From her bathroom studio, Azam Masoumzadeh commutes between the sublunar and the sublime, thousand-year-old poetry and new technologies, Iranian miniatures and stories larger than life. Her moving travel account, Glad That I Came, Not Sorry to Depart, is the first Belgian comic with augmented reality.

© Ivan Put

WHO IS AZAM MASOUMZADEH?

Born in Isfahan, Iran in 1989.

Grows up surrounded by the thousand-year-old philosophical poems of Omar Khayyam.

At 18, after having drawn all her life and leaving high school with a diploma in painting, goes to study textile design in Tehran.

Moves to Brussels in 2012, to study illustration and comics at LUCA School of Arts,narration at l’ERG, and digital art at KASK in Ghent.

Glad That I Came, Not Sorry to Depart is one of the first projects of the InnovationLab of the Flanders Audiovisual Fund and receives a Special Mention at the Anima Festival in 2020.

At the end of 2020, she publishes her book of the same name, the first Belgian comic book with augmented reality, now going into its second print.

“As a child, I often heard my mother recite a poem while she was doing the housework. Whispering, almost inaudible.” The first words of Glad That I Came, Not Sorry to Depart open up a sensitive, almost magical space, as the Iranian-born, Brussels-based artist Azam Masoumzadeh explains how that poem crept under her skin over the years and became a companion. First as a melody she could not shake off. Only later, when its meaning became fully understood, as a guide to life.

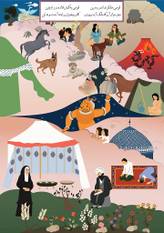

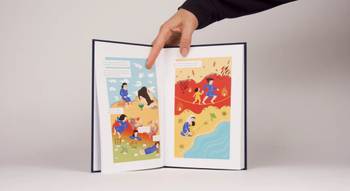

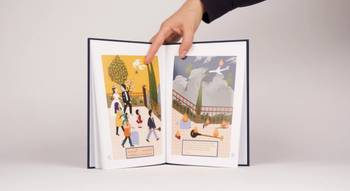

With Glad That I Came, Not Sorry to Depart that poem now travels from a house in Isfahan to eager Brussels ears. “Alike for those who for today prepare, and those that after a tomorrow stare, a muezzin from the Tower of Darkness cries ‘Fools! Your reward is neither here nor there!’” echo the words not only from the paper, but also in Azam Masoumzadeh's soft, sweet voice – thanks to the augmented reality that allows you to bring ten illustrations and as many short poems from the book to life with the help of an app. The drawings, inspired by Iranian miniatures – “these two-dimensional illustrations and paintings I grew up with and that somehow made sure that I still suck at perspective” – moving as only miniatures can: slow and a bit stately, able to move heaven and earth.

© Ivan Put

But at least as tempting is the Farsi that you will hear, the language in which Omar Khayyam's poems were set down almost a thousand years ago. “I miss the language,” Azam Masoumzadeh says just after she has fought for half an hour with her pillows – “Mondays are monsters!” – which try to keep her in bed with their soft but compelling hugs. “I miss speaking Farsi, and the particular accent and way that people talk in Isfahan, the city where I grew up. Sometimes my throat yearns to pronounce those specific sounds. Then again, if I were to return to Iran, I would miss speaking bad English – which I’m fluent in. (Laughs) I like to switch between languages, depending on the character of the words, on how heavy they weigh in different tongues. I recycle mentalities and cultures.”

Maybe it was in imagining that movement, the disappearance of the moon, the passing of life, this constant coming and going, that I saw the added value of augmented reality. To go beyond the silent, unmoving paper and make that change tangible

Azam Masoumzadeh is an in-betweener. Between languages and between artistic disciplines like painting, textile design – “which I don’t practice anymore” –, illustration, comic books and digital art. But also by nature, as an Iranian, “between East and West, between believing and not believing, between being earthy and being spiritual. Life becomes easy when you accept this state of being in between things. Though it can be hard as well. It is a lot of work to keep your balance when manoeuvring between two extremes and trying not to fall into one or the other. Extreme thinking does not doubt. It provides easy answers that uncertainty cannot give us. Being in between is dealing with a bunch of questions all the time.”

CHILDREN OF THE REVOLUTION

“It is about accepting and knowing that you don’t have a clue,” Azam Masoumzadeh continues. That philosophical truth, derived from the Rubaiyat, a collection of four-line poems by Omar Khayyam, runs like a thread through her life. “I used to say I came to Brussels because of comics, but that is a lie. (Laughs) I wasn’t that thoughtful at 22. You know, I only applied for one university abroad, and that was LUCA School of Arts in Brussels. They accepted me, and I came. So there weren’t that many thoughts and considerations behind it, I’m afraid. If you ask a drunk person how they got from the bar to their home, they’ll admit that they have no clue but that it probably won’t have been easy. Well, that’s me coming to Brussels. (Laughs) Every path I have taken, from painting and doing textile design in Iran to studying comics at LUCA, narration at l’ERG and digital art at KASK, was a path I stumbled onto. I went with the flow of life. Inevitably you make mistakes, but good things come out of it too.”

