There is a strange kind of magic at work in wood engravings, in those elaborate and veined wood blocks that exist somewhere between appearance and disappearance. In the hands of painter and engraver Bruno Hellenbosch, that magic of matter becomes a game of hopscotch between old and modern, between Boccaccio's Decameron and Super Mario's Toad.

© Ivan Put

WHO IS BRUNO HELLENBOSCH?

Born in Brussels in 1977

Studies wood engraving at La Cambre, graduates in 2002

Ventures into painting and develops his exploration of wood engravings, seeking out the collision between old and modern

Together with Frédéric Penelle, sets up The Two Jimies in 2007, intervening in public space with large-scale combos of painting and wood engravings

The same year, he wins the prestigious Prix de la Gravure at the Centre de la Gravure et de l’Image Imprimée

In 2009, he wins the Prix de la COCOF at the Prix Médiatine

In 2018 he takes part in “XXL – Estampes monumentales contemporaines” at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Caen, for the first time hanging his matrices on the wall

In 2019, he collaborates with the American, Paris-based master printer Michael Woolworth on his imposing Decameron project

Shows his recent wood engravings and matrices at Galerie DYS

“The inertia that has settled over the world in the past year is familiar to me,” says Bruno Hellenbosch on an unusually sunny February morning in his loft in Molenbeek. The open space immediately reveals why. A small printing press and a table filled with chisels, gouges, knives, daubers, rollers and ink occupy one corner, while the rest of the open space is lined with dozens of one-metre-high inked matrices that lean against walls and cupboards. “I have always used the slowness that permeates working with wood. The slow pace allows me to think.”

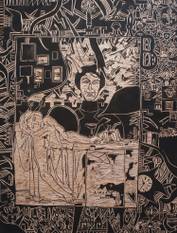

Wood engraving is digging into matter, mining sediments. A glorious paradox that stretches between removing and leaving appear, between processing that which you don’t want to show and leaving that which should appear on the paper untouched. Between the image that draws veins in the wood and its negative soaked in ink. Notched duration, congealed time. “Each small engraved zone represents five to six hours of work,” Bruno Hellenbosch explains. “Those wooden slabs accumulate moments of life. The viewer doesn’t experience those concrete moments, of course, but perhaps something of that accumulated duration permeates the labyrinthine veined wood.”

It is these matrices into which a life is sunk that Bruno Hellenbosch will show at Galerie DYS. “There will be a few prints, pieces that I made by hand, on cotton, to accentuate their uniqueness and to testify to the detachment I feel towards classical engraving. But I will mostly exhibit matrices, around twenty-five wooden boards that I rest on rafters against the wall, as here. Warehouse-style.” (Laughs)

© Ivan Put

“The first time I hung original wooden plates was when I exhibited at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Caen in 2018. I was struck by the appeal they had. Prints are nice, but I see them more as something to hand out to an audience, to make an event out of. There is something in the materiality of that wood that fascinates. For me too. Working with wood is very physical, very corporeal and sculptural. The ink gives it a kind of patina. I love how the ink finds its way into the grooves, adds texture and grain, makes things appear, surprises me. Wood offers resistance, more than a painting does, you engage in a kind of fight with matter.”

OLD-SCHOOL TINKERING

A fight with matter. It is a statement that applies not only to Bruno Hellenbosch’s permanently battered hands, but also to a content storm. In Caen, Bruno Hellenbosch put 100 metres of wood engravings on display at the exhibition “XXL – Estampes monumentales contemporaines”. One hundred matrices, divided into ten groups of ten, following the decimal structure of Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron. “Yeah, I felt like doing something very structured,” Bruno Hellenbosch laughs. “Away from the daily craziness of the studio, very focused. The form of The Decameron alone – ten characters each tell ten stories – gave me that structure and focus. That’s also what attracts me to the work of writers from OuLiPo (Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle, in which self-imposed restrictions, such as the absence of the letter ‘e’ in Perec’s La disparition, manage to generate boundless creativity, Ed.) such as Raymond Queneau and Georges Perec.”

Working with wood is very physical, very corporeal and sculptural. Wood offers resistance, you engage in a kind of fight with matter

In The Decameron, ten characters – three men and seven women – flee plague-stricken Florence. “I made the work between 2014 and 2018 so there is no link to the situation we are in today. But even with today’s eyes, the book goes beyond the pandemic, is essentially about the consequences of a crisis, whether economic, moral, religious or sanitary, as it is today. But also about the possibilities, the utopia after the crisis, about where happiness lies in life. It is a very modern book, a kind of laboratory that talks about sexual liberation, religious hypocrisy, powerful women... It is not without reason that (the controversial Italian film director who was horribly murdered, Ed.) Pier Paolo Pasolini undertook an adaptation in 1971, which is still the finest homage to the original. But The Decameron is also the invention of a new form of literature, the novella. That search for modernity in the old is what interests me above all.”

© Ivan Put

| Bruno Hellenbosch: “Each small engraved zone represents five to six hours of work. Those wooden slabs accumulate moments of life.”

It is striking how wood engraving continues to fascinate, to ignite a certain madness in artists. How the formal and narrative explorations of the medium by such great masters as Albrecht Dürer, Hokusai, MC Escher, Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward still appear fresh. “Wood engraving certainly carries that connotation of an old-school technique. But that is also what makes it so interesting to tinker with. After the First World War, the German expressionists appropriated the technique completely, turning it into something quite violent, urgent. I’m entirely in the spirit of reappropriation, of bringing a somewhat outdated technique into the present.”

