Photographer Joel Meyerowitz is best known for his epic photos of Ground Zero. But above all, he is a pioneer of street and colour photography. “All I knew was that I wanted to be out on the street where everybody else was so I could watch humanity doing its crazy dance every day.”

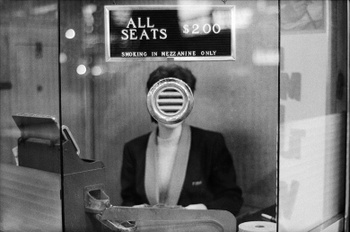

© Joel Meyerowitz New York 1975 courtesy Polka Galerie

It would bore the shit out of me if I were to take the same picture again and again,” Joel Meyerowitz answers laconically when we remind him of his rich and varied career via Skype. He is 79, but age does not seem to affect the photographer from the Bronx at all. His tanned skin betrays a life of outdoor photography, and his clear and searching eyes indicate sharp vision. Four years ago, he and his wife Maggie Barrett left America to settle in rural Tuscany. After street photography on 5th Avenue, landscapes with big-format cameras in the soft natural light of Cape Cod, portraits of redheads, and epic photos of Ground Zero – as the only photographer with regular access to the ruins of the 9/11 attacks –, in his new home he is now focusing on still lives.

Meyerowitz: “A couple of years ago I visited Cézanne’s studio in Aix-en-Provence. Once I went into the studio I had one of those unexpected reactions to an object which caused me to think about things in a fresh way. After the visit, I started to make still lives; not in a conventional sense but to examine the photographic nature of still life as such. Throughout my career, every six or seven years, a new question about photography came up. That question often turned my path from straight ahead to a new direction. This curiosity about the way photography works has been the guiding principle of my career. I look at a number of my peers and they have been taking the same picture for fifty years. It makes me wonder whether they don’t have any other ideas and whether anything else interests them. It’s like saying the same thing over and over again.”

© Joel Meyerowitz, New York, 1963, courtesy Polka Galerie

The beginning of his career was marked by a similar sort of epiphany. With a degree in fine arts – majoring in painting – he began as an art director in 1962. Overseeing a shoot in downtown Manhattan, lightning suddenly struck. “My boss had hired Robert Frank [one of the most influential photographers of all time, who revolutionised the medium with his photobook The Americans (1958) – HR] for the job. I knew nothing about photography except that you always had to say stop, hold that pose, lift your chin, hold the action. But here was Robert Frank who moved around and took photographs in the same moment. Watching him work swept me away. It was so awesome to me that I immediately quit my job, borrowed a camera, and went out on the streets of New York. I’ve been a photographer ever since.”

So the trigger for you was the action itself, seeing a professional photographer – the legendary Robert Frank – at work?

Joel Meyerowitz: Exactly. As a painter, I was used to moving around the space physically when I painted. The idea that this kind of physicality, this dancing was part of photography became my motivation to start out as a photographer. I had no idea what photography looked like. I had only seen pictures in LIFE magazine, war pictures, or portraits of famous people. It wasn’t something I was interested in at all. But the idea that you could intercept the dance of life with a camera and hold it in a fraction of a second fascinated me.

Perhaps it was an advantage that you didn’t know anything about photography beforehand.

Meyerowitz: I believe it was exactly that. I had no prejudice either way. I didn’t think I should make interior photos, landscapes, or portraits. All I knew was that I wanted to be out on the street where everybody else was so I could watch humanity doing its crazy dance every day. After I left Robert Frank’s shoot, everything I saw on the street looked different. A bit like leaving the movie theatre after watching a film by Wim Wenders or Federico Fellini. You go out into the world and suddenly everything looks fresh to you because of what you saw in the movie.

After Frank’s photoshoot, I realized that the gesture of moments and the interrelationships between things were my subject. I realized that perception was what photography was all about. Not style. And of course colour! From my first moments as a photographer I worked in colour and I believed in its potential. Why wouldn’t I? The world was in colour!

© Joel Meyerowitz, courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallerie

| At Ground Zero: “What followed the tragedy was full of life. There were thousands of people there working, searching for survivors, and trying to rebuild, to recover. That’s a very powerful and positive human response.”

When I look at your pictures there is always this joy, if I can call it that. It’s not the grim side of New York that we see. It’s the pleasure of walking around and seeing all these interactions.

Meyerowitz: That is not something that I am consciously trying to make happen. It’s the nature of each of our individual responses. I know quite a number of photographers whose view of the world is darker. They are always looking at the underbelly. Looking at the people who are down and out. Looking at the destroyed, people who are enslaved, or abused, or living in squalor. Maybe they want to do something helpful with that. But the ordinary human condition is the combination of both.

