David Hockney is arguably one of the most influential and beloved image makers of our day. At the same time, the 84-year-old Briton escapes any categorisation. With a double bill, Bozar dives into both the rich past and bold present of the charming and flamboyant colourist who playfully navigates between his Landrover, his easel and his iPad. A David Hockney alphabet, because...well, why not?

David Hockney, from A to Z

© Jonathan Wilkinson

| David Hockney in his Normandy studio, 24 February 2021

A Bigger picture.

Looking at the more than half a million visitors swarming “A Bigger Picture”, David Hockney's 2012 show at the London Royal Academy, it must have been a no-brainer for Bozar to honour one of the most successful living artists of our day with not one but two exhibitions. Next to a grand retrospective featuring his “Works from the Tate Collection, 1954-2017”, curated by Helen Little, formerly curator at Tate Britain and currently at Leeds Art Gallery, Bozar's double bill is also presenting “The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020”, a seductive selection of the iPad paintings Hockney made around the time of the first lockdown. That last show is curated by Edith Devaney, responsible for the success of Hockney's 2012 art blockbuster and currently Managing Director and Curator for the master himself.

Bestseller.

Hockney's popularity isn't limited to visitor numbers. In 2018, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) was sold at auction by Christie's in New York. With a whopping 90.3 million dollars the painting from 1972 set the auction record for a living artist. Jeff Koons, whose Balloon Dog (Orange) thus was knocked of the throne, took his revenge a year later by managing to sell his Rabbit for 91 million dollars. Hockney won't lose any sleep over it, says Edith Devaney: “For David, it's all about the image making.”

Colourist extraordinaire.

“I asked somebody once, 'What colour is the road?' He looked at it briefly and said 'It's not just grey, is it?' I said, 'No it's not, if you really look.' But you have to really look.” That is what David Hockney said in connection with the 2019 exhibition “Hockney – Van Gogh: The Joy of Nature” at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, where the two superior colourists entered into dialogue. His lush use of colour, which really comes to the fore in his California paintings from the 1960s, when he started using acrylic paint, is undoubtedly one of the main reasons for his magnetic appeal. It finds an eager interlocutor in the eternal cycles of nature, which lured him from seasonless Los Angeles back to Europe at the turn of the millennium.

© David Hockney

| David Hockney’s ‘My Parents’ (1977): “Never worry about what the neighbours think,” was the powerful motto they lived by.

Do your own thing.

Long before David Hockney was mentioned alongside Van Gogh and the likes, his extraordinary artistic career was by no means certain, Helen Little explains. “Hockney was born in Bradford, a big industrial city in the north of England, in 1937, as the fourth of five children in a working-class family.” Certainly not the ideal background for someone aspiring to becoming an artist, were it not for the family motto. “'Never worry about what the neighbours think. We should all be ourselves and get on with our lives in our way.' That was a very powerful message that David lived by when fighting to become an artist and taking the very traditional, highly figurative, observational art training he received at Bradford School of Art to try and create a space for himself at the Royal College of Art in 1959, where he, a working-class boy from the North of England struggling with his sexuality and his identity, was considered an outsider. It is that motto that early on made him decide that he was not going to become the kind of artist fashionable at the time – when American abstract paintings were in vogue – but that he was going to do things his own way: make figurative pictures, pictures that speak to himself, his story, his struggles and his life. That all contributed to his becoming such a rising star on the London art scene at the time and really set out this bold path that he has been carrying on throughout his 60 years of being an artist.”

Experimentation.

His highly personal artistic path led to a preference for experimentation at the crossroads with his eternal ambition to look intensely at the world around him. Photography became a lifelong companion, first as a touchstone for his naturalistic American canvases, later as a way of posing a problem, but Hockney is also busy with etchings, prints, Xerox machines, faxes and iPads. “It's the constant throughout his studio life,” says Helen Little. “The different mediums help him express certain encounters in different ways.” “It's amazing how he keeps picking up new mediums and works tirelessly, like a student, uncompromising in his determination to master the medium,” agrees Edith Devaney.

