450 years after his death, the KBR, the former Royal Library of Belgium, is honouring Pieter Bruegel the Elder with an exhibition of his prints and an homage by one of the greatest and most original muralists in the world: Phlegm. “To walk in Bruegel’s footsteps was a real task.”

Phlegm's take on Luxuria

I miss getting to travel somewhere warm!” Phlegm writes via email when I ask him if, after spending three months making his engraving based on Bruegel’s Luxuria, he misses the physicality of painting the large murals he is most famous for? “But yes, I do feel I miss it. Engraving is very solitary. Long periods of isolation like that aren’t good for you, mentally and physically. It’s good to be aware of that and try to juggle projects so you don’t drive yourself insane.”

Well...let’s allow for a little insanity, the touch of madness that borders on genius. It is at that intersection that Phlegm’s highly unique universe expands. A universe that stretches across walls all over the globe and is characterized by an insane eye for detail, a rigorous use of black and white, and a love of images that start telling stories that stretch far beyond the physical boundaries of the wall. And which refer to each other through his recurring characters: somewhat strange looking, melancholy, almost numbed creatures that wander with covered mouths, a horn ready to attack, or peering through a telescope around an equally imaginative world, warring, surviving, or being pulverized. A world brimming with incredible structures and machines, mythical creatures, and ancient but eternal beings that carry the mythical world on their shoulders, pull the strings, or suffer whatever fate they must suffer.

The earth, in other words. That place where we all attempt to assert our impotent power, conceal our nature, and thunder towards our inevitable end, not least through the things we ourselves create. Like a final fanfare that resounds inaudibly. In this sense, there are many similarities between Phlegm’s world and Bruegel’s universe, where people are cast onto the earth, vacillating between vice and virtue. And just like Bruegel, Phlegm combines his sharp eye with compassion, painful dissection with empathy – we’re all in this together.

MEDIEVAL SURREALISM

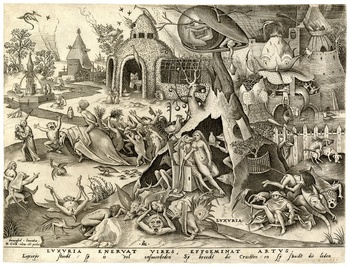

This did not escape the attention of the KBR, when they visited the street art festival The Crystal Ship in Ostend in 2017. The former Royal Library of Belgium promptly asked Phlegm whether he would make a mural to honour Bruegel – that will be inaugurated on 14 October with a rooftop concert – and whether the Welshman would also help to shed light on the lesser-known sides of the creator of iconic paintings like The Fall of Icarus, The Peasant Wedding, The Fall of the Rebel Angels, and Dutch Proverbs who died 450 years ago. “We talked about Bruegel’s engraving in general and Luxuria in particular, of which they own several states of the engraving as well as Bruegel’s preliminary drawing. I spent a long time seeing if my work could adapt enough to feel authentic. Eventually I came up with a composition that I felt worked.”

And three months later you produced an astonishing result. What is most difficult about the process of engraving?

Phlegm: Engraving is like a meditation. I can spend two or three solid days just doing lines that make up the texture of the floor or the gradient of the sky. You have to just try and work confidently and put the hours in without thinking of the whole plate. When you have three months of solid work, to let in thoughts of the result can be crushing. So I guess the hardest part is actually when the end is unavoidably in sight and you know that if you don’t stay calm or you rush, then you could cause a slip that almost destroys the whole thing.

That did not happen, quite the contrary! Your engraving is the final piece in “The World of Bruegel in Black and White”, the impressive exhibition that focuses on Bruegel’s print oeuvre. Do you remember when you first encountered his work?

Phlegm: I have had a long interest in this particular period of art history, and I have always appreciated Bruegel as a wonderful natural painter, someone who was able to have multiple layers of narrative overlapping in his compositions. Certainly some of his more famous paintings of village life packed with dense narrative appealed to me a great deal as a student years ago.

I started as a cartoonist, and I still have graphic novels I’m working away at. So I love narrative. I think I found something fluid and interesting in Bruegel’s sort of medieval surrealism.

