Graffiti artist, performer, sketch artist, sculptor... Vincent Glowinski, the artist who surfaced in 2010 when he was forced to cast off the skin of “urban legend” Bonom, is many things rolled into one. The exhibition “Sketches” ties this impressive tangle of manifestations together with great intimacy.

Vincent Glowinski and his elusive selves: "I am many different things at once."

Being an image and staying an image is foolish.” Vincent Glowinski utters these words more than once during our encounter at Mathilde Hatzenberger Gallery. It is a way of rebutting the bartering over his identity, patterns of expectations, and attempts at recovery. “During the exhibition at the Botanique, somebody wrote, very bluntly, in the guestbook: ‘Go back to the streets.’ It attests to a kind of imagined purity that in no way represents humans in all their complexity. I am not the pure idea that some people have of me. Life is to be found precisely in the continuous transition from one thing to another. I am many different things at once.”

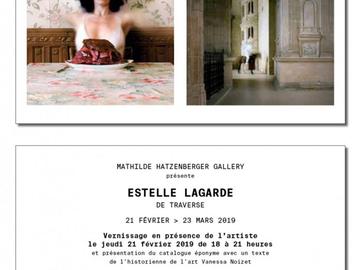

This dynamism, and this elusiveness, is at the very core of Vincent Glowinski and his artistic practice, which ranges from drawings and sculptures to dance productions (under the wings of Wim Vandekeybus’s Ultima Vez) and performances (including with jazz drummer Teun Verbruggen in Duo à l’encre). It also extends to graffiti – the discipline he practiced under the moniker Bonom until 2010, declaring the public space of Paris (where he was born) and Brussels (where he moved to study at La Cambre when he was 19) to be his canvas, and conjuring immense portraits of animals and skeletons in breath-taking locations. This dynamic practice is also clearly in evidence at Mathilde Hatzenberger Gallery. In this intimate setting, he is taking his first steps in the Brussels gallery scene, after institutional exhibitions at L’iselp in 2014 (“Bonom, le singe boiteux”, with his partner in crime, photographer Ian Dykmans) and the Botanique in 2016 (“Mater Museum”, with his mother, Agnès Debizet).

The more my trajectory develops in Brussels, the more paradoxical my position becomes. And the more interesting, I think.

However small the exhibition “Sketches” may appear initially, it has a huge impact. Because what you see is not all that you see. Because the drawings, collages, and sculptures reach out beyond this space. Because they contain a vitality and an inspiration that squirm, claw, or reluctantly find their way to your heart. Take the train track in the window, on which little blocks serve as carriages, piled up carved wooden dolls take your breath away as burial mounds, and the wolf marionette, also made from gathered wood, serves as the locomotive. Or take the painting that alludes to the falling fox of the Cité Administrative, the leather skin on which a naked woman strokes herself, or the sketches that make the soul-stirring graffiti of the emaciated, naked man at the Hallepoort/porte de Hal loom large. It is in this cluster of interrelated forms that “Sketches” reaches straight for the core: drawing. “That is where it all starts,” Vincent Glowinski says, “whether the work then evolves into sculpture, graffiti, stories, or performances. Drawing is what brings about the movement and narration.”

Did you actually start out in drawing or graffiti?

Vincent Glowinski: I started doing graffiti, letters, when I was at school, not doing anything of any great interest at all. It was a kind of game, a way of self-discovery. I stopped after two years. The letters were not enough. At the time I was taking drawing classes, as a preparation for arts school, and I took those drawings back to the streets, combining the two elements. Graffiti was a way to explore the city, to climb, to break into abandoned areas and buildings. It redraws the city, changes its face. When you spend all your time balancing on gutters, you start living completely differently. I integrated all this movement and scale into my drawings, as the mark of my journeys.

© Ivan Put

| Vincent Glowinski

That sounds like it is still a necessity.

