Keith Haring died in 1990 at the age of 31, but in his short life he left an indelible mark on art history. His iconic images are the subject of an exhibition that is coming to Bozar from Tate Liverpool. We spoke with curator Darren Pih and a number of Keith Haring's friends from the vibrant New York art scene.

© Keith Haring Foundation / Collection Noirmontartproduction, Paris

About Keith Haring

- Born in 1958 in Pennsylvania. Develops a passion for drawing as a child

- Attends the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh

- Goes to New York in 1978 to attend the School of Visual Arts

- Experiments with chalk drawings in the subways and with videos, collages and performances in nightclubs

- Develops a unique visual universe with bold lines and vibrant colours

- Is featured at Documenta and the São Paulo Biennial in 1982

- Gradually takes an activist stance in his work, fighting racism, homophobia, and child poverty

- Has his first solo museum exhibition in 1986 at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam

- Opens his Pop Shop, where kids can buy his work cheaply

- Becomes very ill in 1988, and dies in 1990, at the age of thirty one, from HIV-related complications

“In this age of division, Trump, and building walls between people, you need unifying figures like Keith Haring who sort of poke through hatred,” says Darren Pih, curator at Tate Liverpool, when we speak to him about the Keith Haring exhibition that is currently being moved from Merseyside to Brussels. “You can see that that's why Keith Haring still has an effect in 2019. There is a sense that he somehow still communicates this ideal – the way that he was an openly gay man who was very confident, very optimistic, and who celebrated sexuality. That still seems to communicate in a very clear way in 2019. Because we still have homophobia and HIV stigma, there's still racism, there's still all these issues that Keith Haring was responding to in the 1980s.”

A KIND VANDAL

The first traces that Keith Haring made on earth before he became the icon that he is now, are to be found in Kutztown, a small, overwhelmingly white town in Pennsylvania. From his earliest years, he exhibited an intense hunger to draw, nourished by his father and by his obsession with Walt Disney and the books of Dr. Seuss, as well as by the comics that he would find in the Sunday newspapers that he delivered daily as a paperboy between the ages of 12 and 16. He and his childhood friend Kermit Oswald would kindly vandalize the neighbourhood before they both enrolled at the Ivy School of Professional Art in Pittsburgh, where Keith Haring very quickly dropped out. Real art and desire beckoned him to New York, where he went to study at the School of Visual Arts.

“When he first landed in New York City in 1978,” Darren Pih says, “there would have been relatively few opportunities to present work in conventional art spaces. The city was bankrupt, and that created a very vibrant, living culture downtown, up in the East Village. You had cheap rents and empty store fronts and warehouse spaces that became sort of a magnet. So you had this inward migration of like-minded artists, musicians, filmmakers, and poets, who created their own living culture. In the subways, on the streets, and in nightclubs such as the Mudd Club and Club 57.”

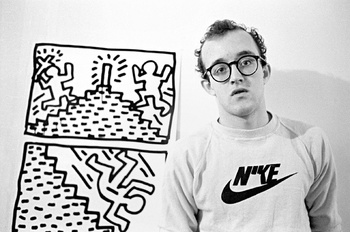

Keith Haring in 1982. The nerdy-looking kid from Kutztown, Pennsylvania, on his way to become an icon

At Club 57, located at 57 Saint Marks Place – and currently an Institute for Mental Health – Dany Johnson worked the turntables as the resident DJ. “Club 57 was based in the basement of a Polish Church,” she says laughing. “It was set up like a rec room. You would walk in the door, you went down a few steps, and in the door there was a little area that was fenced off from the rest. You would go inside after paying your one dollar or three dollars at the door, and at the left there were a bar and a DJ booth, while to the right there was a jukebox and a couple of couches, and to the end there was a little platform for a stage.”

It became the setting for wild parties and artistic experiments. A space where a Monster Movie Club gathered, where the students of the School of Visual Arts experimented, where visual artist Kenny Scharf, manager Ann Magnuson, photographer Tseng Kwong Chi, performance artist John Sex, countertenor Klaus Nomi, and Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat – among many others – did what they wanted to do and were who they wanted to be in absolute freedom. “Totally!” says Dany Johnson. “Because we were protected by the Church. The owner's mother had helped by offering donations to found the church and because of that they gave him control of the basement. At first I think he did some Polish-style stuff like polka bands, and after that he let postpunk bands come in. We never got in trouble, we got away with everything. The owner once said that the punks were better-behaved than the Polish people. Whenever anybody complained about our club he used to say: 'Evil people belong in a church.' (Laughs) It was a membership club, so anybody who was a member could propose something and do it. Keith started organizing shows and performances, he was game for anything.”