FOOTPRINTS IN THE SAND

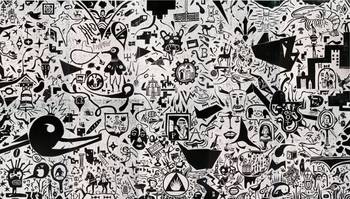

This juxtaposition produces a fascinating collision in Bruno Hellenbosch’s work. A kind of iconoclastic cloud of ambiguities and contradictions, in which a painting by the fifteenth-century Italian painter Piero della Francesca and the logo of Facebook float around. Where Chinese sculptures, Mayan fabrics, Greco-Roman motifs, African masks and Flemish primitives rub shoulders with Michael Jackson’s “Bad”, a vanitas of Picasso and traces of the Navajo. Where Memphis design, Fernand Léger’s workers, Malevitch’s black squares, a QR code and Toad, the mushroom from Super Mario Bros. experience a shared delirium.

It may be a polemical statement these days, when more and more people are striving for a kind of transcendental purity, but if you can’t appropriate things, you won’t get ahead as an artist. Art happens naturally through appropriation, you don’t create from nothing

“That corresponds to the images I digest daily,” laughs Bruno Hellenbosch. “I put my wooden plate here on the table, open the digital image library on my phone and start.” Captivated by one image, which, depending on the balance, ends up with several other images around it. “It’s not at all fixed in advance. I look for a certain balance in the assemblage, for reactions in what Deleuze & Guattari call the ‘agencement’. I draw with pencil or charcoal on the wood, then with Indian ink, and then cut into the wood. According to how the wood resists and exposes the image, things can disappear or appear.”

That spontaneous state of disappearing and appearing rhymes wonderfully with the mental space that the French philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman aims to erect in La ressemblance par contact: archéologie, anachronisme et modernité de l’empreinte. “His thinking about the value of the imprint, the print, has influenced me strongly,” says Bruno Hellenbosch. “He talks about a footprint in the sand and whether that footprint suggests absence or presence. Those sorts of ideas also occupy me when I carve in wood, think in negative, or decide to leave out the negative, the mirror writing, just to give the wood a life of its own.”

© Ivan Put

Bruno Hellenbosch also cites Élie Faure’s L’esprit des formes, part of the orange-clad volumes of Histoire de l’art that adorn his bookshelf. “That art history is, by the way, what Jean-Paul Belmondo reads in the bath in the opening scene of Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot le fou. In L’esprit des formes, for example, it is the way Faure compares a Gothic cathedral with the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco that fascinates me. How he himself builds a bridge across time and space.”

A BRILLIANT PARADOX

And then there is Aby Warburg’s image atlas Mnemosyne. The German art historian composed his history of art by gathering nearly 1,000 pictures from all sorts of sources on forty wooden panels. “Like Élie Faure, he crossed borders to create thematic ensembles. Kinship is more than proximity. This idea is very much in line with how I think in my work. The collision and juxtaposition of images from high and low culture, from different style periods, cultures and areas, gives a different kind of insight into the image, makes meanings slip. It is then not necessarily beauty that interests me in these images, but how they react to each other. It may be a polemical statement these days, when more and more people are striving for a kind of transcendental purity, demanding it, but if you can't appropriate things, you won’t get ahead as an artist. Art happens naturally through appropriation, you don’t create from nothing. I don’t see any problem in appropriating all those images. I don’t copy, I interpret, remix, digest.”

Wood engraving certainly carries that connotation of an old-school technique. But that is also what makes it so interesting to tinker with

Or not. In the corner where the printing press is located, Bruno Hellenbosch shows a series of wooden matrices that seem to have been torn from his hands before the last incision. Incomplete, unfinished, but also powerful and wonderfully fragile. “It is already beautiful. It shows the wood even more, that it is the matrix that interests me, that resists. Is that difficult? Psychologically, yes. (Grins) But it is a matter of accepting it. It is what it is.”

Refusing the end, accepting the unfinished... This is not a fait accompli, it is a conscious choice. Sometimes a difficult one, a choice that goes against the flow, but a choice nonetheless. A choice that makes room for the game, for the dialogue, for the clash, for the unruly relationship with the material, for the error, for the surprise, for the human hand, for life, that walks and falls and hurts and extinguishes.

© Ivan Put

| Bruno Hellenbosch’s studio in Molenbeek is lined with dozens of matrices: “I love how the wood offers resistance, how it surprises me, how the ink finds its way into the grooves, adds texture and grain.”

“That printing press belonged to Fred, by the way,” says Bruno Hellenbosch as he puts the matrices back against the wall. Fred Penelle was a benchmark in Bruno Hellenbosch’s life. “We studied engraving together at La Cambre, started to explore the medium together, and also tried to make it break out of tradition together. As ‘The Two Jimies’, we once created a thirty-metre wall during Nuit Blanche, on which we mixed cut wood engravings with painting and performance. After a while, Fred along with Yannick Jacquet focused on his ongoing installation project Mécaniques Discursives (an enchanting and poetic, absurd and exquisite mix of engraving and video projection, Ed.), and our artistic paths diverged somewhat. He passed away a year ago, around the time I started my residency at the MAAC (the Brussels laboratory for contemporary creation, Ed.) and the world was locked in by the pandemic. All this exploration of the medium and of ways of exhibiting, that I have undertaken in the last year, is a way of reconnecting with Fred, a way of honouring him.” A brilliant paradox stretches between removing and making appear.

BRUNO HELLENBOSCH: WOODCUTS

> 11/4, Galerie DYS, www.galeriedys.com

Bruno Hellenbosch: Woodcuts

Read more about: Expo , Bruno Hellenbosch , Galerie DYS , Woodcuts