Germaine Acogny has been called the grande dame, and even the founder, of contemporary African dance. Over a long career with many international collaborations she also founded the Ecole des Sables near Dakar, the most important dance school on the African continent. With the tour of Somewhere at the Beginning, the choreographer and dancer is once again coming to Brussels, a city she has strong ties to.

© Thomas Dorn

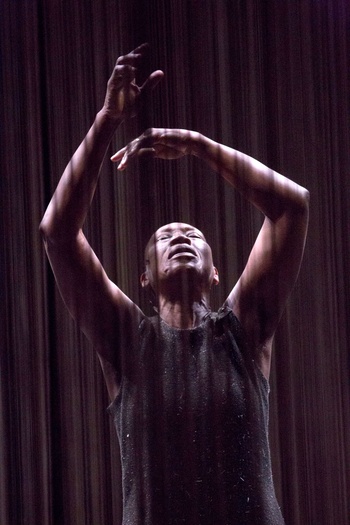

| Germaine Acogny is 77 years old but does not think about stopping. “We have been playing this piece for five years now and I hope we can play it for years to come.”

Germaine Acogny was awarded the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale last year. But that was by no means her first award. She has been knighted in both Senegal and France and received several dance awards, including a Bessie Award. Acogny was born in Benin in 1944, but has lived in Senegal and around the world since she was ten. When she was young, she regularly visited Europe when accompanying her father, the diplomat Togoun Servais Acogny. But she kept shuttling between Senegal and especially Europe also once she started dancing in 1968.

Brussels has always played an important role in her life and work. Germaine Acogny: “Léopold Senghor (president from 1960 to 1980, ed.) wanted to make Senegal the ‘Ancient Greece’ of Africa by promoting literature and other classical arts. He came to see me because he had no structure for contemporary dance and he wanted to introduce me to Maurice Béjart (French choreographer of the Ballet du XXe siècle and the Mudra dance school in Brussels, ed.). Béjart too had Senegalese blood and was a friend of Senghor. When King Baudouin invited Senghor in 1965, he brought me along with him. I then gave a class at Mudra, where I also met Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker and other dancers. Maurice saw that I had something new to offer and in the end, he chose to base Mudra Afrique in Senegal in 1977, with me as artistic director. Once Senghor was gone, Mudra Afrique had to close its doors. But then I met my current husband Helmut Vogt and we first founded the Studio-Ecole-Ballet-Théâtre du 3e Monde in Toulouse in 1985, and from 1998 the Ecole des Sables, and then shortly afterwards our company Jant-Bi.”

The bond with Brussels, and also with Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, has always remained. Acogny: “Certainly. There is a strong link between P.A.R.T.S. and L’Ecole des Sables. We have regular exchanges with dancers and workshops. Returning to Brussels always makes me happy. I lived on Zelfbestuursstraat/Rue de l’Autonomie, and in 1985 I got married at the town hall in Anderlecht. I never danced with the Ballet du XXe siècle, but I did work with them. You know, I was once on the Grote Markt/Grand Place with Maurice Béjart and I rubbed the arm of the statue of Everaard t’Serclaes to make sure that my wishes would come true. And that is what happened.”

The serpent of life

We are also familiar with the co-director of the Ecole des Sables in the coastal town of Toubab Dialaw, south of Dakar, because since 2020 that is the choreographer, dancer and teacher Alesandra Seutin from Brussels. “She took my technique classes here and is a real ‘Sabliste’ as we call it. Helmut and I are the founders of the school but we are now passing the torch to the younger generation while I continue to dance. Just like Wesley Ruzibiza, Alesandra is close to me. Their vision is to continue on the right path and lead the school into the future. I hope we will see her again in Brussels during the pre-and post-conference talks on Sunday.”

Acogny’s technique has several components. Nature already plays an important role in it. This is also reflected in the infrastructure of the Ecole des Sables, where the studios blend into nature, and rehearsals can in part take place outside. “My husband Helmut is not an architect but he loves architecture. Dance is always inspired and influenced by its surroundings. People who live by the sea do not dance in the same way as people who live by the woods, urban dance is adapted to the cities and that is why there is not a single studio here that is not oriented towards nature. The bungalows also face the lagoon and the baobab, even though that nature is now threatened by the construction plans for a container port that we oppose.”