Keith was open to all influences, from graffiti to pop art, and from Walt Disney to hieroglyphs, ancient art, and calligraphy

“The first impression that you would have of him was that he was shy, but that went away pretty quickly. (Laughs) He had a great sense of humour and a great sense of fun. He loved music, he loved to dance, and he was really knowledgeable about all different art movements, about poetry, he was interested in spoken word and video. He once put together a Xerox art show, with collage-type stuff you would paste together and take to the copy shop. His stuff was great, he used to paste them around East Village. He also once did this really funny video, Tribute to Gloria Vanderbilt, where he put on lipstick and in front of this fisheye lens he started dancing around to 'Money' by the Flying Lizards. I loved that stuff.”

Due to the unconventional place that Club 57 inhabited during its fifteen-year existence, from 1978 until 1983, the New York Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) decided to devote a retrospective to it in 2017. “It's so funny,” Dany Johnson tells us, “at the time people thought that we were just silly and not to be taken seriously. Probably people from Danceteria or the Mudd Club thought that we were a joke, but hey, look at the MoMA. And it's true, if , if you think about it afterwards, all the really talented people who came out of there who went on to do other stuff, it is pretty amazing. I would not have thought that possible at the time. I mean, Club 57 started as a film series, with a Monster Movie Club, and people showing anime, animation from the 1930s, Kenneth Anger films…underground stuff you could only see if you projected it.”

Even cult director John Waters showed his gratitude for those five years of experimentation. “He said the show at the MoMA was like a highschool reunion from hell, yeah, I heard. But just this one thing about John Waters… We worshipped him, and if he had come to Club 57, it would have been the news of the year. It would have been a sensation and we would have gone completely nuts. As far as I know, he never set foot in our club once. But hey, we were very glad he came to the party. Too bad a lot of our members weren’t there to see it.”

WILD STYLE

““At Club 57, a lot of the members were people who came from somewhere else, some suburb, and got there and just felt the relief of: ‘I can be whatever I want to be now’,” Dany Johnson continues. “Keith just fell in love with the energy here. And I think it's very much because of New York that he made what he made. Because of the fact that there wasn't so much need to have money at the time, you could really do stuff. You had the spaces and places to do so. You had things like the 'Times Square Show' in 1980 (featuring work by Nan Goldin, Kiki Smith, Kenny Scharf, Basquiat, and so on, ks) when Times Square was kind of run down. And people took this space and they did a fabulous art show in it.”

It was at that “Times Square Show” that Keith Haring met the graffiti artist, filmmaker, and hip-hop pioneer Fred Brathwaite aka Fab 5 Freddy, famous for bridging the distance between the street and the gallery. “The 'Times Square Show' was a very famous exhibit in what was referred to as a massage parlour that used to be in Times Square,” Fab 5 Freddy recalls. “But they actually used to be whorehouses. The building was available, empty, and a group called Colab (Collaborative Projects, Inc., an avant-garde artist collective operating since 1977, ks) came together and put on this massive art show there which was open to all kinds of downtown interesting artists at the time. I came and installed two paintings in the show, and Lee Quiñones (fellow graffiti artist, ks) was with me, when Keith walked into the room. He turned to us and said: 'You guys need to know about the guy that did this, Fred, he's a part of the Fabulous 5 (a Brooklyn-based graffiti group, ks), he's friends with Lee, and these guys are incredible artists!' And Lee and I were standing there looking at each other like 'What's going on? Is this some kind of a joke?' And then John Ahearn (the twin brother of Charlie Ahearn, director of Wild Style(1982), the first hip-hop motion picture that featured Fab 5 Freddy, ks) walked into the room. He was one of the organizers of the show and he turned to me and said: 'Well Fred, are you happy with the installation?' And at that point Keith turned and looked, and he flushed bright red, because he was so embarassed. It was a huge laugh, a very funny moment, and we became very good friends at that point. We started to hang out together and talk about graffiti and all the stuff he was to become famous for.”

