In "Sophie Podolski: Le pays où tout est permis", Wiels is bringing a poet-artist of mythic proportions and her forgotten oeuvre back into the limelight. We explore the "Country Where Everything Is Permitted" with curator Caroline Dumalin, American writer Chris Kraus, and Brussels filmmaker and kindred spirit Joëlle de La Casinière.

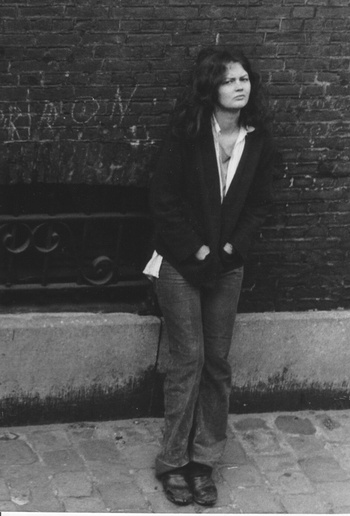

Sophie Podolski & Joëlle de La Casinière.

It is 1969, spring in Brussels. There is a knock at the door of rue de l’Aurore 25. “Hi, I’m Sophie. I’m sixteen.” “Mischievous. She was incredibly mischievous,” Joëlle de La Casinière laughs with much warmth about the way Sophie Podolski walked into her life, and the house where she and four other artists shared studios and living space. “Apart from an unmistakeable air of tragedy, she also had an incredible sense of humour and an intelligence and sophistication that you rarely see in someone so young. We all fell in love with her on the spot.”

The Brussels-based filmmaker took the initiative for the exhibition that Wiels is devoting to the work of Sophie Podolski, an artist who wrote and drew a radical, unsettling, and dizzying oeuvre between 1967 and 1974, and who at the end of this short but intense period, took her own life at only 21 years old. The raw materials for this first exhibition ever dedicated to her come from archive files that Joëlle de La Casinière carefully kept for more than forty years after Sophie Podolski’s death, and which, after seeing Wiels’s tenth anniversary exhibition “The Absent Museum”, she presented as evidence of another “absent artist”.

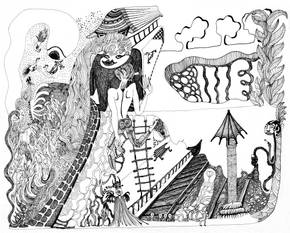

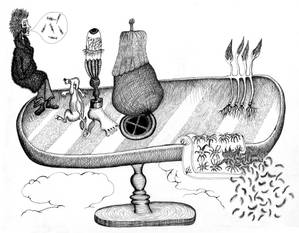

“The first impulse you might have would be to romanticize Sophie Podolski,” Caroline Dumalin, curator of “Sophie Podolski: Le pays où tout est permis”, tells us. “She was a very young artistic talent who arrived bang in the middle of a turbulent period of social and cultural revolutions and anti-authoritarian, anti-conformist attitudes. She eagerly entered this adult world of second-wave feminism, sexual liberation, anti-psychiatry, the questioning and abolition of traditional worldviews and conventional relationships between men and women, medical diagnostics and normality, etc. And she confronted it with a very compelling, expressive, almost visionary language. It is coloured by associations that are bizarre and fantastical, and without ever mincing her words."

Sophie Podolski.

"It was taboo-shattering work that contained enormous musicality and graphic sensitivity. And then there’s the tragedy of her illness, schizophrenia, which shows through in her work and which drove her painful and premature death. All this, and the fact that her work was hidden for more than 40 years, makes her an immensely attractive figure.”

“As well as being really blown away and inspired by Podolski’s work, I am very moved by the effort of preservation and the loyalty of Joëlle de La Casinière to their friendship, to the work, and to that time in their lives,” confirms American writer Chris Kraus, who was asked by Wiels to write a contribution for the exhibition catalogue.

“I was only aware of her thanks to the five or six references that Roberto Bolaño [one of the most significant Latin American literary voices of his generation – KS] made to her in several of his books. And when I read them, I didn’t even know if she was real. My initial reaction to her texts and her graphic art was shock, because there was so much of it. This wasn’t just a little blip on the screen. She was incredibly prolific for a very short but very intense period of time. And her graphic poems look like they could have been drawn yesterday, there is nothing particularly dated about them at all.”

Sophie Podolski (on the left) and Joëlle de La Casinière

This must be the place

“It’s funny, even though we’re close in age, we’re not close in culture,” Chris Kraus continues. “When Sophie Podolski was going through this intense period between 1969 and 1974, I was in the provinces in New-Zealand, I wasn’t yet culturally active. So I think I’ve come to her work more as a contemporary person discovering her as part of an intellectual, a literary, and an artistic tradition. But because I was alive during those years, I have an awareness that places like the Montfaucon Research Center – where Sophie Podolski ended up – existed. Places where you had these extremely intimate friendships. In the house people didn’t even have assigned rooms, they kind of rotated where they slept. It was all kind of familial and incestuous.”