When I put a frame around a moment in time, all the things in the frame in relationship to each other make the photograph. It’s not only about a happy person smiling or a sad person carrying all their belongings in a plastic bag. It’s about the two things, or the four things happening at the same time. That’s how complex our modern lives are. I think of myself for the most part as someone who is trying to describe urban life, and all of its mixture and its ups and downs. And to have some sense of its unpredictable quality.

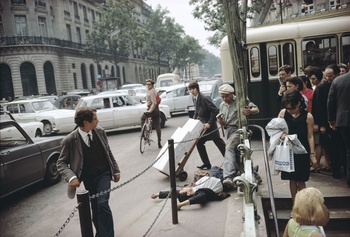

© Joel Meyerowitz, Paris, France, 1967 Courtesy Polka Galerie Paris

| Paris through the lens of Joel Meyerowitz: “When I put a frame around a moment in time, all the things in the frame in relationship to each other make the photograph.”

So you are quite the optimist? You even call photography an optimistic sport.

Meyerowitz: [Laughs] I think everybody serves their own personality through the art that they make. Yes, I’m an optimistic person in general. I believe that most people are good. I believe that things will work out for the best. I’m probably a foolish optimist sometimes. But nonetheless, the things I see out there always excite me. When I press the button on the camera I still have this “Oh yes, that’s the one” feeling! The human condition seems to affirm itself in the pictures I make, whether they are humorous or sentimental or uplifting. And you know, I also just followed that inner life of my own.

As a foolish optimist it must have been hard to photograph Ground Zero?

Meyerowitz: When I was working inside Ground Zero after the Twin Towers collapsed, many people said to me: “Oh Joel, you should be using black and white.” I thought that was crazy. Why would I be using black and white? That would cast the whole thing in a tragic mode. And the tragedy had already happened. What followed the tragedy was full of life. There were thousands of people there working, searching for survivors, and trying to rebuild, to recover. When you see other human beings doing acts of kindness and devotion, when you see them on their hands and knees scraping the dirt looking for the dead, looking to identify people, that’s a very powerful and positive human response. And then a beam of sunlight falls on it on a beautiful fall afternoon. Leaves blowing and birds flying. And you think, oh my God, life goes on, even in the face of tragedy. So I took the positive aspect from that. There was a very positive spirit. Losses heal through time and through nature’s positivity and so I couldn’t imagine myself retaining the tragic point of view.

You moved to the Tuscan countryside a few years ago. As a native New Yorker, don’t you miss the bustle of the city?

Meyerowitz: I always liked the feeling of crowds because in crowds you can always see many things at the same time, but in a way, I like retreating to this countryside so I can go back to the city with a fresh perspective. I’ve been in Paris lately, I'll go to Berlin soon, I come to Brussels, I go to London regularly… I’m very physically active and I feel fit and youthful. I think photography keeps me young but certainly living in the countryside is not like walking down 5th Avenue every day. And I have to be honest, when I was 30 or 40, I had a different presence on the streets. The image that I project now when I’m carrying a camera is not the one of that young guy who could get away with almost anything. So in a way I have to deal with the new impression that I give.

Is it more difficult to blend in?

Meyerowitz: The subjects of my pictures are different. First of all, our time is different. We live in the age of the smartphone and everybody looks different because they are walking along and typing, photographing, or talking. People don’t relate to each other in the humanistic way that they did in the 1960s, ’70s, ’80s, or ’90s. That’s a lot of time. People are more suspicious now, afraid that their image will be used on the internet in a way that will be negative for them.

Nowadays it’s difficult to photograph somebody without a device that isn’t glowing.

Meyerowitz: That’s right. You see it in New York now on 5th Avenue. If there are twenty people in the picture, fifteen of them will have their phone up. So you see a different kind of humanity. The underlying problems in this period of time – with the internet – is that people feel their image has value. Whereas when I first started, nobody could imagine being photographed. I remember every time I would lift the camera to take a picture, people would – if they saw me, which most of the time they didn’t – look behind them to see what it was that I was interested in. They couldn’t imagine that I was interested in them. I’ve known both periods but for people growing up today, they only know the present and its cult of personality. They have to deal with this new idea of celebrity which is a big part of what the ordinary person thinks about. They want to be instant celebrities. I sometimes hear people being interviewed and when someone asks what they want to be, they say: “I want to be famous.” But for what?

But hey, times do change. And photography has always advanced through technology. Always, from the very beginning. So why say no to it? I have had a computer since 1976: the first Apple. The very first computers that Steve Jobs made had no serial numbers, and I have one of those. I started using Photoshop immediately when it came out in the early 1990s, believe it or not. And I was one of the first people to use digital cameras in 1999. I always had a strong sense of the technological turnover and you know, it’s unstoppable.

> JOEL MEYEROWITZ: WHERE I FIND MYSELF. 14/12 > 28/1, Botanique, www.botanique.be

Read more about: Sint-Joost-ten-Node , Expo , Joel Meyerowitz , fotografie , Ground Zero

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.