Family & friends.

In 1957, Hockney, then only 20 years old, exhibits and sells Portrait of My Father at the “Yorkshire Artists Exhibition” in Leeds Art Gallery. It is the first example of a whole series of portraits and double portraits that he will be drawing from his intimate relationships. His parents, love interests, friends and even his dogs figure in often emotionally highly charged canvases that give an insight into his personal life. “Hockney's work is very diaristic,” says Helen Little. “It is very revealing of a very interesting and exciting personal world, of the people that have come in and out of his life. Very often, Hockney is trying to work those relationships out himself, always encouraging the viewer to take his place in the dynamic of the relationship.”

It’s amazing how David Hockney keeps picking up new mediums and works tirelessly, like a student, uncompromising in his determination to master the medium

Great expectations.

“Like many British artists of the early 1960s, David Hockney followed the lure of America,” Helen Little says. “But his first visit to New York in 1961, though full of promise, was a bit of an anticlimax. He found a city that was in the midst of dreadful social upheaval, a great racial divide, poor health care and so on. Upon returning from his visit to the States he makes The Rake's Progress, a series of sixteen etchings in which he compares 1960s New York to painter William Hogarth's 18th century London. It's a grimmer, darker story than he was expecting. But when he travels to California in 1964, it seems that he finds the paradise, this hedonic lifestyle and culture of America that he was hoping for. It's where he discovers a much freer, more tolerant, more glamorous society, with a much livelier gay scene, and where his very celebrated and iconic pictures of men in showers, boys in swimming pools and beautiful architecture are made.”

Human vs cyclops.

“It's a mistake when people see David as someone who is a real technophile,” says Edith Devaney. “He is not. He has a clear interest in new technologies and great technical ability, but he only sees technology as possibilities in the image making process. As a means rather than an end.” In particular, Hockney's long relationship with the camera and the lens clearly shows that, Helen Little adds. “His ventures into Polaroid photography in the 1960s have led to his classic LA paintings. But in fact, they're a reminder of a direction that he really didn't want to take. He didn't want to make paintings that looked like photographs, he wanted them in a much more tangible way to reflect the manner in which our eye and our brain move around a subject and have many different points of reference and perspective.” “He has always pushed very hard against the cyclopean view of the world,” confirms Edith Devaney. “'Your eye is so much more sophisticated than the camera lens,' he thinks.”

© David Hockney

| ‘Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy’ (1970-1971): “Hockney’s work is very diaristic.”

iPad.

With “The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020”, Bozar is also showing David Hockney's most recent technological adventure: a series of 116 iPad paintings made during the first lockdown. “When David sent those paintings to his close friends, it changed our perceptions of the situation we were in, this utter sense of despair and anxiety,” Edith Devaney testifies. “'They can't cancel spring,' he wrote.” It is a beautiful paradox, where Hockney uses the very same technology that inexorably demands our attention to return our gaze to nature. “To David it is the only way to register how the landscape responds to the changing of the seasons. 'You can't do it in paint, because you wouldn't be quick enough.' It is about that transience of light, that moment when you see the morning mist. The iPad allows him to get down the essence of those fleeting moments in twenty minutes. It's remarkable how he applies his experience of over 60 years to that new medium. How he works on that tiny screen, knowing the size he is going to print the pictures and how each gesture is going to be magnified. How he works through different layers in his Brushes app, especially adapted for him, sliding them out and pushing them back in.” Spring will carry on, David Hockney will carry on.

Joy.

Despite his sense of experimentation, David Hockney does not forget his roots. On the contrary, his humble origins form the standard by which he measures his artistic practice. Art is a question of wonder, of the joy of looking intensely and of telling enchanting stories and it should tell those stories in a generous way, in a language understandable by everyone and in particular by his mother. “Those sort of family values have in a very meaningful way shaped Hockney's views,” says Helen Little. “He once said that he has the vanity of an artist, meaning that he wants his work to be seen. He genuinely delights in people taking joy in seeing his work.”