Glowinski: Well, graffiti is the most complete activity for me. Artistically, socially… Graffiti is the answer to everything. But it is also very difficult because there are so many boundaries and so many transgressions. It doesn’t stop at the wall, reaching and painting the place itself, but you also have to authorize yourself to do it and to paint precisely that subject. So it is more difficult, but also the most right. The price you pay for all this is fear. I am not always ready. It requires somewhat violent emotions. Gentle thoughts aren’t enough to make me do it. [Laughs] That is precisely why it comes in waves, shocks, and intense moments. It is the response to a profound feeling of dominance, in the city and in life; uncompromising, autonomous. That is artistic freedom…or rather liberation. When it works, I feel a profound sense of relief and I am at peace with the world.

THE APE

2010 saw the end of Bonom, the near-mythical pseudonym under which Vincent Glowinski painted enormous tableaux on Brussels’s façades. Murals that looked like they came straight from a book of fables or myths and were bursting with playfulness, profundity, poignancy, and soul. “The last painting I did was deeply symbolic: the quartered gorilla opposite the KVS. Because once I was unmasked, I had already been assimilated and recuperated as an image, politically. I felt as though I was no longer my own. That ape had no volume, it was two-dimensional, strung up, like Bonom’s skin. A skin that I myself had shed. I was elsewhere, and Bonom was dead.” A period followed in which Vincent Glowinski left the streets, but he later returned, dressed in black, to paint black paintings. “It was very rough, just paint on a wall. Like phantoms, as though the subjects had no bodies. Imagination was gone and it had been replaced with a violent confrontation with the city. A bad accident brought some calm. I ended up in more institutional projects and started making productions. People constantly addressed me as Bonom, but I no longer recognized the name. I was no longer that character; I no longer wore a mask.”

Is the moment when you started drawing people linked to the removal of that mask and the fact that you became more intimate?

Glowinski: It was always intimate, but I did start accepting that more. People are much harder to draw. You can mess up an animal, but not a person. The reactions to people are also very different, everything becomes much more serious. But for me they are the same subjects and the same emotions. The animals were always metaphors, like the fables of La Fontaine. But with animals there is always a kind of detachment. A bloodied animal is acceptable, a bloodied person is a terror.

The first person I painted was the masturbating woman on Louizalaan/avenue Louise. It was very intimate and very symbolic. Graffiti has always been an intimate act. But people quickly get used to a big whale on the sheeting of a scaffold, it gets assimilated. That is unbearable to me. Because the act is still a transgression. I overstep my boundaries to do this. Graffiti and street art have changed so much, just like the public’s appreciation, while I remain a wounded individual in society. It drives me crazy when people say: “Oh, that’s beautiful, keep up the good work.” That is unacceptable. [Laughs] Then you take it up a notch.

Graffiti and street art have changed so much, just like the public’s appreciation, while I remain a wounded individual in society.

You are looking for a reaction?

Glowinski: If I start painting, it is my reaction.

But there is also a reaction from the audience.

Glowinski: There has to be some kind of reciprocity, yes. The action that I do has to be palpable. If I cut my arm off because I feel pain and people react: “Great, keep up the good work,” there is a problem. The other person is supposed to feel that pain with you. When I cut myself in the stomach, the other has at least to feel some stomach cramp. I can’t be the only one suffering.

THE PHANTOM

That pain is palpable. So is the euphoria. As are the fear, the passion, the rage, and the sadness. At Mathilde Hatzenberger, there are six sketches that refer to one of the most penetrating works that Vincent Glowinski gave the city. “Three years before I made that graffiti, I had made a similar sketch of my father, naked, with his hands covering his genitals. But I didn’t dare to make it into a painting. He had just died, and it was too intense, also for my family. I could not appropriate it to that extent. But when I found the sketch again later, I still felt that same emotion. The painting at the Hallepoort/porte de Hal is the result of the idea to stop painting. One last symbolic work. I redrew the head so that it no longer looked like him, but became more of an idea – my father from certain perspectives: the Shoah, nudity, humiliation, death. You see somebody floating, as though they are rising up out of a crematorium chimney. It is completely different to the woman on Louizalaan/avenue Louise, who is very dominant. This is a subject that is floating, he is dead, a phantom.”

That same image was also exhibited in marionette form at the “Yo!” exhibition at Bozar.

