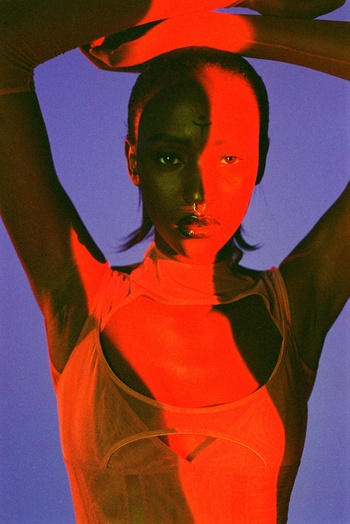

Following Stromae and Angèle, Brussels has again produced a ready-made international pop sensation: Lous and the Yakuza. Five years ago, she was broke and living on the street. Now the singer of Congolese and Rwandan heritage is the next big thing. “I’m doing this to give all those young black women out there an example and to show that they can make a difference.”

© rv

| Lous and the Yakuza

Also read: Brusselaars sterk vertegenwoordigd in Belgische '30 under 30'-lijst van zakenbijbel Forbes

For Lous and the Yakuza, all of the puzzle pieces fall into place on their album debut Gore. With a contemporary, idiosyncratic style that blends trap and R&B with clever pop structures and even a dash of classical music, which her father taught her to love as a child. But above all, with a very assertive attitude that is intended to inspire a generation of young black women to follow in her footsteps. In her intriguing music videos, she consistently reverses social roles.

In “Amigo”, she intentionally does not kiss the frog because she does not want to have to deal with any princessy nonsense. She does not live in a fairy-tale, though to the outside world it does have all the appearance of one. After an extraordinary reversal of fortune in her life, her career is now in the ascendant. The songs that she released over the past year caught on. From Africa to America, where Madonna’s children imitated her dance moves for all the world to see. She was given a contract as the face of Louis Vuitton and was recently invited to present her new single on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. And these are only the visible aspects. Behind the scenes, she has now also designed a coworking space in the Northern Quarter of Brussels and she is supporting a Rwandan government project to build more hospitals.

© Lee Wei Swee

| Lous and the Yakuza: Gore

When we meet the artistic jill-of-all-trades at the offices of her Brussels PR agency Five Oh, she is dressed casually, though clothing can be both a weapon and armour for her, as she recently said. “I’m in a laidback mood today,” she reassures us. “But tomorrow that might shift to a no-fear mood. My fashion is a way to send a message before I have opened my mouth.” When she is later served a plate of sausage and mash, her face lights up completely. “My Belgian side,” she laughs. “I’m addicted to it, man!” During our lunch, she tells her life story, which at certain points was so hardcore that it became almost absurd. “To some extent, that insight was my salvation. It helped me to climb out of the abyss.”

A STAR OVER LOUISE

Flashback to one of the darkest nights in December 2015. Marie-Pierra Kakoma – the name on the singer’s birth certificate – has been homeless for a while and is wandering around the Louiza/Louise neighbourhood at night. Utterly desperate, she starts weeping. As she cries, she looks up at the sky and despite all the light pollution, she sees a star shining. The surprise makes her laugh uncontrollably. “Oh my god,” she thinks. “How the hell did I end up here?” She replays the film of the past few months. She’s nineteen, a world star in the making, but she doesn’t know it for sure yet. Her parents, both doctors, had envisioned a very different life for her. She rebelled.

I was always a strange child. For as long as I can remember, I have heard my mother saying at family parties: “Who gave me this weird child?”

Fortunately there is still music. Her mobile is usually switched off, but during the day she charges it at train and metro stations, so that she can watch YouTube or download songs. “In that period, I was mostly listening to the Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto and his soundtrack to Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence (a 1983 film about a Japanese prisoner of war camp on Java, starring David Bowie and Sakamoto himself, Ed.). It was the perfect soundtrack to that miserable Christmas... I think I started laughing so uncontrollably because it was a way of triggering and activating happiness and positivity.”

The striking thing about Gore is that the album is entirely about the tragedies in Kakoma’s life, but that at the same time, it has such an infectious, contemporary and melodious pop sound that it is impossible to sit still while listening to it. As though by repeating the shit over and over again through the verses and refrains, Kakoma is actually allaying the misery. “I often asked my producer (El Guincho, the man behind Rosalía’s mega success El mal querer,Ed.) if this is really pop, because the background is so dark. ‘Yes,’ he would always answer decisively. It is in the structure, in all the bridges, the pre hooks and the choruses I love so much. And even though there are no love songs on the record, there’s a will to love in all the songs. They are about how much I missed love, about how at a certain point I even hated it, and about how much I needed to be loved.”

It must be an enormous relief finally to release your debut album.

Marie-Pierra Kakoma: Yes, it took such a long time that I can hardly believe that I am now officially an artist and not just an idea. The crazy thing is that I knew my songs were quite popular online, but because of corona, I wasn’t touring and meeting my fans face to face, that had just become an idea. There were only statistics to keep me going, but they blew me away.

When I first heard your debut single “Dilemme” on the radio last year, I immediately wondered: “Who is this?”

