“Molenbeek”, the first major solo exhibition of work by Philippe Vandenberg in Belgium since he took his own life in 2009, focuses on the late work that he made in the Brussels municipality. The exhibition shows him as a committed artist who saw his beloved Molenbeek as a platform for world problems.

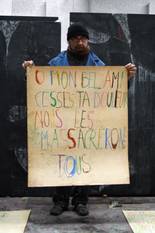

© Wouter Cox

| Philippe Vandenberg in his studio in Molenbeek

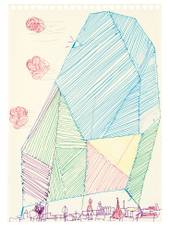

Philippe Vandenberg (1952-2009) had been a big name in the international art world for more than twenty-five years when he moved to Brussels from Ghent in 2006. The move was inevitably to be a pivotal moment in the oeuvre of the bilingual artist who studied literature, art history, and then painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ghent. His work, which eluded classifications of movement or genre, is now represented in various important collections around the world. Vandenberg not only made drawings and paintings but was also an author, and he was formally also very eclectic because his works were geometrical, figurative, abstract, and monochrome but he also used words. He used these styles as tools in his search for the human condition: the relationship between the human person and him/herself, the other, and society.

© Philippe Vandenberg Foundation

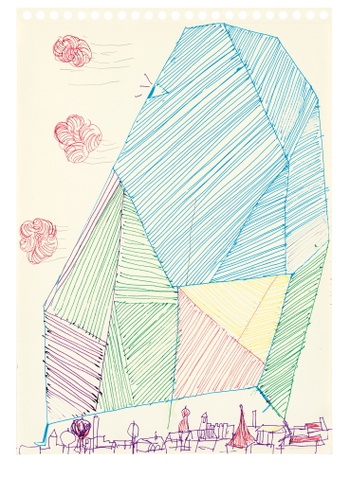

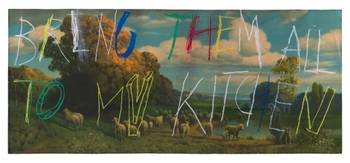

| Philippe Vandenberg, No Title, 2007

Another defining characteristic is undoubtedly his radicalness. Vandenberg sought contact with artistic audiences, but was utterly uncompromising. He did not get stuck in whatever turned out to be saleable. He also struggled with spiritual issues. His obsessive drawing and painting was a vain attempt to grasp reality, even for a moment. The death of his artistic companion and gallery holder Richard Foncke in 2005 and his move to Brussels following his children led to an even greater sense of isolation, which, along with his depression, contributed to his suicide. The three years that he worked in Molenbeek was therefore also the last, brief but also very productive and powerful period of his oeuvre.

FROM IEPERLAAN TO RIBAUCOURT

It is that period on which the exhibition at Bozar focuses, and more specifically on the drawings and paper sculptures that Vandenberg made in Molenbeek. The exhibition is organized in cooperation with the Philippe Vandenberg Foundation, which manages, promotes, and researches his work nationally and internationally, and of which his three children Hélène, Guillaume, and Mo are the driving forces.

To his daughter Hélène, this exhibition is important for several reasons. “First and foremost because it marks a return to Belgium, after a great attention for my father's work abroad. Since his death, we have primarily had international projects in cities like Hamburg, Paris, London, and Seoul. But despite his international orientation, my father is clearly a Belgian artist, and that makes the focus on Molenbeek especially interesting. In his last three years, he lived on Ieperlaan/boulevard d'Ypres and walked every day to his studio at Ribaucourt.”

© Philippe De Gobert

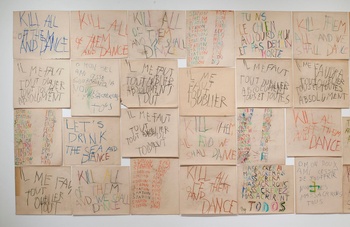

| Philippe Vandenberg often worked with slogans. There are inner mantras (“Il me faut tout oublier”) as well as vindictive statements (“Kill them all”)

The choice of the Molenbeek drawings was made by Barry Rosen, the curator from New York who has previously worked with other foundations of radical artists, such as those of Eva Hesse, Lee Lozano, or Dieter Roth. Hélène Vandenberghe: “He discovered my father's work at Hauser and Wirth in London, and later developed a friendship with him. He decided on the last three years in Molenbeek because that work is so contemporary. It focuses on an element that has often been neglected due to a different interpretation of his work that is especially dominant in Belgium. Internationally, there is more interest in his political engagement, and the story of the tormented artist, the depression, and the suicide is not so prominent there. There is a lot of lucidity and humour in these works. My father had great hopes for humanity.”

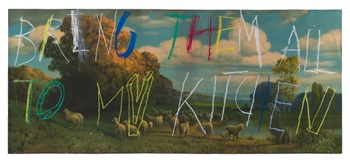

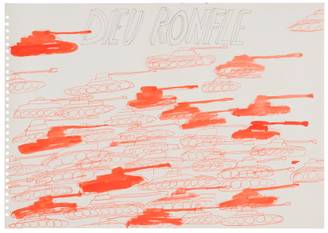

ST. JOHN’S MILLBROOK

What is particularly striking as you walk through the exhibition is the almost childlike, candid multicolouredness that has been applied with pastels and even markers to the recycled sheets of paper and carboard, plywood, and other found objects that Vandenberg used as his matrix. To draw, but especially to make compositions of letters, words, and slogans in sharp and loud handwriting. “By working on found objects, Vandenberg literally brings the city into his work,” says the researcher Johannes Muselaers from the foundation. “He would go out looking for these objects with a little cart. He would paint over discarded paintings or recycle the boxes in which his painting materials were delivered, to paint slogans on them like 'Un grand amour suffit' or 'Un homme ça dit rien, ça peint'. Such a 'boîte de colère' might also be seen as a metaphor for his studio, which became almost too small for all the feelings that he brought in there himself or that forced their way in via the media.”

