In 1971, during a train ride between Congo-Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire, a drummer was so fascinated by the repetitive pattern of the wheels that he later reproduced the rhythm in a studio in Kinshasa. The resulting cavacha became a new current in modern Congolese rumba. A concert in Bozar focuses on the sound of the pioneers.

François 'Franco' Luambo Makiadi, de bandleider van Oké Jazz, later bekend als TPOK Jazz.

Chooka-chooka cavacha: here comes the Congolese rumba

Also read: BelgianArtPrize-winnares Suchan Kinoshita: 'Laat de drang varen om een werk te verklaren'

It is no secret that the Brussels-Congolese guitarist Dizzy Mandjeku played the chorus on Stromae's hit “Papaoutai”. Just focus on that infectious riff, which draws on his decades-long experiences with rumba rhythms. For a long time, Mandjeku toured with Zap Mama, who also are not averse to a bit of Congolese schwung. But Baloji and French-Congolese rappers like Maître Gims and Dadju also found their way into it.

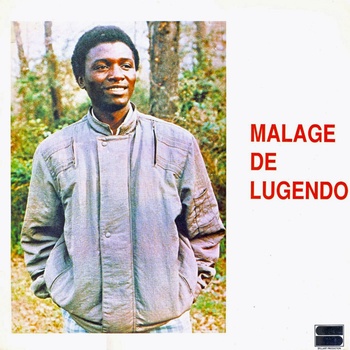

According to Klay Mawungu, these contemporary acts each take the Congolese rumba legacy, which since 14 December 2021 is UNESCO World Heritage, and do their own thing with it. For years, Mawungu has been one of the greatest advocates of modern Congolese rumba in Belgium. He put together the 18-piece orchestra Mythique Rumba Congolaise Internationale (MRCI) soon to play the “Generation Cavacha” concert at Bozar. A few of them are in their thirties, but most have passed the sixty-mark. Like singer and musician Malage de Lugendo, who used to play with Meridjo Belobi (1952-2020), or Meridjo for short, the drummer on the train who developed the typical cavacha sound.

“I grew up with the cavacha style,” says Malage. “As a child in Kinshasa, it was everywhere. Later on, I was in several orchestras and from 1989 to 1995, I was in Zaïko Langa Langa, the band that since 1971 had been developing the cavacha and was led by Jossart Nyoka Longo. Meridjo was still there at that time, and of course he told me about the trip from Brazzaville to Pointe-Noire. It was Zaïko Langa Langa's first trip abroad. He told me that those old types of trains made a lot of noise. (Laughs) So they are nothing like the trains we know here now! The orchestra members, it seems, could not sit still when hearing the rattling, syncopated sound of the driving wheels. Once they arrived back in their rehearsal room in Kinshasa, Meridjo reproduced that rhythm on his drum and the cavacha was born.”

Hip muscles

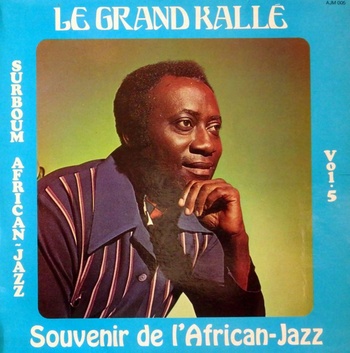

“Since 1953, there have been three major trends in Congolese rumba,” Klay Mawungu briefly outlines his favourite musical style. “That was the year in which singer and bandleader Joseph Kabasele Tshamala, better known as Kallé Jeff (or Le Grand Kallé, ed.), created African Jazz. Many see that orchestra as the first modern Congolese rumba orchestra and the band played for the politicians at the famous Belgo-Congolese Round Table in Brussels.” Their “Independence Cha Cha”, played for the first time on 27 January 1960 at the Plaza Hotel in Brussels, would soon become the ultimate independence song and one of the first Pan-African hits.