“Joëlle herself had a very unusual relationship with Michel Bonnemaison, the key figure of the house. They lived and worked together for 40 years, but they were not a conventional couple. These possibilities of relationships and friendship that aren’t limited to the traditional couple, is something that I feel very close to. That inclination to live that way, to sort of take yourself out of the normal grid of progression and conventional ambition and to have a different ambition.”

Sophie Podolski had an unfailing belief in immediate writing, and doing and thinking, living and working fast

Behind the serious-sounding name of the Montfaucon Research Center was the house at Dageraadstraat 25 rue de l’Aurore, where Sophie Podolski became a frequent guest. Joëlle de La Casinière: “There were about five of us who formed the backbone of that house. It was a very large building with a lot of rooms. It has since been demolished, but at the time a very close-knit group of artists who shared an artistic affinity shacked up together there. We all had our own work, but we influenced each other profoundly. People like Al Berto, a Portuguese painter who became an important poet in Portugal, and Olimpia, a half-German, half-Italian painter and a committed gauchiste. The lynchpin was Michel Bonnemaison, who was 20 years older than all the others and who invited artists to do residences there. He was a beautiful person and a really cool guy, who was very interested in cultivating young people. He was a kind of father figure, but especially a friend, who made us read and taught us things. He was the centre of it all. There was a constant coming and going of friends and people who were travelling across Europe…"

"It was astonishing how very soon people simply knew where the house was, like a kind of stop on long journeys, a focal point in a period when Brussels was still provincial and dead – apart from places like the Smog, a bar/club on Koninklijke Prinsstraat/rue du Prince Royal, the Thalamus, and the Dolle Mol. And this was the extraordinary place where Sophie burst in during the late 1960s. She was an absolute artist, a prodigy who had already experimented with woodcutting in the style of Beardsley, Toulouse-Lautrec, or Picasso when she was only fourteen or fifteen. That was the baggage she brought with her when she came to us, and she started writing and drawing like a maniac. She didn’t really have her own room or studio in the house, but there was always somewhere for her to crash, and it is where she made almost all her work, in a period of five years, during her artistic peak.”

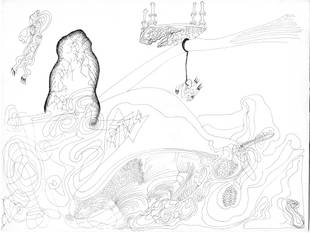

In Dans la maison (du Montfaucon Research Center) – an hour-long film that Joëlle de La Casinière made in 2016 using a mix of audio recordings of Sophie Podolski, photos of her work and of the residents, and 16mm footage of the empty house that she found tucked away in a closet somewhere – you get an idea of the goings-on there. It was a place where the revolution was imagined, where the sexual liberation was in full bloom – thanks to the many people who had triggered their own little May 68 at La Cambre –, and where Sophie Podolski absorbed it all like a sponge. Caroline Dumalin: “Sophie Podolski was not so much an intellectual or somebody who studied hard. She was more of a savant, somebody who possessed a spontaneous and intuitive culture, and who picked up an immense amount of what was going on around her and blended it all together.”

“She needed food for thought,” Joëlle de La Casinière confirms. “She was very curious and enthusiastic, was immersed in the atmosphere and debates in the house, and sympathized with the anarchist spirit of the place. But she was also a free spirit herself, who came and went, who would work extremely hard at the house for a few days and then go home to Bosvoorde/Boitsfort to be with her mother and sister, or disappear for a while just to be active or go out in the city, where she knew a lot of people. She was very much attached to her freedom and autonomy.”

Poetic improvisations

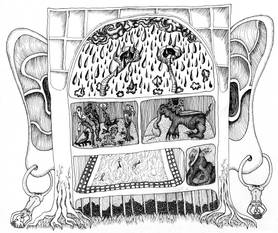

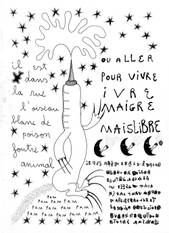

Sophie Podolski celebrated her freedom to the full at the house. “She always had her nose in a notebook. She wrote or drew on every single scrap of paper,” Joëlle de La Casinière says. “I have thousands of fragments of her writing, including in school exercise books. They are all poetic improvisations, which were written there, at that moment.” In 1972, these improvisations coalesced in a book, when Sophie Podolski’s Le pays où tout est permis was published by the Montfaucon Research Center. “She wrote that book in 1971. It only took her two months,” Joëlle de La Casinière tells us.