Kakoma: I’m happy to hear that, and you were not the only one. In Italy, I topped the ranking of most Shazamed songs. It’s the charts that make me happiest actually, because they are purely about the music, not your face or the music videos. It means that the music is arousing curiosity (To date, “Dilemme” has been Shazamed over 425,000 times, Ed.). The first thing I told my producer is that I wanted to create my own sound, just like artists such as FKA Twigs, James Blake, or Stromae. Not only because I want people to be able to recognize me, but also because I want my message to hit home. Contrary to many of the artists who are currently high up in the Spotify charts, I think lyrics are very important.

If you’ve ever been broke you never want to go back there. Now that I am on the other side, I can dream bigger dreams and focus entirely on my art

Did you learn anything from being broke that you can apply now that things are going so well?

Kakoma: Only that if you’ve ever been broke you never want to go back there...because it is dehumanizing. At a certain point I was so broke that I couldn’t even afford to buy food or sanitary towels. Fortunately, I managed to find solutions over time. Street ghetto solutions, but solutions nonetheless. Ultimately, it is not the money that you miss, but the food and the roof over your head. The song “Dans la hess” is about that period. Hess is common slang in Brussels. It comes from Arabic and means misery. I sing that I will seize every opportunity to climb out of the hole, though I felt that other people in the hood resented me for it. Now that I am on the other side, I can dream bigger dreams and focus entirely on my art.

Was the ability to stretch your artistic wings not the reason why you moved back to Brussels when you were fifteen?

Kakoma: I just wanted access to art, which I did not have in Rwanda at all. When I spoke to my parents about it, their reaction was: “Are you mad? You’re fourteen!” But I wanted to paint, record music, own a guitar, and play the piano. All of those things were impossible in my motherland. I kept badgering them until, a year later, they finally relented. Yes, I was always a strange child. For as long as I can remember, I have heard my mother saying at family parties: “Who gave me this weird child?” I wrote a song about it when I was fifteen. Now, it must be said that I did interrupt every single family party to recite my poetry. I would stand up, cough a little, and ask – rhetorically – “May I recite the poem I composed for daddy?” When I saw everyone looking at me, thinking “What? You are eight, bro!”, I would cough again and launch right into it. After my poetry I would often also sing an a-cappella version of the “Ave Maria”, in Latin! That’s how much of a weirdo I was. Every aunt and uncle in Rwanda commiserated with my parents. They would always be told: “We are so sorry for you!” (Laughs)

© Lee Wei Swee

| Lous and the Yakuza: Gore

You returned to Brussels as a teenager, but you had lived here as a child. What were your impressions when you arrived here as a four-year-old?

Kakoma: That it was so cold! I also remember the first time I saw snow. I was blown away by that ice that was coming from the sky. We lived in Sint-Joost/Saint-Josse. I was still very ghetto. Everyone was poor, even the white people. But I felt very welcome. All the neighbours knew one another and we would laugh a lot. I played with African, Arab, and Belgian children and I loved that mix. When I came back as a fifteen-year-old it was very different. I went to a boarding school and it was the first time that I experienced a new kind of racism, which was directed purely from white people to people of colour.

I had been discriminated against in Africa too. In Rwanda because I was half Congolese. In Congo because I was half Rwandan. Those two countries have hated each other since the war started in 1996. When I was two, my mother was gaoled in Congo because she was Rwandan (the reason the family fled to Belgium in the first place, Ed.). But in the six years that I went to the Belgian school in the Rwandan capital of Kigali, nobody was ever mean to me because of the colour of my skin. On the contrary, I had many white friends. When I returned to Belgium, I was shocked by the ignorance.

Are your music and your music videos a way to combat that ignorance and stereotyping?

Kakoma: Yes, but also more than that. I need that diversity, and I insist that everyone I work with adapts to it. I work with a lot of black people because others won’t and it ensures they have an income, but also because I hope it will inspire other people to do the same. At the same time, I want to represent black men in a different way than normally happens. We’re still living with the prejudice that they are dealers, criminals, and violent, and that is not true! Yes, some are, but so are some white, Asian, or Latino people.

In the music video to “Amigo”, I have a single black women be loved and celebrated by a handful of virile black men. It is a message to the black community itself. Too often I hear my friends say that they would never go out with a black woman, especially if she is very dark-skinned. What the fuck? You don’t pick people because of their race. When you fall in love, you fall in love. Full stop. By choosing a very dark-skinned woman for the music video, I wanted to add a positive and strong image to my own culture, which needs such representations.

You don’t pick people because of their race. When you fall in love, you fall in love. Full stop.

When you strive to be an example, it is not only important to talk, but also to take action. That is the only way that you can inspire young people. When I started collaborating with the Rwandan Ministry of Healthcare last year, to campaign for the building of new hospitals, I was only 23. I want people to know that and think: “Oh my god, even at 23 you can effect change!” As doctors, my parents are closely involved in public health in Rwanda and Congo. So I knew most about that and it was the best way I could help to make a difference.

And so at 24, it seems that Marie-Pierra Kakoma has come full circle for the first time. Not with a doctor’s coat on her slender body, like her parents would at first have wanted, but in an LV suit and a voice that resounds with resilience in the international spotlights.

LOUS AND THE YAKUZA: GORE

Released through Columbia/Sony

Read more about: Muziek , lous and the yakuza , Gore , Marie-Pierra Kakoma

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.