“That first movement, in the wake of Kallé Jazz, its guitarist Nico Kasanda and many others is known as 'fiesta',” Mawungu continues his history lesson. “But from 1956, it faced competition from a second movement: odemba. The face of this style was Franco Luambo Makiadi, or Franco for short, with his orchestra Oké Jazz (later TPOK Jazz). If the fiesta style was melodious and more refined in its arrangements, then the more rhythmic odemba looked back at its Congolese roots and made you want to dance.” TPOK Jazz did not stand for Tout Puissant Orchestre Kinois de Jazz for nothing.

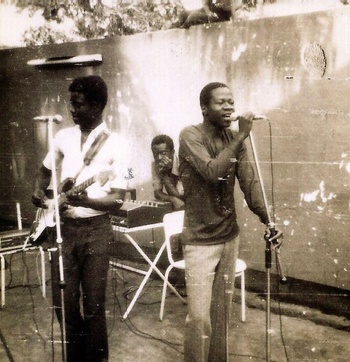

Zaiko Langa Langa.

When I meet my brothers at the café, we still play those songs and cavacha rhythms. I take every opportunity to perform them

The two currents continued to define modern Congolese rumba until the end of the 1960s, when a younger, somewhat more rebellious generation of musicians arrived under the leadership of Zaïko Langa Langa. “They borrowed elements both from the fiesta and from the odemba movement but added that typical fast and swinging rhythm. Earlier orchestras had had drums already, but now they became crucial.” This undeniably had its effect on the hip muscles of young people in the then new state of Zaire.

Diaspora

But it was not only the local discotheques that were enraptured by the hyper-inflammatory mix of rumba and funk. Cavacha was soon making waves in the diaspora. “In the 1980s, the cavacha was an important inspiration for zouk, with Kassav' as its biggest international showcase,” says Malage, who since 1995 has called Brussels home. “More recently, there has been rapper Maître Gims, now Gims, in France,” Mawungu says, before he starts singing the chorus of Gims' hit “Sapés comme jamais”. “Do you hear it? That rhythm, the very base of it, goes back to the rumba, even if he adds other instruments. Everything that wants to be hip today recasts that cavacha style in a contemporary outfit.”

“I admire Stromae and Baloji,” Malage adds. “Instead of just rehashing the genre, they are creative about it, with intelligence and great sophistication.” Meanwhile, the pioneers keep on working. To mark Zaïko Langa Langa's 50th birthday, the orchestra's last configuration was invited to Bozar in February 2020, just before the pandemic struck.

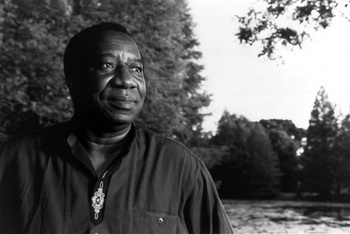

Tabu Ley Rochereau.

World Heritage

MRCI's concert in the same concert temple is in several ways special. It comes two months after UNESCO recognised Congolese rumba as an intangible cultural world heritage. A special moment for many Congolese, because back then this style of music was a way of fighting against colonial rule and Belgian oppression. The MRCI project was launched in the wake of the submission of the UNESCO application by the representatives of the Democratic Republic of Congo (Congo-Kinshasa) and Congo-Brazzaville, the two neighbouring countries directly involved in the creation of the cavacha. The concert also takes place almost 18 months since the death of Meridjo, who died in Liège in August 2020 after a long illness, and fits in perfectly with the Trains & Tracks theme of the current edition of the Europalia cultural festival.

“We bring the original cavacha sound,” concludes Mawungu. “The orchestra includes musicians who were part of Zaïko during different eras and/or later included the rhythm in their own bands and solo careers. There are original composers on stage, like Nyboma or Wuta Mayi, but we also play tracks by the founders of rumba, like Franco or Tabu Ley Rochereau.”

This performance is an another opportunity for Malage to present his culture. “More than that, it is what I love doing the most. When I meet my Congolese brothers at the café, we still play those songs and cavacha rhythms. I take advantage of every opportunity to perform them. The timing may not be ideal with Covid going on and as we cannot play in front of a full house. It will be a bit less grand, but that won't stop us from doing what we do best.”

Read more about: Muziek , Events & Festivals , Bozar , Trains & Tracks , Europalia , Congolese rumba , cavacha , Mythique Rumba Congolaise Internationale