At the heart of a hot Summer of Photography, Bozar is hosting “Resist! The 1960s Protests, Photography and Visual Legacy”, an exhibition devoted to the power of the collective and the apparently unsightly but essential action of a thrown rock and a voice in the street. Curator Christine Eyene is enflaming our minds.

© Bruno Barbey / Magnum Photos

Also read: Josef Koudelka, Invasion Prague 68

Who is Christine Eyene

- Was born in Paris in 1970

- Her youth was marked by encounters with South African artists, who were banned by or fled the Apartheid regime, visiting her house

- She studied the History of Contemporary Art at the Sorbonne

- As a 21-year-old, she learned photography from the South African World Press Photo Award-winner George Hallett

- Since the late 1990s, she has been researching modern and contemporary South African art

- When moving to England in the early 2000s, she became interested in Britain’s Black Art Movement in the 1980s

- As a Research Fellow in Contemporary Art at the University of Central Lancashire, she studies and writes about contemporary African and Diaspora arts, representations of the body and gender in art, and sound art

- In 2010 she embarked on an international career as an independent curator. She was co-curator of Dak’Art 2012 and curator of the African selection of Photoquai 2011

- In 2012 she became part of Making Histories Visible, an interdisciplinary visual arts research project at the University of Central Lancashire, led by Turner Prize-winner Lubaina Himid

- In 2014, she curated “Where We’re At! Other Voices on Gender” during the Summer of Photography at Bozar

- Last year she was appointed curator of the 4th International Biennial of Casablanca, which will take place in the autumn of 2018

“I like to explore different kinds of artistic practices,” Christine Eyene, curator of “Resist! The 1960s Protests, Photography and Visual Legacy”, tells us over the phone from Switzerland, where she is attending the annual contemporary art fair Art Basel, “but activist art will be a recurring element in my work for as long as we have things to struggle against, different kinds of exclusion in society and art.”

Well, the least you can say is that “Resist!”, the focus exhibition that Bozar has planted in the biennial Summer of Photography right in the fiftieth anniversary of May 68, is rooted in fertile ground. The world – both the tangible and the virtual – seems to have been on fire over the past few years, dragging itself repeatedly from deadlock to confrontation. Donald Trump, Brexit, the rise of the far right and xenophobia, and the hostile attitude towards migration were and are met with #MeToo, the Women’s Marches, student protests against gun violence, the Black Lives Matter movement, and so on. These are turbulent times, the powerful often seem to have lost their conscience, and the voices of those who oppose them are growing ever louder and undaunted.

© Heleen Rodiers

| Christine Eyene raises her fist at Bozar

“To me the 1960s correspond to the time when for instance in America, you had the civil rights movement, and in England, Enoch Powell, a Conservative Member of Parliament, gave his ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, a highly inflammatory anti-immigration speech,” Christine Eyene says. “So there is no doubt that there are a lot of parallels between the context of the 1960s and that of today.”

“Then again, speaking from the perspective of a curator with an African background, a lot of the issues that are resurfacing now were already part of my practice. I have been writing and reading and engaging with South African art since the 1990s, and I have personal connections with artists who left during Apartheid and came to live in France in the 1980s. So even though there have been periods in the West where we have felt that everything was okay and that we could look towards other directions than just the socio-political, for me, the unrest within different societies and the political awareness represented in art are issues I have always been sensitive to and aware of.”

Activist art will be a recurring element in my work for as long as we have things to struggle against, different kinds of exclusion in society and art

It is that breadth, both mentally and geographically, that ensures that “Resist!” stretches far beyond the frame of reference of the photogenic protests of May 68, which started as a student movement demanding the democratization and decentralization of the French educational system but soon developed into a general rejection of President Charles de Gaulle’s government, as well as the capitalist order built on consumption, social injustice, and individualism. “The photographs that Gilles Caron and Bruno Barbey took of the May 68 protests are of course iconic,” Christine Eyene says, “but for me it was important to also broaden the scope and show that there were other events than just May 68 in Paris at the end of a decade of social struggle.”