© Jean-Pierre Stoop

| In Molenbeek, Philippe Vandenberg struggled with increasing feelings of isolation and depression, which culminated in suicide in 2009

Due to the limited number of figurative works, the exhibition appears relatively conceptual. But the recycled materials also put the sacrality of the art world into perspective, and the colours seek to make direct contact with the viewer. In contrast to the often alarming messages, the colours also hint at Vandenberg's occasionally satirical approach.

Another leitmotif is the blending of the personal and the local with the political and the public dimensions of current affairs and world history. This is evident schematically in the mosaic of the large sheets of drawing paper that are covered in slogans in the first room of the exhibition.

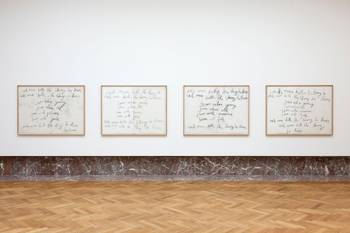

Muselaers: “You can see two voices here. On the one hand, there are inner mantras in French, like 'Il me faut tout oublier', through which he controlled his feelings in the safety of his studio, and on the other hand there are threatening statements in English such as 'Kill them all', which are reminiscent of slogans at protest marches. Incidentally, he picked up the slogan 'Kill the Dog' during the fundamentalist protests against Salman Rushdie's novel The Satanic Verses. Vandenberg thus associates himself with the critical artist who is at the forefront of social debate and is therefore besieged by the masses.” The same image recurs in one of the rooms at the back, where mumbled prayers like “Prions pour la madonna de Molenbeek” alternate with “We'll kick your ass out of St. John's Millbrook”. “As though a crowd of people stood banging at the door of his studio.”

Despite his international orientation, my father is clearly a Belgian artist. That makes the focus on Molenbeek especially interesting

St. John's Millbrook – the reference will certainly not escape you. “He had a great love for Molenbeek and it is very prominent in his work,” Hélène Vandenberghe says. “He spent hours walking around Molenbeek with his sketchpad and he talked to a lot of people. He was intrigued by the tension that lay just under the surface. Between high and low, between the colourful and the grey, between rich and poor, progressive and conservative, moderate and radical.”

In The Molenbeek Drawings, a series of seventy-seven sheets, he simplifies the impressions of his daily walks in the microcosm between his home and his studio almost into icons of an occasionally very raw social reality.

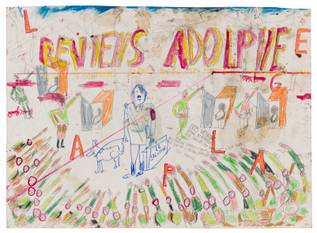

HITLERS AND SWASTIKAS

The cycle brought together at the exhibition under the heading “Art and Resistance” likewise combines social-critical and autobiographical elements. This time, the matrices of the drawings are desk mats on which Vandenberg's old doodles, telephone numbers, names, and notes can still be seen. The work of James Ensor comes to mind when you see the small human figures that are drawn here and which together form an agitated crowd. Above them we see the towering figure of Hitler, carrying a briefcase marked “La solution”. “Reviens Adolphe, on t'aime,” the masses cry.

© Philippe Vandenberg Foundation

| Philippe Vandenberg, No Title, 2008

Along with the swastika, Hitler is a recurring theme in Vandenberg's work. “These are the most famous symbols of evil and dictatorship,” his daughter explains. “He does not aim to shock, but to provoke. Provocation is a way for the artist to make contact with the outside world. But my father did not want to make compromises or eschew taboos. The dictator is also a symbol of censorship and the fact that the individual, nuance, individual freedom, and thus art is drowned out by the slogans of the masses. World leaders were already presenting themselves as more and more dictatorial. My father took all these conclusions and withdrew to his studio as a 'witness for the prosecution.' To hold a mirror up to society. But also to make his pamphlets against radicalization, unity of thought, and dictatorships. That is why the exhibition is so relevant now. Father was a seismograph who would not have been surprised by what is happening today on the Greek islands, the United States, or Belarus.”

My father withdrew to his studio as a “witness for the prosecution.” To hold a mirror up to society. But also to make his pamphlets against radicalization, unity of thought, and dictatorships

In Witness for the Prosecution, the documentary film by Hans Theys that is being shown at the exhibition, you see the artist in his studio, and Vandenberg does indeed discuss his Hitler drawings in connection with Putin and China. “I think we must be alert,” he adds. “To preserve life.”

The question that this ambiguous work continues to ask after we leave the exhibition is indeed whether or not we are sufficiently alert. And whether the loneliness and doubt that ultimately became too much for Vandenberg at the end were the result of his radical artistry or of the limited extent to which the artist's sensitivities were shared by society more broadly.

PHILIPPE VANDENBERG: MOLENBEEK

> 3/1, Bozar, www.bozar.be

Philippe Vandenberg: Molenbeek

Read more about: Expo , Molenbeek , Philippe Vandenberg , Philippe Vandenberg Foundation , Bozar

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.