With “Garden Room” Anne Daems returns to the place where 22 years ago she won the Young Belgian Painters Award, now the Belgian Art Prize. Her first solo exhibition at Bozar is a small but precious experience that gets under your skin.

© Heleen Rodiers

Also read: Brussels middenveld lanceert petitie tegen uitblijven regering: ‘Balanceren op het randje’

WHO IS ANNE DAEMS?

• Born in 1966 in Lier, grows up in Berlaar

• Studies photography at Sint- Lukas Brussels, explores film and video during an extra year, and starts drawing too during a two-year residence at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam

• In 1999, wins the Young Belgian Painters Award, currently the Belgian Art Prize

• Exhibits her photographs, drawings, videos and installations at De Pont in Tilburg, The Drawing Center in New York, the Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, and Witte de With in Rotterdam, and is represented by the renowned Antwerp gallery Micheline Szwajcer

• “Garden Room” is her first solo exhibition at Bozar

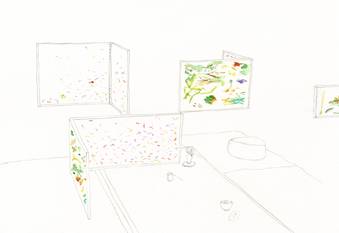

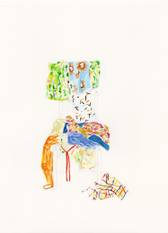

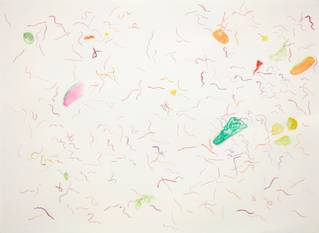

There is a wonderful intimacy in the Council Room at Bozar. An inaudible rustling reveals itself as the slightest stirring of a mystery. In subtle and nimble drawings and watercolours, in clay sculptures and on folding screens, you discover the protagonists in a tiny spectacle. Worms, slugs, flowers and leftover green waste swarm over the paper sheets, on the clay objects in the “Garden Room” that Anne Daems has installed there. A piece of domesticated nature shows itself as a sparse poem, which slowly creeps to an open, inevitable end. Already containing a new beginning.

There is a grandiose magnificence in those small movements, congealed to a standstill. In this silent and fragile poetry, this everyday storm that seems to be silent to human ears, but here bulges with meaning and colour.

My city garden is the place where nettles and herbs grow, where the flowers I paint while listening to podcasts about murder mysteries stand, where I remove slugs, where worms process compost. At the same time, this can be anyone’s garden

Under Horta's high sky, Anne Daems' “Garden Room” draws you to the low ground. To a kind of unfathomable simplicity. Between the non-functional small screens and tables far too low you complete a ritual on your knees, a ceremony. “I grew up with an artist as a father,” says Anne Daems. “Art was always there, very natural, something I felt a kinship with. Similarly, Japan was a part of my upbringing. My father spent a lot of time there, first for macrobiotics – not always easy (laughs) – and Okido yoga, then for calligraphy. And then came the tea. He has been a tea master for perhaps twenty years now. The folding screens are based on the wind walls used in tea ceremonies. There you sit on the floor, too, on a tatami mat.”

HORTA'S BACK DOOR

That spatial intervention was not the only one. “The first time I saw the Council Room empty, I immediately felt that something was not right,” says Anne Daems. “On the back wall, it turned out that the skirting didn't continue because it's a false wall. Hidden behind them are Victor Horta's original doors, the same ones through which you enter the room. So I decided to restore the balance and draw them on the wall.”

© Heleen Rodiers

| Anne Daems in her “Garden Room” at Bozar.

It seems like a detail, but by bringing the reflection of the doors back in, the space transforms, opens up to an intimacy. Like a back door to Anne Daems' garden. “My city garden is not that big, but it's very diverse. It's the place where nettles and herbs grow, where the flowers I paint while listening to podcasts about murder mysteries stand (laughs), where I remove slugs, where worms churn the earth and process compost. At the same time, it can be anyone's garden.”

“How you organise your garden reveals how you think about many things,” Anne Daems says. Transience is part of her gaze. “That's why I made the clay sculptures too, after the bowls on the kitchen counter in which things gather at the end of the day. I left them unfired because that gives them a beautiful fragility. And when they break down, I can throw them back on the compost pile.”

CARAMEL FUDGE

Anne Daems' gaze nestles between the everyday and the eternal, between blossoming and transience − two doors to the same space. She learned to look at things by studying photography at Sint-Lukas Brussels. “But that quickly became too technical, so I lost interest a bit and eventually ended up at the film and video department. In drawing too, it's not the technicality, the fact that something is drawn correctly, that makes a good drawing for me. Sometimes a 'bad' drawing can be better, radiate more energy, demand more attention.”

Anything can be fascinating or exciting to look at. There is a lot of drama in an old woman at her kitchen table peeling a cabbage, as the film director Frederick Wiseman once said

“When you take pictures, you go out into the world. When you draw, you sit at home alone and it's all about the things you think,” says Anne Daems. “Though that too flows from looking, experiencing.” From that moment when the eye lingers on the spectacularly unspectacular. “Anything can be fascinating or exciting to look at. There is a lot of drama in an old woman at her kitchen table peeling a cabbage, as the film director Frederick Wiseman once said.”

Anne Daems extracts a fragile, multi-layered beauty from this banality with palpable devotion. In her “Garden Room”, time slows down and solidifies, is purged into a charged space. “Sometimes you can say a lot with very little. I recently heard short story writer Lydia Davis say during a lecture that in order to write well, you have to go very deep into things, try to make sense of them, accumulate experiences in life, analyze, think and see a lot. Once you've done that, there's nothing stopping you from writing about caramel fudge.” (Laughs)

That is the sweet anecdote that unfolds into inalienable truth, the worm that digs wormholes into endings and new beginnings, the cabbage that is stripped of its bracts at a kitchen table and ends up as a tiny spectacle, a magnificent moment.

ANNE DAEMS: GARDEN ROOM

> 31/10, Bozar, www.bozar.be

Anne Daems: Garden Room

Read more about: Expo , Anne Daems , Bozar , Under the skin