“Keith Haring admired those graffiti artists,” Darren Pih adds. “He liked the hyper-stylized graphics on trains and on the walls. In the journals, he writes about this idea of the spraypaint flow. But he associates that confident, immediate, unhesitant line, which is a part of that wild style graffiti that he saw in New York City with abstract painting, with Jean Dubuffet and Jackson Pollock. He was open to all influences, from Pierre Alechinsky to pop art and Roy Lichtenstein, and from Walt Disney to hieroglyphs, ancient art, and calligraphy. It's that fundamental openness that makes him absorb the energy of his time. So he admired graffiti and he respected it, but he was not a graffiti artist. He wasn't clandestine, he wasn’t breaking into train yards and spraying graffiti in that manner. He was very public about it, doing it at rush hour, in the subway, and being arrested. It was chalk drawings on advertising panels that were like black canvasses, which he used to express an idea in the moment, to be seen in the moment. So I think it's more a regeneration of pop art or a form of pop performance art on the streets. But the proximity to the graffiti art scene, gave his work this edge.”

According to Fab 5 Freddy, that was also a form of respect. “When he came up with the idea of The Radiant Baby, that he would put on a corner or on a sign, that was a breakthrough for him. He wanted to have his own mark, his own tag, he didn't want to do the things that were typical at the time – your name and how you wrote your name etc. – because he didn't want to be 'this white guy'. He was very sensitive to the complexities of white privilege if you will, a very common thought and discussion now. Keith inherently understood the complexities of race, so he didn’t want to come in and just write his tag. He wanted to make a unique contribution.”

AN ACT OF LOVE

“Then he also began to make these little buttons, of which he would keep hundreds with him, pockets full, and he would give them out to anybody he met. As if it was a presidential campaign,” Fab 5 Freddy continues. “They were a gift, an act of love, and something he would continually do, always wanting to make things affordable and accessible.” Like the Pop Shop he opened at 292 Lafayette Street in 1986. “That was when Haring was already really known,” says Darren Pih. “He was being collected, he exhibited internationally, and he was seen in the company of Madonna, Andy Warhol, Grace Jones, and so on. He could see his work was becoming less accessible, more exclusive, and less affordable. His work was becoming less connected to ordinary people. By that time, he had also stopped making his chalk subway drawings because they were being stolen. I think he got this idea from Andy Warhol, that his images, this whole visual universe he created could be replicated into pin badges and T-shirts and merchandise, and it could be made affordable. As a way of retaining a connection to ordinary people on the street.”

After all the partying had died down and many people were getting ill, he stayed a loyal and generous friend

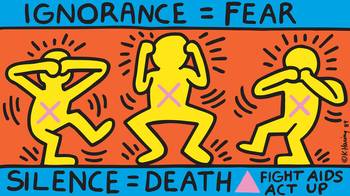

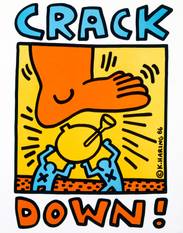

And that opened the door to the evolution of his images to icons. “From early on, Keith Haring saw how he could use his images as a platform for protest, to trigger a reaction,” Darren Pih explains. And to build bridges. “So he lent his voice to the gay community, affected by the AIDS epidemic, to children living in poverty, to the global anti-Apartheid movement in the 1980s by using images which communicate as powerfully as paintings but they're also scalable, they can be cloned and replicated and scaled down and turned into pin badges or T-shirts or posters, and distributed at protest rallies. I think he really did quite quickly understand that he could use his platform to communicate about issues that were important for his generation. Keith Haring understood the power of images in society, the way in which global protest movements in the 1960s could be mobilised behind simple images and slogans like ‘Ban the Bomb’, that would have this politically viral effect. In a way his work is a kind of visual activism. He understood that you don’t have to be in the presence of a work of art to understand the message and that you need all platforms of communication to be activated to get your message through. I think it makes his work interesting, but at the time it also affected his reputation.”