If Acogny uses metaphors from nature such as the water lily, the baobab and the starfish for her dance, it is also because her technique is distinguished on a physical level by the attention paid to the spine. “The spinal column is the serpent of life, the tree of life. People are not always aware of their spine, but that is where movement starts. If my technique is so successful in the world, alongside those of masters such as Martha Graham, José Limón and Merce Cunningham, it is because it adds something to the way we move. It also helps you feel better mentally because if the physical side works, the mental follows.”

There is a saying that one’s sweat never goes to waste. I have sweated, and now I reap the rewards of having educated and helped people in different places in their lives

Acogny’s dancing can this week be seen again at Kaaitheater, where, as part of the Moussem Cities Dakar festival, Somewhere at the Beginning/A un endroit du début is on the programme, a creation with director Mikaël Serre. Acogny: “Someone said to me recently: ‘Maman Germaine, most people are very active in the first part of their lives, and then they look back at what they have done. While are you still busy at 77?’ Well, I also feel that this is when I am benefiting from life. In the past, I spent a lot of time teaching and passing on my technique. There is a saying that one’s sweat never goes to waste. I have sweated, and now I reap the rewards of having educated and helped people in different places in their lives. As long as I have the strength to dance, I will continue to do so. I have some arthritis in my knee, but you have to come and see for yourself how I do physically. We have been playing this piece for five years now and I hope we can play it for years to come, also because it is a relevant performance. The creation contains elements of personal stories that are universal: it is about the position of women, tradition and emancipation, roots, identity and the fact that if people respected their different identities, there would be less war and conflict.”

When the migrant becomes king

Somewhere at the Beginning contains many personal stories, including those of Acogny’s family which come to us through her father and grandmother. Grandmother Aloopho was a priestess of the Yoruba people, and practised animism. Her father lived in a completely different context. He was an ‘Enarque’ (graduate of the French École nationale d’administration (ENA), ed.) and became an ambassador to several Western cities. “He was also a poet and wrote about his youth so that his children would know their past. For this piece, I drew on my father’s writings and my grandmother’s stories. Like adults in Europe do when they tell fairy tales as a way of educating children. One of Grandmother Aloopho’s stories was about migration, because people have always moved around. Tiviglititi was a wise man who was taken by a king to his palace. This made the king’s advisers jealous, and they had the sage thrown into the sea in a coffin. After travelling across the sea, the coffin ended up in a foreign land where the king had just died. Tiviglititi told his story to the people without a king and was immediately made the new king. Because in that country, the honour of becoming king was reserved not for people born there but for those with an exceptional life story. When the king and the counsellors from Tiviglititi’s native land were invited to his coronation, they were astonished to learn that he was to become the new king there. Then Tiviglititi spoke: ‘Now you understand that you can know where you were born, but you cannot know where you will die.’ For me, that is the story of Barack Obama, but also of other people who can take up leading positions in other countries.”

In addition, Somewhere at the Beginning has other themes, such as religion. “When my father was colonised, my grandmother asked him not to convert, because Christianity would not bring him anything new. The Christians brought the holy water but water is sacred in animism too. For us the python is a sacred animal, while in Christianity it plays a role as the tempter of Eve and a symbol of the Devil.”

© Thomas Dorn

Director Mikaël Serre brought in the Medea story of Western culture. “When he read me that story, I immediately said that it is about the lives of many women today. About polygamy and men’s mistresses, which women still fight against. It is also my story.”

Along with Acogny’s dance, for which her son Patrick Acogny worked with her as a choreographer, there is also video by Sebastien Dupouey and music by composer Fabrice Bouillon. “Mikaël Serre brings this overall spectacle together like an orchestral master. He works in a disciplined way and he composes, but within the structure he also gave me a lot of freedom to develop my choreography through improvisation.”

Read more about: Podium , Events & Festivals , Germaine Acogny , Dakar , Moussem Cities , école des sables , Alesandra Seutin , Maurice Béjart