That is the least you can say. In that temporary final stop which is Brussels, Azam Masoumzadeh has set up her studio in her bathroom – “Well, you make do with what you have, right?” – in a house she shares with a few other residents. Her drawings adorn the white tiled walls, while the water heater and the lamp above the washbasin have been given a broad smile with a few strokes. “I rarely take baths,” she says teasingly, “it ruins my artworks. So I just stay dirty!” (Laughs)

Dirty or not, her Glad That I Came, Not Sorry to Depart, one of the first projects of the InnovationLab of the Flanders Audiovisual Fund, did get her a Special Mention at the Anima Festival in 2020. The book that she produced from that digital art project – “as far as I know, the first Belgian comic with augmented reality” – is now in its second printing. This is not only due to its innovative character. Glad That I Came, Not Sorry to Depart is also a tangible focal point in which artistic identities, thousand-year-old writings and new technologies converge. But most precious of all: it is the heart of a story that unflinchingly but tenderly crystallizes between Azam Masoumzadeh and her mother.

What do we know? We all struggle most of the time, we all fuck up. That’s okay. Just don’t judge too hastily, be nice!

“It is not the story of all Iranians, it is our story, the story of my family, of my mother,” Azam Masoumzadeh emphasizes. Of how her mother balanced between heaven and hell, doubt and conviction. How, as an only child, she lost her mother when she was ten and married seven years later. How at that moment the Islamic revolution broke out, and she felt herself straitjacketed, forced by society to be radical in her way of living and thinking. How, for the young woman who had appropriated literature, the thousand-year-old poetry of Omar Khayyam became a refuge, a guide. And a confrontation.

© Ivan Put

“It was about the only thing my mother could read. Books ended up on the blacklist, the poems of Forough Farrokhzad – the first female Iranian poet to talk about femininity and sexuality, passion and love – that were so precious to her, were censored. Society transformed into this very conservative, religious context, where reading such things were not seen as fitting for a girl who just got married. So she struggled. It’s what I remember from my childhood: that I saw my mother cry, that I saw her fall and recover, shuffle between that daily life she led – with me and my two older sisters, constantly in the company of her in-laws, without education, disconnected from art – and the promise of poetry. So yeah, the revolution really affected my mother's life, on so many levels. (Grows silent) And it still reverberates today…on me.”

NEW MOON

“Then again, this struggle only represents ten percent of my mother's character. It’s not all she was,” Azam Masoumzadeh adds. “When you’re narrating a story, telling it over and over again in your head, after a while reality and imagination get mixed up. So yes, I was nervous when reading it to her, afraid that she would say that my ‘reality’ was totally distorted. But she just cried, said that it was exactly how she had felt those days and that she was so happy that I had talked about it.”

My mother struggled. It’s what I remember from my childhood: that I saw her cry, that I saw her fall and recover, shuffle between that daily life she led and the promise of poetry

At an unfathomable depth, undoubtedly unspoken words are still searching for the right Persian sounds. But apart from that intimate, undigested knot, there is also a remarkable, almost primal strength in the young soul of Azam Masoumzadeh. A force that succeeds in bridging the gap between a thousand years ago and the present day, because it feels the pulse of man beyond time and place. “In that sense,” Azam Masoumzadeh stresses, “this is not a political book, nor is it only about my mother.” It’s about all of us, faced with this whimsical and wonderful thing called life. “You know what appeals to me in the poetry of Omar Khayyam? His call to live this life full of uncertainty and doubt with dignity, to take life seriously – because it is serious – but also to laugh about it. That is the art of life.”

Embracing the unbearable lightness of being. “I think that that sometimes very dark sense of humour is very much ingrained in Iranian mentality. It’s laughing with misery. With all of these catastrophic things happening around them, and all of the possible ways to deal with them, they choose to make jokes and laugh.” That humour bites and liberates, and is a lesson in times when the human view of the world – as manageable, moving according to our will – is accompanied by a certain arrogance. “Never forget that nothing is certain and nothing stays the same,” Azam Masoumzadeh’s mother advised her when she left Isfahan to go and study in Tehran. “Maybe it was in imagining that movement, the disappearance of the moon, the passing of life, this constant coming and going, that I saw the added value of augmented reality. To go beyond the silent, unmoving paper and make that change tangible.”

© Ivan Put

| Azam Masoumzadeh in her bathroom studio: “I used to say I came to Brussels because of comics, but that is a lie. I just went with the flow of life.”

If anything is certain, it is that coming and going, and the irrevocable end. “For the rest, what do we know?” Azam Masoumzadeh says. “That realisation fills you with humility. This book, these moments I spent piecing together my mother’s history, have been therapeutic. I always knew she was lost, she still is sometimes, and that’s fine, but knowing why she was lost, has helped me a lot. If you put everything together, it makes sense that my mother was who she was, and that it went the way it went. So I’m not harsh on her, nor my father. He got a bit disconnected from his daughters along the way, but he has been on my side whenever I needed him. You know when you ride the tram, at a certain moment the tram driver gets out and changes the tracks? Well, we never had very deep conversations on board, but my father did change the tracks for me a lot, and I really love him. (Smiles gently) We all struggle most of the time, we all fuck up. That’s okay. Just don't judge too hastily, be nice!”

“I, too, sometimes see life as a long and strong snake that sneaks up on me and then swallows me up,” the end of Glad That I Came, Not Sorry to Depart reads. “What counts in the end is the sum of the glasses of wine I drink with my loved ones.”

GLAD THAT I CAME, NOT SORRY TO DEPART

Published by Cassette for Timescapes, €25, in Dutch and Farsi, gladthaticame.bigcartel.com

Azam Masoumzadeh: Glad That I Came, Not Sorry to Depart

Read more about: Expo , Azam Masoumzadeh , Glad That I Came, Not Sorry to Depart , augmented reality , comics , Cassette for Timescapes