Glowinski: That was actually its original form. When my father died, I sculpted his portrait, like a little reincarnation of him. The work at the Hallepoort/porte de Hal is the representation of that marionette. The same subject can take on different forms and a different life. Sometimes I have a greater need to have a small marionette that fits in my hand, sometimes the work has to spit the world right in the face. These are all feelings, intuitions. But the same subjects recur. It is as though the subject is in the air and can adopt different forms as it floats about. To me all of those forms are the same thing. The soul is the core. That little soul of the Jewish father who floats in the air may incarnate in various ways.

There are many references to the Shoah in your work.

Glowinski: My work has multiple subjects, and that is one of them. I have a mixed background, Jewish and Catholic, and it is expressed in my visual language, which combines the Gospel and Greek mythology with the Jewish eradication of all imagery. Thanks to those mixed roots, I can access the world of the image beyond that enormous prohibition, that huge grey monochrome. That visual language, or its absence, is there all the time.

And it belongs to you and yet…

Glowinski: It doesn’t, precisely. It prohibits and authorizes.

THE COURT JESTER

That is the knot in Vincent Glowinski’s artistic existence. The constant movement between prohibition and authorization, between acceptance and censure, between embrace and the urge for independence. A free spirit with an overwhelming artistic vision and the visual language to express it with both integrity and impact, but also – very simply – a person who is part of society and searches for ever-changing ways to survive in it.

© Ivan Put

| Vincent Glowinski

At the end of the spring, that paradox will result in a commission from the City of Brussels. “It is a commission for the public space and that changes everything. In the public space, I don’t feel inclined to adapt myself. It has to come completely from me. Because these are my most intimate feelings. But intimacy is unacceptable in public space, so it will be difficult. I still have to make the work, and perhaps I am talking about it prematurely, but at the moment I am thinking about a work packed with symbols, hidden messages, and multiple interpretations that brings the position of the artist to the fore. Like the ape, the subject that escapes, and the image, the skin that remains as an envelope and surface. I feel as though my position – prohibited but recognized – is like that of the court jester, the ape on duty but also a figure who is in a unique position as the only person who is allowed to criticize the king. My work becomes a critique, accepted but ultimately not really acceptable. The more my trajectory develops in Brussels, the more paradoxical my position becomes. And the more interesting, I think.”

There has to be some kind of reciprocity. If I cut my arm off because I feel pain and people react: “Great, keep up the good work,” there is a problem. The other person is supposed to feel that pain with you.

Is that position tenable? Quite a few graffiti paintings have been popping up in the city recently, and often they are linked to you. Do you recognize authorship of it?

Glowinski: Mais non, of course not. I think this author is anonymous. And it is important that he stays anonymous. But I can talk about it. [Laughs]

Alright, what did you think about the penis in Sint-Gillis/Saint-Gilles?

Glowinski: Touche pas à mon zizi! Clever, wasn’t it? I was very impressed by that graffiti and the space it occupied. A lot of people called it a penis at rest. That was not my first thought when I saw it, for the first time. [Smiles] In my eyes it was the image that a child has of his father’s penis – something very natural and sometimes even funny. But all anybody could talk about was that it was flaccid. That tells you a lot because it means that people imagined it erect. And then there was the fact that it was located opposite a Catholic school, that was really something. What does that penis really tell us? Nothing. It is merely shown and allowed to exist. Whatever it says is imposed from the outside.

A lot of those recent works are very intimate, like the naked woman on the Varkensmarkt/rue du Marché aux Porcs. You were just talking about the impossibility of intimacy in the city.

Glowinski: Intimacy in the public space is a revolutionary act. It is to import the individual into the collective, and that is a paradox. I see the violence that everyone experiences as an individual in society. While making graffiti, I have a profound wound, a frustration that gives the impression of gaining the upper hand, but actually restores balance. Not through compromise, but through a shock. To me, compromise is not a livable solution.

Vincent Glowinski: Sketches > 28/4, Mathilde Hatzenberger Gallery

Read more about: Expo , Vincent Glowinski , Mathilde Hatzenberger Gallery

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.