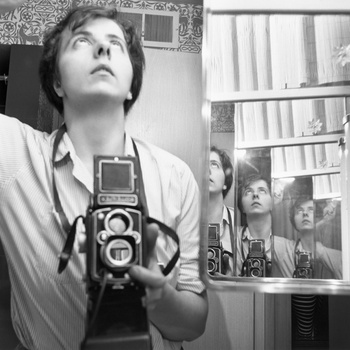

A striking role is reserved for the self-portrait in the unequalled, posthumously unveiled, oeuvre of the American street photographer Vivian Maier. So much so that Bozar is devoting a whole exhibition to it. “It was her way of saying: I exist.”

© Vivian Maier

Who was Vivian Maier?

- Vivian Maier was born in 1926 in New York, her father is Austrian, her mother French

- After her father abandoned the family, her mother’s friend Jeanne Bertrand moves in with them, at that time a well-known portrait photographer. From her, Maier got her love of photography

- After periods in France, Maier returned to the USA, where she started taking street photographs in the 1950s, mainly in New York and Chicago, later travelling around the world. She earns a living as a nanny

- Her artistic practice remained a secret until her work was discovered and unveiled by collector John Maloof after her death in 2009. Maier has posthumously become one of the greatest photographers of the twentieth century

Let's say you take selfies until you drop, but you never, ever, ever make them available to the rest of the world. Would that not be wonderful? That is exactly what Vivian Maier did, an American nanny who took to the streets to shoot images whenever she found the time. Her love of photography was not shared with anyone, however. The families she lived with hardly knew anything about her private life or personal pursuits. Her possessions, including masses of newspapers, books and knickknacks, she kept them safely hidden in her room.

Her private world was only revealed after her death in 2009, when her possessions, stored in a warehouse, were sold at auction. The bulk, some 100,000 to 150,000 negatives of photographs she made somewhere between 1950 and 1994, a few thousand original prints, home videos, audiotapes and junk picked up off the street eventually ended up in the hands of collector John Maloof. He had never heard of the photographer and could find nothing about her online. When he posted some of her photos on Flickr in 2009, a few months after her death, the Internet exploded. Or almost. Maloof really had discovered a treasure.

“Vivian Maier’s photography is an act of resistance against a society that tries to erase everything that does not fit into the American dream”

Since then, Vivian Maier has become one of the most important post-war American photographers, in the wake of like-minded greats such as Robert Frank, Weegee, Helen Levitt and Mary Ellen Mark. Documentaries followed about her mysterious life, including Maloof's Finding Vivian Maier, and her work ended up in galleries and museums worldwide.

Maier is praised for the way she unsuspectingly plucked ordinary mortals and pitiful outcasts from the street scene to immortalise them in the square frame of her expensive Rolleiflex camera. She did this with a sense of framing that could measure up to André Kertész and a timing that was not inferior to that of Henri Cartier-Bresson, not infrequently with an ironic look. “She has a real sense of humour. And a sense of tragedy,” Mary Ellen Mark aptly sums up in Finding Vivian Maier.

Vivian Maier Self-Portrait, Chicago, IL, 1956

The numerous self-portraits that claim a prominent place in her oeuvre are very different: in them, she places composition above emotion. “For Vivian Maier, those self-portraits were a playground,” says Anne Morin, curator of the exhibition “The Self-Portrait and its Double” which can be enjoyed at Bozar from this week on. “She is clearly having fun and is inventing a rich visual language. Her photography is an act of resistance against a society that tries to erase everything that does not fit into the American dream. It shows the periphery, the black hole. But the self-portraits are for me the most fascinating, complex, rich part of her archive.”

What makes these self-portraits so unique?

Anne Morin: No other photographer of the twentieth century has so engrossed themselves in self-portraiture. I think it is partly because Vivian Maier was an amateur. She had developed this practice for herself, and by herself. This visual language has therefore fully retained its freshness. If she at any point had become a professional photographer, maybe she would have been less involved and not in the same way.