THE NEVER-ENDING STORY

“Resist!” turns our attention to the whole turbulent decade, and thus also focuses, for example, on the marches that Martin Luther King held on Washington and Selma through the visual accounts of Steve Schapiro, the student protests that erupted in Coimbra under Salazar, the Catholic demonstrations in Londonderry, Northern Ireland, or the Vietnam War protests in Japan. And in weaving a thread that stretches up to our day, it even goes much further, with the photos that Gundula Schulze Eldowy took in the 1980s of life on the East side of the Berlin Wall, John Akomfrah’s film Handsworth Songs that focused on the stigmatization of black communities under Margaret Thatcher’s premiership, Oliver Ressler’s three-screen-video Take the Square about the Occupy movements, or the works by Hank Willis Thomas that seem like a prefiguration of the activism of American footballer Colin Kaepernick, who in 2016 protested racial profiling and police brutality towards black people by refusing to stand during the national anthem.

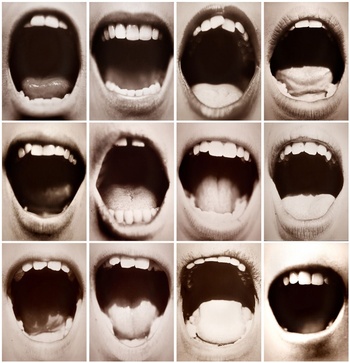

© Graciela Sacco

| Bocanada, 1994 - 2015

Even though there are new media, forms, and themes of protest throughout the decades, one thing that becomes very clear in “Resist!” is that there is no end to the injustice that is at its core. Isn’t that a little bit discouraging?

Christine Eyene: [Laughs] Yes, it can be. I think the overall statement in the exhibition – and that is also why I wanted to open up to the contemporary period – is that we always need to remain aware of what we have and not take things for granted. When you look at the issues with LGBT communities in Europe, technological advance bringing ecological disaster, or the debates in Poland and Ireland about abortion, for instance, you come to realize that the human rights we have in Europe can be reverted. So yes, I think it is endless and timeless. It’s part of our existence, I guess. A never-ending cycle.

But I don’t want visitors to come out of the exhibition feeling depressed. That is why the final section of the exhibition, “Speculating on the Future”, shows contemporary forms of visual activism that are a little bit more “uplifting”, so to speak.

Take the work of Larissa Sansour, a Palestinian artist based in England, who is showing a short video called A Space Exodus, a reference to Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. She approaches the struggle for a Palestinian state from a futuristic perspective. It is a different way of referring to the images that we all know, like what happened when the Trump administration inaugurated the US embassy in Jerusalem and the killings in Gaza. There is also Inverso Mundus by the Russian collective AES+F, which, in an absurd end to the exhibition, creates a sort of inverted, post-protest world, where children are oppressing their elders and the rich have become poor.

The balance between activism and art has always been precarious. How do artists deal with this tension?

Eyene: I see art as a humanistic discipline. Artists are not just artists, they are human beings. They speak from their own experiences and their own concerns. Take Wolfgang Tillmans [a German photographer who won the prestigious Turner Prize in 2000 – KS], who has been looking at subjects that are close to his heart, but not shouting about it. He has been doing work in South Africa in support of the LGBT communities, helping with graphic design and so on, and he did a real campaign for the Remain camp during the Brexit referendum.

The interesting thing is that a lot of the work in the show is not particularly new, but current events somehow find their way into it. Look at how Bruno Serralongue’s work on the Zone à Défendre, the ongoing struggle of farmers and activists against plans to construct an airport in the French municipality of Notre-Dame-des-Landes, became relevant again in April this year when the police raided the place.

Photographers who are going to places to document protest, even though it is not them protesting, are still concerned that these movements have to be documented. People need to know what is happening.

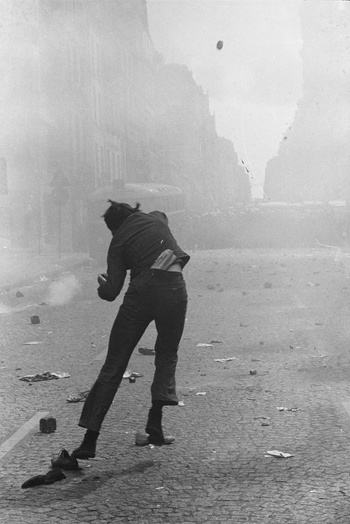

© Fondation Giles Caron

| Gilles Caron's Parisian Cobblestone Thrower (1968)

Is there a direct influence from May 68? Has it proven to be a turning point for the arts?