Bruegel's Luxuria

Did you know of the engravings?

Phlegm: I’ve come back to his work through engraving, actually, since my work these days is very much related to 16th century copper engraving.

I have always had a strong interest in fine pen and ink work. As I pushed myself to draw with more and more detail, it led me back around to engravers like Albrecht Dürer, Lucas van Leyden, the Wierix brothers, and Bruegel to name just a few favourites.

Seeing Bruegel’s layered scenes and dense compositions rendered as copper engravings is an unbelievable experience. More than anything else, I’d say he was a master of composition. To walk in his footsteps and try to build a picture based on his engraving was a real task.

"Seeing Bruegel's dense compositions rendered as copper engravings is an unbelievable experience. He was a master of composition"

Do you feel a connection with Bruegel?

Phlegm: I feel very connected to this era in history. The explosion of interest in copper engraving and the effects it had on artists of that time feels very similar to my life now and my relationship with the internet. The explosion of printed media and copper engraving suddenly made artists more visible. Prints flowed along trade routes and artists’ work became widespread. I’m a very private person and I feel like the internet fuelled the interest in my work in a similar way.

SNAPSHOTS FROM AN UNTOLD STORY

This tendency to privacy – Phlegm won’t be featuring in portraits any time soon and interviews are rare – has been a lifelong trait, and can explain Phlegm’s love of underground art and self-publishing, the scene in which he started as a cartoonist. He still experiments with his dip pens in the safe confines of his studio and that practice nourishes his mural work. “When I started out I self-published a lot more satirical home-made comics with a very Robert Crumb vibe. Then, as my visual language evolved, the story writing hid in my sketchbooks. I also have a wordless graphic novel I have been working on for over eight years now. It’s still not really more than two thirds finished, even though it’s hundreds of pages long. Comics have always been a part of my practice, they just weren’t visible to anybody.”

Going from comic books to illustration, to a single image must have compelled you to think differently about images?

Phlegm: It has always taken an effort to maintain my relationship with storytelling. In fact, most of my sketchbooks and ideas for murals tend to start as a mixture of frames and written words, short stories or scenes rather than just an image. These stories are kept private in my sketchbooks but then I use a moment from them to create a mural. So hopefully the images seem like snapshots from an untold story. At the very least I think it makes for a more authentic painting.

Phlegm's take on Bruegel's Luxuria

It does make your work very lively in any case. Something hard to pinpoint too, at the same time familiar and elusive.

Phlegm: I think I intentionally try to blur as many boundaries as possible: messing with history and the present, creating characters that seem slightly surreal or creepy, and hinting at complex stories that could have multiple meanings. If you get the mystery right, it’s a sort of catalyst for the observer’s imagination.

Does reducing the scale of an engraving elicit a different imaginary quality for you?

Phlegm: The two scales are actually really similar. Mural work is obviously far more physical, but in both instances, you’re absorbed in the small area you can see. Under a magnifying glass an engraving is reduced to the fairly abstract area you see and it’s the same with a wall. Up close on a huge wall you get no real idea of the thing as a whole. I think I get my buzz from the reveal, working in autopilot and then occasionally stepping back to see it.

Most of the work for my murals is done with no reference, except for the idea that I have in my head and my sketchbook. I rarely take up a sketch in the lift when I work. Since my miniatures project (a book project consisting of 7 by 5-centimetre engraving prints, ks), I often do a very simple line drawing no bigger than a box of matches. That’s enough to remind me of the composition.

It all seems very interconnected. In addition to murals, engravings, and comics, you also make sculptures, like for your recent show “Mausoleum of the Giants” in your hometown Sheffield. Do you think of engraving as a kind of sculpting?

Phlegm: It’s interesting that you say that. I think engraving feels very sculptural. If you look closely at the plates, I’m really carving out the form. I love sculpture because you dominate space. Large-scale murals are the same. It’s architectural and powerful. I think I’ve always approached drawing and engraving in the same way. I’m desperately trying to express the form. The extreme detail is a way of really trying to pull something 2D into a 3D world.

Read more about: Expo , Phlegm , street art , kbr , bruegel

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.