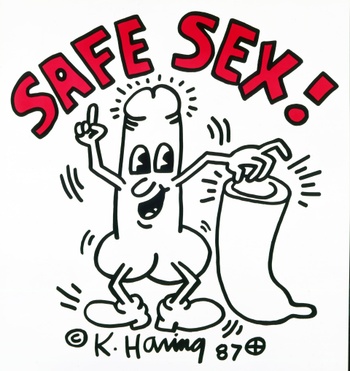

© Collection Emmanuelle and Jérôme de Noirmont, Paris

| Safe Sex! 1987

This did not escape the notice of Bill T. Jones, the world-renowned American choreographer, dancer, writer, and artistic director of New York Live Arts. “For a while he was treated almost like an embarrassment,” he says, “something that had happened, a slippage of taste or awareness. They would say: 'He was a really good social presence, but he wasn't a great artist.' In other words: he was there with those brown- and black-skinned people and he was fighting racism and fighting homophobia, but it wasn't about the art really, it was about something else. That is the biggest put-down, when you are trying to change the paradigm in the art world. Like with graffiti, which was an expression of the underclasses, the undereducated, the 'great unwashed'. There was a risk in considering it art. That's what the art world is like. I think he was a very sincere dude. He was naïve like many of us. He didn't understand in some ways what he was actually doing. You don't cross racial lines as easily in this country.”

THE SOUND OF A BRUSH

Bill T. Jones first met Keith Haring when creating the choreography for a piece called Social Intercourse (1982), for which he was to make the posters. “There were people telling me that the choreography reminded them of the drawings of this young guy, called Keith Haring. And it just happened to be at the time when Arnie Zane, my companion and collaborator, and I were heading up to Kutztown University, where we met a very adventurous man in the art department. He was programming a lot of performance artists to come to this small school to do workshops. He mentioned a brilliant former student who was making great waves drawing on walls in New York City. And it was actually through Kermit Oswald, his childhood friend and partner in crime, that I first saw Keith’s works on paper. He told me they were sort of partners in crime, these young, bright people in the art department who did these things which verged on vandalism, like creating these ephemeral messages by burning salt into grass. I think that his mark making must have originated there with Kermit. He gave me Keith’s address, and within a week or two after visiting him, Keith gave me three beautiful drawings that became the posters for Social Intercourse. That's how I first met him. And we would hang out at Keith’s apartment, where he was surrounded by young people, often Puerto Rican boys, and they were much involved in the night scene. He was very much appreciative of black and Spanish culture, and we were both gay, which gave us other areas of contact.”

© Tseng Kwong Chi

| Keith Haring in a subway car in New York, circa 1983

A performance piece, called Long Distance (1982), presented at The Kitchen (the influential art and performance space in New York, ks), saw Bill T. Jones dance to the sound of a brush on “huge pieces of what we called butcher paper. Those were pieces of probably eight feet tall and twenty feet long, that Keith would roll out. As I was dancing, he was making his hieroglyphics on the back wall, the only sound being him dripping the brush and touching the surface of the paper. And then, at some point he told me he was going to have a major show in London, at the Robert Fraser Gallery, and he asked me if I would like to be body-painted by him. And I said: 'Why not.' (Laughs) Of course it took four hours to do the whole body, and at the end of the day what had been this studio suddenly was opened up for the whole of the tabloid press to come in and photograph and cajole.”

LUST FOR LIFE

“At the time when he was beginning to get more ill, people were really bringing out the knives,” Bill T. Jones says. “It was very hard, very mean, people had been really jealous and resentful of all those nights that Warhol and Basquiat and Keith had enjoyed in the spotlight, or showing up at this or that party and being interviewed in this or that magazine. Some people were gratified that it was all tumbling down.”

“We noticed friends of ours were dying, left, right, and centre,” Fab 5 Freddy recalls. “A lot of people that were gay were very nervous, once they began to realise that it was due to this thing that was largely affecting gay people and the creative community. When Keith found out he was sick with HIV, the virus that led to AIDS, he announced it to the world in a Rolling Stone article (by journalist David Sheff, who also wrote Beautiful Boy, a book on his son’s drug addiction, that was recently adapted for the screen, ks). That was extremely courageous. High-profile people did not do that at the time, and Keith figured: 'I'm gonna lay it out there to expose and inform people about this.'”

