In July 2018, BRUZZ was in Yerevan, in the middle of the jubilation that followed the peaceful Armenian revolution. This report features two young film-makers whose respective short films, which can currently be seen at the Bridges festival at Bozar, convey an insatiable thirst for freedom and change.

"It is very interesting to be here at this time, I think. Of course, two months ago you would have really felt the spirit of the uprising in the streets. But now people are different, they smile so much,” says Seda Grigoryan, who is 28 years old, with a slender build and a determined, confident air. It is mid-July 2018. At the end of April, the young film-maker immersed herself, camera in hand, in the euphoria of the large-scale peaceful demonstrations in the centre of Yerevan which would force the then prime minister, Serzh Sargsyan, to cede his position to the young and charismatic leader of the opposition, Nikol Pashinyan, the standard-bearer for the Velvet Revolution. “The day the prime minister resigned, there were no more ‘hellos’ in the streets, it was ‘congratulations’!” says Seda Grigoryan, who is still amazed today by the speed with which the former corrupt government was brought to a halt. “What we see happening every day since the revolution is like a scene from a film, it’s unbelievable.”

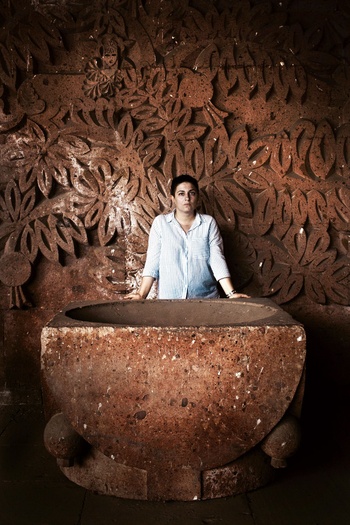

© Sophie Soukias

Having fleetingly crossed paths in the premises of the professional part of the Golden Apricot International Film Festival, we find the young woman once again at 7 pm at Charles Aznavour Square in front of the Moscow Cinema, the epicentre of the festival, which is in full swing in the capital. This year, star film-makers Asghar Farhadi and Larry Clark are among the members of the jury. Way Back Home, Grigoryan’s documentary short, is featured in the Armenian panorama, a separate section from the competition. The streets, which are deserted during the day because of the sweltering sun, are now packed. At night in Yerevan, under the fairy lights, a warm, family atmosphere reigns. Seda Grigoryan has removed her black suit jacket to reveal a festive flowery dress. Her long, brown, wavy hair is freed from its elastic band, suggesting that this is an evening for relaxation. No small talk tonight, the young woman takes us away from the glitz of the festival to a place that she loves.

On the way, mysterious polyphonic singing seems to emanate from the walls of the wide Soviet-style streets. The voices become louder and louder until the source is revealed to us, as we emerge from an underground passage. On a concrete stage, a trio of young girls sing in chorus before an audience that is seated comfortably on steps. “Moscow Cinema’s Open-Air Hall was to be taken down in 2010, but a public campaign initiated by art students, architects, and other lovers of culture stopped the process,” explains Grigoryan, taking a seat. This summer, the place is staging a number of artistic and musical shows. In the performance by MIHR Theatre and the Tiezerk Band, participants scattered throughout the audience take it in turns to read an extract from Unreal Stories from My City, in which the director of the company shares his impressions of Yerevan. Suddenly, the microphone falls into Grigoryan’s hands: “And what do you think in such moments? That I’m definitely gonna die now.”

The day the prime minister resigned, there were no more ‘hellos’ in the streets, it was ‘congratulations’!

It has started

An activist since the age of sixteen, the young woman has, for a long time, directed videos and written for CivilNet (an independent online newspaper that played a crucial role in the various Armenian uprisings). She has made a habit of entering the fray to demand more democracy in a post-Soviet society that is infected by corruption and embroiled in skirmishes with Azerbaijan (a conflict dating back to the devastating Nagorno-Karabakh War between 1988 and 1994). “In 2006, I was covering a civil society campaign as a media intern and I had never heard of such a thing. The group of activists wanted to wake society up, restart the brains of the people after hard times when there was no space for human rights, but only for bread-and-butter issues. Sksela, which means ‘it has started’, was one of the first civil-society movements. I fell in love with them and the next time, I came as a member!”

