There was a time when the name Víkingur Ólafsson only rang a bell with the biggest aficionados of classical music. But that time has passed. After four albums on the renowned Deutsche Grammophon label, the Icelandic pianist (37) is on the verge of breaking out of the classical bubble and becoming a global phenomenon.

Víkingur Ólafsson: “Debussy said that an artist’s obligation is to escape his own success. It is one of my favorite quotes.”

Víkingur Ólafsson

- Icelandic pianist, born in 1984, who grew up in Reykjavik as the son of a piano teacher

- Studied at the famous Juilliard School in New York

- Has played with orchestras such as the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the Göteborg Symphony Orchestra and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra

- Has released several albums interpreting works by composers as diverse as Bach, Philip Glass, Debussy and Mozart in his own unique way

When Víkingur Ólafsson sits down for the interview, almost nothing gives away that I'm sitting in front of one of classical music's biggest stars. Almost. We're sitting at the offices of record label mastodon Universal, not quite the place a classical music journalist visits daily. When I start my recording, I get a friendly but stern nudge: “Forty minutes.” Ólafsson came straight from a photoshoot, still has to head to both Klara and Musiq3, all the Belgian venues on his tour want to record promotional video's ... The classical musician really gets the popstar treatment. Be it a popstar that plays Bach, Debussy or Mozart.

“That's the advantage though, that I'm not a popstar. I am playing someone else's music, so I don't have to talk about myself all the time. I have these wonderful co-creators in Johann Sebastian and Wolfie. It's very freeing, I wouldn't only like to talk about my little world.”

You consciously call them co-creators?

Víkingur Ólafsson: You have to criticize the music you play. Deeply understand it from a compositional perspective, see it from the composer's eye. I think if Bach were alive today, he would never play the Goldberg Variations the same way twice. I'm absolutely sure he would do different tempi, Mozart the same. Have you ever tried writing out music and deciding where the crescendo and the decrescendo are? Where does the phrase start? Where is the staccato? Is it allegro vivace or allegro con brio? When you try that it feels horribly limiting.

So it seems crazy to me to pretend that a Mozart score can reveal everything you have to know about how the music should sound. That music was written out for an audience of 200 drunk aristocrats in Vienna. That's a different thing than playing it at the BBC Proms for almost 6,000 people. That's why I think we have to be open-minded about it. Nobody is pretending we need the same costumes for King Lear as the ones they wore in The Globe 400 years ago. That's a ridiculous idea. I think classical music should be redefined from generation to generation and performer to performer, just like we would with the works of Shakespeare.

Your latest album, the one you will be showcasing at Flagey, is all about Mozart and his contemporaries. How do you wish to redefine him?

Ólafsson: I'm focusing specifically on his dark side. Mozart is mainly known for his playful and inventive compositions in a major key. The minor pieces are really an exception. But the older he got, the darker the music. And when Wolfie goes into minor, he means business! All that melancholic, 19th century, romantic repertoire is unthinkable without him. He was really ahead of his time.

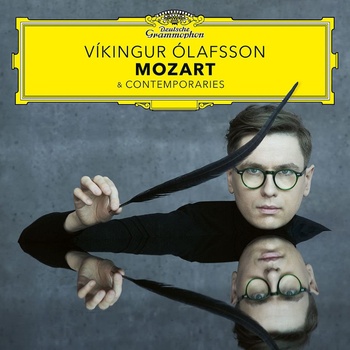

You could say he was the first indie musician, in the sense that he broke away from aristocracy and started his own concert series. He hired an orchestra, he sold tickets, he hung posters … He did everything. The last ten years of his life were one big quest for independence and freedom from tradition. I want to try and reflect that aspect of Mozart. That's also why I opted for the image with the black feather on the cover. It's dark, but not heavy. The music has this featherlight balance between tragedy and beauty. It's on top of the Deutsche Grammophon logo, which has never happened before and will never happen again. Another nod to the way Mozart took tradition and twisted it.

The album cover is indeed striking. In fact, all your albums come with a specific visual identity. Do you feel that's an important part of your work as an artist?

Ólafsson: I do keep full creative control over an album. People often criticise branding in classical music, but I don't see it as something superficial. With many big labels, when they take over the marketing you are allowing yourself to be sculpted into something you're not. The industry wants to see you defined by your past successes and they want to build on that. Because its proven and they want to form you into a brand that anyone can identify to. As an artist, you have to be one step ahead of that. Govern who you are and let the branding spring from that.

So a day like today, filled to the brim with interviews and promotional obligations, I don't see it as something external to the music. I see it as another way of expressing myself. It's not just me trying to sell an album. It's having a conversation about Mozart and Bach and Debussy, about the art of performing or recording, and I admit I quite enjoy these conversations.

'The older Mozart got, the darker the music. And when Wolfie goes into minor, he means business!'

Is that creative control also how you managed to release four immensely diverse records? You went from Philip Glass to Bach, then Debussy and now Mozart. Not exactly a stereotypical repertoire for a classical musician.

Ólafsson: I think it's just how I am. I like diverse styles of music. But it wasn't always easy to go this way. When I did my first album for Deutsche Grammophon, the Philip Glass album, so many people labelled me as a minimalist pianist. There were loud voices also from within the label that told me my second album must be American. I immediately resisted that, rather forcefully. I even threatened to leave, because my heart was set on doing a Bach album. I knew that if I were to do another Glass album it would announce to the world that I'm someone I'm not. That this is all I do. Luckily the second one, centred around Bach, turned out to be an even bigger success. But once that happened, they told me that my third album had to be Bach.

It goes back to one of my favourite quotes by Claude Debussy. He said that an artist's obligation is to escape his own success. You can't write another Claire de lune, you have to go on and write La mer. You can't write a second Fifth Symphony; you have to go on and write a Sixth. You can only write one Moonlight Sonata. When everyone wants you to become this one thing, you have to resist it and know for yourself where you want to go. Now that I've made it this far, I think it's a fun game to have people guessing what my next album is going to be. (Laughs)

Read more about: Muziek , Víkingur Ólafsson , Mozart , deutsche grammophon , Bozar