Knowledge.

David Hockney is a brilliant mind, both Edith Devaney and Helen Little assert. A man who is eager in life and has an insatiable hunger for knowledge. With Secret Knowledge, he also has a book to his name that argues that European painters were observing the world with optical tools long before the invention of photography. A thesis with repercussions for the relationship between reality and art, which echo in his own complex relationship with photography.

© David Hockney

| David Hockney’s iPad painting “No. 147” (5 April 2020): “They can’t cancel spring.”

Landscape painter.

An easel in the countryside appears completely out of date, but David Hockney could care less. The artist defiantly keeps on painting in the open outdoors. “In the 1960s or 1970s, it would have been hard to predict that David would have moved into that direction,” Edith Devaney says. But that is Hockney. “He never leaves anything behind. He could start doing portraits again tomorrow and it wouldn't be surprising. In fact, he's done a few still lifes recently, which are extraordinary.”

Moving focus.

“When in 1983, David Hockney started studying Chinese scrolls – one of many examples of his tireless efforts to try to dispel the myth that Western art history is a superior form of depicting the world – his immediate response to the many perspectives integrated in this one body of work, comes in a series of lithographic prints, called Moving Focus,” Helen Little says. “It is a title that is also telling of his own philosophy: that we're never standing still, that the world is constantly moving around us, and that we are constantly moving in relation to it.” It is an idea that he also develops in his explorations of photography, whether driving through the landscape in a Jeep with nine cameras, to be able to look at it from different angles, or creating photo collages in which he stitches thousands of images together to create a composite image with multiple perspectives and realities. As he says himself: “The eye is always moving; if it isn't moving you are dead.”

Nature.

“He is not some crazy outdoorsy person,” Edith Devaney says, when speaking about Hockney's iPad excursions into the countryside. “He doesn't get deep into ecology or the science of plant life, and I know he has always enjoyed city life. It's all about seeking out the beauty of the world. Nature's appeal is very much a visual one, it is an infinite source of subject matter.”

Right from the get-go, he fought against his characterization as a pop artist. He did not want to belong to any particular artistic movement, he wanted to create his own path

Order of merit.

In 2012, David Hockney was appointed a member of the Order of Merit by the Queen. Twelve years earlier, he had refused a knighthood because: “I don't value prizes of any sort. I value my friends.”

Pop artist for a minute.

Although life during the swinging sixties brought David Hockney into the path of pop art icon Andy Warhol, and the latter even did some portraits of the Briton, “right from the get-go, he fought against his characterization as a pop artist,” says Helen Little. “He did not want to belong to any particular artistic movement, he wanted to create his own path. His Tea Painting is the closest Hockney ever came to pop art, he once said, and I think that's solely by virtue of the fact that he used a brand of tea (Typhoo) that just happened to be lying around the studio.” The Tea Painting was one of the works that was shown at “Young Contemporaries” a show at the Royal College of Art in 1962, that launched the British pop artists.

Queen's Window.

Since 2018, Westminster Abbey has its own Hockney. The stained-glass window, commissioned to celebrate the reign of Queen Elizabeth II, depicts a country scene featuring hawthorn blossom growing near Bradford and was designed on the iPad.

Representation.

David Hockney's eternal quest: How to capture the complexity of the three dimensions of the world in the two dimensions of the plane?

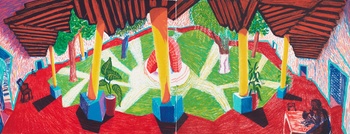

© David Hockney

| ‘Hotel Acatlan: Two Weeks Later’ (1985): bend it like Hockney.

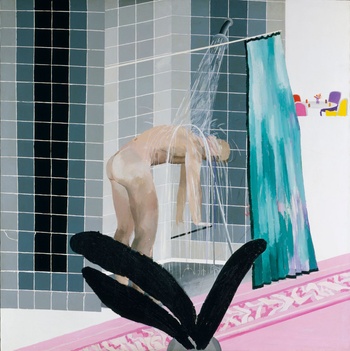

Sexuality.