Eyene: I think it has really influenced contemporary society and continues to do so to this day. And as far as photography is concerned, yes, there is some sort of legacy in terms of photojournalism, but also in the way in which photography is used in other artistic practices. One section of “Resist!” is called “Archival Matter”, where we switch from pure photojournalism to visual arts and lens-based practices where artists also use archives. One of the artists featured is Gavin Jantjes, a South African visual artist who is based between England and Norway. He has been making silkscreens and collages, using photographs from the 1960s by Ernest Cole, to zoom in on the racism he experienced as a “coloured” South African - a racial classification invented by the Apartheid regime.

And the Argentinian human rights activist Marcelo Brodsky is opening the exhibition with his series 1968: The Fire of Ideas, in which he traces archives from 1968 and all the demonstrations and protest movements internationally, showing a broader idea of protest, the truly global character of what May 68 has become the icon of.”

SHAPE YOUR OWN WORLD

That series by Marcelo Brodsky also features two “reactivated” photos that were taken at Bozar during the occupation of its main hall from 28 May until 10 June 1968. The demand for the democratization of education at the ULB resulted in two hectic weeks of artistic protest by, among others, Hugo Claus, Marcel Van Maele, and Marcel Broodthaers, against “the present culture system and its propagation” and censorship. It was an action that walked the blurred line between activism and performance, revolution and orchestration, and links Bozar very concretely to the context in which “Resist!” is now situated. “It sort of brought something else to the project,” says Christine Eyene. “The protest movement is part of Bozar’s story, just like it has been an interest of mine for many years.”

© Larissa Sansour

| a still from Palestinian artist Larissa Sansour's A Space Exodus (2009)

What was it that sparked off that interest?

Eyene: Oh, growing up in Paris as a young black woman. As a twelve-year-old, seeing all of those South African artists passing by our home. People like George Hallett, who won the World Press Photo Award in 1995 for his visual account of Nelson Mandela’s presidential campaign, and Gerard Sekoto, one of the first modernists in South Africa. He started painting in the late 1930s when black people were not even supposed to be artists. In a way, it allowed me to project myself beyond the images that we had and still have of black people and made me understand that you can shape your own world, reclaim the discourse on your own identity, and gear that towards something positive.

For me it was about the art, researching the artists, writing about them. Filling in the gaps I came across as a student at the Sorbonne, the complete absence of monographs on African artists in the libraries. That’s why I felt it was important to write those articles and books myself, do the research, and work on our own discourses. Eventually I went from 2D on paper to 3D within the space as a curator.

Is there one particular work that triggered you?

Eyene: It was really when I came to England, about sixteen years ago, and came across the Black Art Movement of the 1980s, a movement I had never even heard about in Paris, that things developed in a certain direction and I decided to do projects that addressed socio-political issues. Lubaina Himid, the artist who won the Turner Prize in 2017, was one of the artists who was active in the movement. Her work and that of her colleagues opened my eyes to the fact that you can talk about your own experiences in art – in this case young black artists who were students in the Thatcher era – and address difficult issues through art. It became obvious to me that it is really the only way to get to the heart of the matter.

So we’re free to interpret the title “Resist!” as a call to action?

Eyene: I’m hoping that it will, though I don’t want Bozar to become troublemakers. [Laughs] You know, I am personally touched by a lot of things that are happening. As a European citizen living in England, we don’t know what is going to happen with Brexit. I’m also concerned about migration, and I’m always sad and concerned when I see that European countries are increasingly expressing the need to control our borders. My mum is from Cameroon, so even though I was born in France, the generation before me were immigrants, and in a way I’m an immigrant in England as well.

Maybe it’s a bit naïve to think that this exhibition will make people think, but I hope that at least a few of them will. There are still a lot of issues to be addressed, so it is necessary that we don’t get too comfortable in our situation as European citizens.

> Resist! the 1960s protests, photography and visual legacy. 27/6 > 26/8, Bozar, www.bozar.be

> Summer of photography. > 14/10, various locations, www.bozar.be

Read more about: Expo , summer of photography

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.