Darren Pih: “Keith Haring's work – made over a period of just over ten years – has this vivacity, this energy which seems to be somehow a visual shorthand of America to the world. America at its most optimistic. There is always a terrific sense of energy and movement. Nothing is static, everything is slightly vibrating with potential. His work has a life. Even when he was dealing with issues which are urgent and catastrophic – like the stockpiling of nuclear warheads in the Cold War, Apartheid, or the HIV AIDS crisis –, there was still an optimism and this sort of pop palette and clarity that communicate in a very immediate way. Of course AIDS is the most urgent issue for him, personally, socially, and politically in the 1980s. It affected his own social circle, his friends, but despite this, he still found a way to communicate and to educate and to advocate. He felt and communicated this idea that we need to be open and talk openly about this issue, that we need to act up. I think Keith Haring fundamentally loved life. And that was clear right through the very end of his career, even when he knew his time was short. He just kept on pushing.”

When he became ill, he wanted to get as much work done as humanly possible. Every day was precious

It is a testament not only to his boundless energy, but also his immense generosity. Everyone who knew Keith Haring emphasizes that. “I was helping (legendary cabaret singer and performance artist, ks) John Sex when he became very ill,” vertelt Dany Johnson. “I wanted to do a benefit for him, but he was dead set against the idea, because he didn’t like sentimentality and people feeling sorry for him. So instead, I organized that we would all chip in some money for him. Keith was hanging out with all of those famous people by then, so I didn’t get to see him much. But when I visited him to see what doctor he was seeing – he was already sick himself, but he seemed to be doing better than John – he gave me 3,000 dollars. As it turned out, Keith ended up dying before John. It just shows how much he loved all these people from Club 57, whether he was seeing them all the time or not.”

“After all the partying had died down and many people were getting ill, he stayed a loyal and generous friend,” Bill T. Jones affirms. “When my compagnon Arnie Zane fell ill in 1988, I was living on a dancer's salary. But I could go to Keith and say: 'I'm concerned that Arnie is getting sicker and we don't want to walk down two floors to go to the bathroom. Could you help me buy a new bathroom?' And he would rip 3,200 dollars out of his pockets. He was unique in a way.”

Gil Vazquez, a seventeen-year-old Puerto Rican DJ from Spanish Harlem, likewise shares these memories of Keith Haring, whom he met in 1988 and with whom he remained a close friend in his final years. “When I met Keith, he had already been diagnosed with HIV, but I didn't know. Nor did I know he was gay. I used to work at a T-shirt store near his studio, and Keith – whose subway drawings I had been seeing pop up all over the place – walked in looking for someone else who worked there, an old friend who he knew from the Paradise Garage (another legendary New York discotheque that Keith Haring considered home, ks). Well, my colleague arranged a studio visit and it was eye-opening. I was seventeen and clueless at the time. (Laughs) The only famous artists I knew were dead artists. And here was this guy, surrounded by posters and T-shirts, with his paintings on the wall and prints over there. He was a force of nature.”

“We became really good friends and started travelling together. I think he was interested in showing someone the world, he enjoyed being with somebody who appreciated seeing all of this stuff for the first time. When he became ill, he wanted to get as much work done as humanly possible. Every day was precious. He worked tirelessly until he couldn't anymore. When Keith got sick, it lasted about two to three weeks, and then he was gone. I was there every day, going to get medicine at the 24-hour pharmacy, just trying to be there for him. Every day except for the last one. I think he waited until I took a break one day because he did not want me to see that. When I came back, he was gone.”

“He changed my life,” Gil Vazquez says. “His generosity and his humanity were contagious. It made you want to do good things for other people. Just because. He exposed me. To art and to people like Léger, Warhol, Matisse, Alechinsky, or Yves Klein. But also to the gay community. And with that exposure came empathy. He taught me. He showed me this is my humanity, this is how my humanity is expressed. And it is not wrong, it just is what it is. I think the Keith Haring Foundation (of which Gil Vazquez chairs the board, ks), which he established himself in 1989, is an extension of Keith’s generosity. He wanted to continue to contribute to causes that he cared about, people suffering from HIV AIDS, children’s causes, and the furthering of his own legacy. It was a way for him to be generous beyond his own life.”

Read more about: Expo , Keith Haring , Bozar

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.