One of the reasons why David Hockney so quickly rose to fame, against all the odds, had to do with an intimate part of himself. “I think we as a contemporary audience take for granted how radical and how brave his early work really was,” Helen Little clarifies. “These days, queer histories are only really just being opened up and explored historically. At the time when Hockney started producing work, and in a very coded, secret yet raw way was telling the story of his own struggles, homosexuality was still illegal in the UK.” Although the artist's work in the 1960s would be filled with showering men and boys by the pool, his mother only grasped that he was homosexual when he was 45. In a beautiful, touching letter, she, who had always supported her son's artistic aspirations, asked him to forgive her for not being there when he had most needed her.

Tate.

“Generosity is a word I use a lot when talking about David Hockney,” Helen Little says. “Not in the least because of the lifelong relationship that he has maintained with Tate: as a young artist gravitating to Tate in order to enjoy encounters with living artists and seeing works by historical figures that he loved, and, later in his career, giving extraordinary gifts to the institution to guarantee the audience to see his works in public collections.”

Underground.

Hockney's popularity owes a lot to the recognisability of his work and the freshness of its seemingly naive language. Though at times, that naivety fails to appeal. When his new design for London's Piccadilly Circus underground station was presented a couple of months ago, it was met with some resistance, to say the least. The artwork, a hilarious take on the Tube logo, including an “s” inserted at the last moment, sparked reactions like: “Hey, David Hockney, a four-year-old called – he wants his subway art back.”

Hockney once said that he has the vanity of an artist, meaning that he wants his work to be seen. He genuinely delights in people taking joy in seeing his work

Vanity.

David Hockney not only created portraits of his loved ones, he also made countless self-portraits. Apart from those mirror images, you can also consult the likes of Andy Warhol and Lucian Freud for a different take on the British icon.

Westwood, Vivienne.

The legend goes that David Hockney dyed his hair blond after seeing a television ad for Clairol hair dye in the 1960s, at a time when he had visited the United States for the first time and was trying to craft his identity as an artist and a public figure. The fact is that not only his canvases are explosions of vibrant colours but that with his dandy aesthetic, stylish suits and quirky colour combinations, the artist is an inspiration to fashion designers himself. Christopher Bailey, once the creative director of Burberry, is said to have based entire collections on Hockney's style, and fashion superstar Vivienne Westwood named a checked jacket after him.

Xerox.

In 1986, David Hockney produced a series of Home Made Prints, using a friend's office copy machine, quickly discovering that it could just as well function as a printing machine. “In fact, this is the closest I've ever come in printing to what it's like to paint: I can put something down, evaluate it, alter it, revise it, all in a matter of seconds.”

© David Hockney

| ‘Man in Shower in Beverly Hills’ (1964): “As a contemporary audience we take for granted how radical and how brave his early work really was, at a time when homosexuality was still illegal.”

Yorkshire Wolds.

When his mother died at the age of 98 in 1999, Hockney took some distance from painting. He returned from California to go and live in the Yorkshire countryside where she had passed away. It is there that he drove around with his Land Rover, on which nine high-definition cameras were mounted to record the Yorkshire Wolds in all four seasons.

Zauberflöte.

David Hockney's 35 backdrops for a production of Mozart's The Magic Flute at the Glyndebourne Festival Opera in 1977-1978 are part of a series of stage designs, which began with the theatre design for a revival of Ubu Roi at London's Royal Court Theatre in 1966. “It was just another outlet for Hockney's desire to work in as many different mediums,” says Helen Little. “It was a way to challenge himself technically. He has always, since childhood, enjoyed live music, going to concert halls, theatre, and especially opera.”

DAVID HOCKNEY: WORKS FROM THE TATE COLLECTION, 1954-2017 & THE ARRIVAL OF SPRING, NORMANDY, 2020

8/10 > 23/1, Bozar, www.bozar.be

Read more about: Expo , david hockney , Bozar