Vivian Maier hardly ever had her photos printed, let alone showed them to anyone. Was she not proud of her own artistic practice?

Morin: Photography was her way of relating to the world. It allowed her to meet people, to have “adventures”. To her, the action was more important than the actual image. She did not feel the need to print the pictures, she was immediately occupied with the next image. She had an absolute urge to take stock, to archive. As if she were making some kind of visual encyclopaedia of her time. She was like a hoarder, she continually collected stuff. Her work feels like a sediment of an America that no longer exists.

It was an archive she kept hidden: she never allowed anyone to enter her room in the families where she worked as a nanny.

Morin: Vivian Maier lived by the grace of others. She did have a place with those families, but it was only temporary. That is why her room was so important. That was the only space that belonged to her, where she could build her own universe. It is as Virginia Woolf outlined in her (1929) essay A Room of One's Own: a woman needs her own place, where she can be free, where she can express herself.

“I fit within the frame of the photograph, but do I fit into this world?” Maier's portraits seem to ask.

Morin: That was her great quest, the reason why she went on her photographic odyssey. Vivian Maier wanted to prove that she existed, while society kept her at a distance. Her social status prevented her from blossoming and developing. That is tragic. Her photography is the antithesis of that dented identity. It is her outlet. It was her way of saying: I exist.

“A woman should have an opinion,” you can hear her say in Finding Vivian Maier in an interview she conducted with a woman in a supermarket after the impeachment of Nixon. Why did she not feel the need to speak out?

Morin: I think she was trapped in some kind of determinism. Her mother was a governess, her grandmother was a kitchen help. It was as if she had been predestined by previous generations to play the role of a servant in the shadows. She herself remained within that social perimeter because she did not have the tools or the resources to break out of it. As a professional female photographer, you would have needed a network, a mentor, a fortune, a husband. All things Vivian Maier never had. She started photographing in the early 1950s, in an America where women like her had no voice, they were important but invisible. She was very much up to speed on current affairs, read newspapers and books, went to the cinema and exhibitions, in short, she was a really cultivated woman. She was a feminist, but at the same time she knew her place in society: she was just the nanny.

Vivian Maier Self-Portrait, Chicago, IL, 1956

Thanks to her self-portraits, we know that her looks were somewhat androgynous and that she dressed in robes and hats from an era gone by. What woman do you see in her self-portraits?

Morin: A latent mystery, nothing more. It is a portrait in hollow, it is something that comes to the surface but remains elusive.

Often, all we see in the “self-portrait” is her shadow. A beautiful metaphor for her veiled presence in society.

Morin: The use of the shadow is the most minimal way of saying you are there, but also the most efficient. It is a kind of de-duplication, a reflection of reality without that reality being there. She does not say: look at me, this is how I look. But I am here. This duality is what makes her work so intriguing.

The link with today is easily made: we are addicted to photos of ourselves. The difference being that we immediately share them with the whole world.

Morin: Right now, we are going through a kind of collective identity crisis which Vivian Maier in her own way predicted fifty, sixty years ago. That is why her work is so popular with a generation that is constantly looking at itself in the mirror on Instagram and putting itself in the spotlight on TikTok. Personally, I find this massification terrible, pathetic even. In this globalised world, our identities have become interchangeable. On the other hand, it is fascinating to see how someone who was invisible was able to shine the light on herself. She often used mirrors or reflecting surfaces to depict herself, but there is nothing narcissistic about that. For her, that is just a tool she plays with.

Would Vivian Maier also have been successful if she had decided to exhibit her photos?

Morin: The fact that she kept everything secret and the posthumous discovery of her work have only made it more amazing. But even without that narrative, which is extraordinary, her oeuvre still stands. She has a raw, courageous look on life, and she has nothing to lose. It is fascinating to see how her work lives, develops and matures, and how she, as an amateur photographer no less, has become an icon of photography after her death. That makes her truly unique. For me, Vivian Maier is on the same level as Mary Ellen Mark, Robert Frank and Diane Arbus.

Read more about: Expo , Vivian Maier , Photography , Bozar , Anne Morin