Doing a master’s in London in 2017 gave Seda Grigoryan the opportunity to make a fourth short film. The documentary Way Back Home follows the Canadian actor Arsinée Khanjian in her campaign for democratic transition in Armenia alongside other celebrities of the Armenian diaspora, such as her husband, the film-maker Atom Egoyan, and Serj Tankian of the hard rock band System of a Down. Together, they travelled around Armenia to observe the 2017 parliamentary elections. “I personally voted for Nikol Pashinyan’s party,” says Grigoryan. “Because they were the only fresh entity among the candidates. A lot of them are friends of mine. They are young, very passionate, honest, and dedicated people.”

On 9 December 2018, the bloc led by Pashinyan won the early legislative elections by a landslide, removing the former president Sargsyan’s party from parliament. “Now the old ruling power is gone, we are entering a phase of healthy political discourse, in which we will openly criticise Pashinyan’s team while still celebrating all the achievements of their party,” Grigoryan writes on Facebook-Messenger. “I hope we can keep the spirit up and not let doubt take over.”

A fish in an aquarium

Diana Kardumyan, aged 36, with kind eyes, a smiling face, and short-cropped hair, is just as excited as Grigoryan is about this historic turning point, which is personified by Pashinyan. She likes to use the French version of his first name. “Nicolas is our cool hero,” she exclaims when the name of the leader of the revolution comes up in an animated conversation between two young people who have just fallen into step behind us.

Kardumyan is keen to take us to see a remnant of Soviet/Armenian architecture that she is fond of. “I wanted to show that Armenia is not only newly built apartments and ugly buildings. There used to be taste.” At street-level at the Republic metro station, the ground opens up into an immense pit that contains a fountain in the form of scallops, harmoniously layered over each other like so many petals of a flower. The masterful work, completed in 1981, was created by the architects Jim Torosyan and Mkrtich Minasyan.

© Sophie Soukias

The history-of-art lesson continues in the Mirzoyan Library, a splendid Armenian pre-Soviet dwelling that has been converted into a trendy café, art gallery and photobook library. “This is a very unique place. I come here with my friends from time to time to feel the atmosphere.” The house extends over several floors with pretty wooden terraces overlooking a bucolic backcourt. Kitsch and retro objects scattered throughout the different spaces add to the timelessness of the place.

In an hour, Kardumyan has a meeting in another city-centre bar with a producer who has noticed her new short film. In the highly stylised Tombé, also included in the Armenian panorama section of the Golden Apricot Festival, the nightmarish experiences of an employee in a restaurant one night serve as a metaphor for the fate of Armenia as a whole. “The protagonist is like a fish in an aquarium. Like her, we, the Armenians, haven’t been complaining for years.”

Born in Nagorno-Karabakh, Diana Kardumyan moved with her family, in 1992, to a small town not far from Yerevan to escape the war raging in the self-proclaimed republic following the breakup of the USSR. With the support of her parents, a driver and a housewife, she enrolled in the brand-new cinema department of the Yerevan State Institute of Theatre and Cinematography in 1999. “The conditions were awful because we didn’t have any equipment,” Kardumyan recalls. “Our teachers would describe to us the films that we should have seen. Can you imagine our hopelessness? They would tell us about Orson Welles, Eisenstein, etc. When I finally saw their films, I thought the descriptions were better because our hopes were so high.” (Laughs)

One thing is clear: the euphoria is gone and now it’s time to act.

Patience

Though cinema in Armenia has had time to develop over twenty years, the sector still faces major challenges. “The people who get money are the ones who have already made ten feature films, often bad quality ones, whereas the ones who really need support don’t get anything,” says Kardumyan. “As an independent film-maker, I made my short films with the support of my parents and friends, and a small amount of funding from our cinema centre. Short films are great because they allow you to be creative, but there’s this feature film I would really like to make, and I would need serious funding.”

The Velvet Revolution, with its cultural and intellectual base, has raised hopes of a new era for independent film-makers, with whom Nikol Pashinyan has offered to work hand in hand. “Following an open letter that we wrote, we started to work on a cinema law with members of the new government,” says Kardumyan. “They are very young but highly motivated, so we should just let them work.”

Five months after we met amid festivities in the Armenian capital, in the days following the Pashinyan team’s parliamentary victory in December 2018, the film-maker is still advising patience. “These are only their first steps. One thing is clear: the euphoria is gone and now it’s time to act.”

BRIDGES. EAST OF WEST FILM DAYS 16 > 20/1, Bozar, www.bozar.be

Way Back Home & Tombé: 19/1, 15.00

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.