking or Schramm but those are all good films.

Nevertheless, I do not think that Nekromantik will ever become mainstream. For one, it looks too grainy and bad. People can’t see beyond that. If you ask a complete stranger on the street, there will be a good chance that they have at least heard of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. I don’t think that is the case with Nekromantik.

In the early 1980s, the British government thought that it should protect its citizens from films. A censorship body would slice them to pieces or simply ban them. Cannibal Holocaust was one of those “video nasties”. What do you make now of the panic of that period?

KEREKES: Cannibal Holocaust was one of the video nasties that became famous for being banned and immediately attracted a cult following. The minute a government body tries to stop somebody from seeing something the opposite happens: everyone wants to see it.

It was a strange period. We loved those films and didn’t think of ourselves as maniacs. And suddenly films started disappearing because the government panicked. I went to a video rental and all of a sudden, Inferno and Tenebrae, two films by the horror maestro Dario Argento, for whom I had great admiration, had just vanished. It was 1984 and it suddenly seemed as though we were living through Georges Orwell’s 1984. (Laughs) It went further than a prohibition to watch certain films, it was about our civil liberties being confiscated.

Do you know of any similar cases?

KEREKES: It keeps happening all the time. The same things happens or happened with rock music, crime comics, video games… New pop culture emerges, people don’t understand it, fear that their children are in danger, and react very badly. Sometimes it all blows over quickly, but sometimes it doesn’t.

The situation is very different now though because everything is available online. You can find more than you could ever want on Google. The British Board of Film Classification cut a few seconds of blood out of Tenebrae, but today that scene would immediately be circulated online as a meme. Censorship has become pointless and absurd.

MEMENTO MORI: Five Films to die for

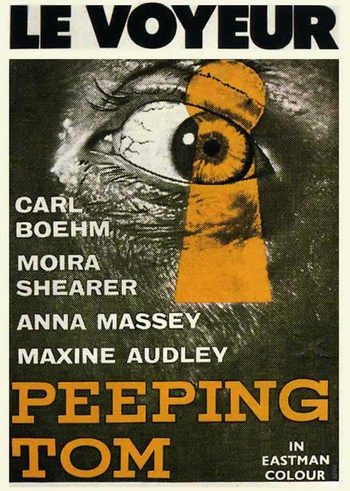

Peeping Tom

1960 produced two masterpieces about psychotic murderers: Psycho by Alfred Hitchcock and Peeping Tom by Michael Powell. But the British press didn’t realize, and they destroyed Powell’s career with their merciless reviews. Martin Scorsese and Roman Polanski, on the other hand, are huge fans of the way in which Powell depicts the story of a murderous photographer who takes snapshots of his victims’ faces at the point of death.

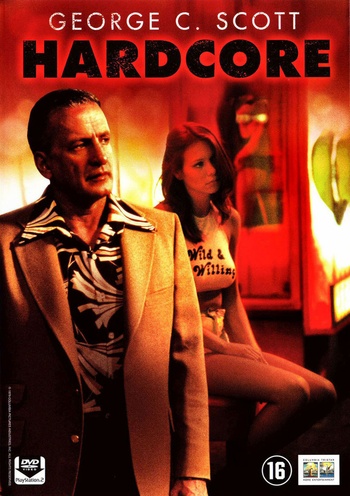

Hardcore

A deeply devout businessman from the Midwest recognizes his daughter, who ran away from a Calvinist youth camp, in a porn film. Disgusted, he ventures into the dark world of the Californian porn industry. But actually, all you need to know is that Hardcore (1979) is a forty-year-old film by Paul Schrader. He wrote the screenplays for Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, but as a director he also occasionally outstripped the mediocrity that he hated so deeply.

Der Todesking

Thanks to Nekromantik 1 & 2, Jörg Buttgereit will forever be remembered as the director who fearlessly but unsensationally spent time exploring the psyche of necrophiles. But the director is deeply knowledgeable about the possibilities of the specific medium of film. Or he explores them experimentally. In the sombre Der Todesking (1990), somebody dies violently on every day of the week. Macabre, but is that wrong?

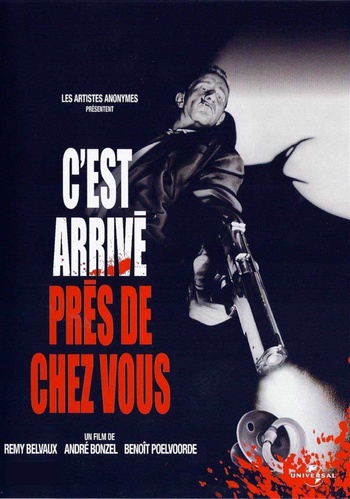

C’est arrivé près de chez vous

A sensation-seeking camera crew follows a self-satisfied serial killer who indulges prodigiously in witticisms, aphorisms, and fragments of verse. The laughter turns to disgust when he rapes a woman while the camera crew film her husband. This 1992 mockumentary by the young filmmakers Rémy Belvaux, André Bonzel, and Benoît Poelvoorde was a sardonic critique of the aberrations of reality TV. Prophetic Belgian cinema.

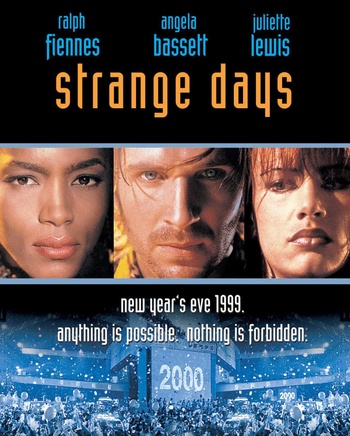

Strange Days

Strange Days (1995) is almost a quarter of a century old but remains one of the best virtual reality thrillers. A sacked former police officer has to run for his life when virtual footage of the police killing a black activist unleashes a revolution. Bigelow got the script of this shocking and jet-black cyberpunk thriller from her then-husband James Cameron. With one incredible scene after the other, the ghastliest depicts the murder and rape of the call girl Iris.

Offscreen Film Festival 13 > 31/3, Various locations

Read more about: Film

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.