“For every ten of our years, she only needed one. Olimpia had been given two blank, bound books by an editor. She gave one to Sophie, and together they spent the summer at Olimpia’s parents’ chalet in Switzerland, and each wrote a book. Sophie opened hers, started writing on the first page, and didn’t stop until the pages ran out. Not a single page was torn out. It was an improvisation in the style of Thelonious Monk, one long, poetic stream into which she copied texts and drawings, creating a myth of freedom, anarchy, and another world.”

“Sophie Podolski had an unfailing belief in immediate writing, and doing and thinking, living and working fast,” Caroline Dumalin says. “You might consider it as a kind of écriture automatique, but she always said that she found things all over the place, and then processed them all in her own machine. Le pays où tout est permis is thus very subjective and idiosyncratic, but sometimes a reflection of the time does filter through. For example, she frequently refers to Frank Zappa and to herself and the people in the house as ‘freaks’, who were the counterparts to the hippies and who symbolically resisted bourgeois society. This was not limited to the artistic world, but even permeated the way you expressed yourself in the clothes you wore and your lifestyle.”

Sophie had an absolute need to create. But there was also an urgency in her work. She must have sensed something was going on

Writing was a living thing for Sophie Podolski. This also implies, however, that Le pays où tout est permis is not an easy or comfortable read, but a – sometimes violent – struggle. With time, the world, conventions and structures, relationships, identity, change, with the word and with oneself. A struggle that exudes an irresistible rhythm, which can be both hilarious and merciless at the same time, that you enjoy and that can disintegrate you; as complex and paradoxical as a living body.

“It’s like a transcription of a mental state, more than a composition,” Chris Kraus says. “It was all written in one go, it wasn’t revised. I have this image of her writing as though she was throwing handfuls of dirt up against the wall, just throwing, throwing, throwing, and some of the substances that come out, are blindingly brilliant and prophetic. Some of them make no sense, and then there will be this line that shines through the ages. To write this way, you need to reach a certain pitch. If you’re in a mundane sort of consciousness, you can do this kind of automatic writing, but no one’s going to want to read it. If you’re going to transcribe a consciousness, that consciousness has to be in some way charged and illuminated and larger than life.”

Truth and paradox

“Sophie, is this normal? Is this normal, Sophie?” we suddenly hear playfully and – in hindsight – very starkly in Dans la maison. “Almost everything that’s really deeply true is paradoxically true. It’s a trick for the mind to hold two conflicting thoughts at the same time. And it can be very painful,” Chris Kraus beautifully expresses it. In this sense, Sophie Podolski was a profound truth. “She contradicts herself all the time, but that doesn’t mean that either side is any less true,” Caroline Dumalin says, picking up on the idea. Sophie Podolski suffered from schizophrenia, a disease that dislocated her life and work.

“Her mother and sister realized very early that she was different. As an adolescent, Sophie was often arrested for disrupted public behaviour, admitted to hospitals, and pumped full of drugs. Each time, it was a quick and easy solution that was imposed in a very authoritarian way. On the other hand, she lived in an environment in which insanity was not necessarily a problem and actually fed into the work and creativity. This all resulted in the situation that there wasn’t really anywhere for her to recover properly. By the time she was 21, I think she was just exhausted, running on empty.”

“Her work exudes a vital necessity,” Joëlle de La Casinière says. “From her earliest years, she would constantly tell unbelievable stories, play pranks, and draw. She had her own palpable energy and an absolute need to create. But there was also an urgency in her work. She must have sensed something was going on. All the drugs that she took were to stimulate her to make her work. It was her way of taking care of herself."

I have this image of Sophie writing as though she was throwing handfuls of dirt up against the wall. Some of the substances that come out, make no sense, and then there will be this line that shines through the ages

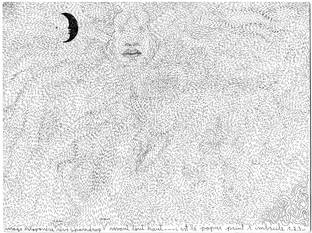

"She never really talked about her disease, though there were some allusions to it in her work. There is an extraordinarily beautiful drawing in which she wrote: ‘Mon génie s’effrite. Je ne me plains pas. Je dis seulement que j’ai mal.’ And of course there were the crises. The first time she was taken to hospital was in 1970, I think. It was very brief, but she worked extremely hard afterwards. We felt as though she had felt a warning shot."

"When she was 20, she was admitted to La Borde [an experimental psychiatric clinic near Paris, where patients actively participated in running the facility – KS], after which she disintegrated completely. In one year, very quickly and very violently. She was somebody who couldn’t bear to be locked up or constrained, by medication or by an administration. I think she ultimately committed suicide because she was suffering too much. Both physically, and because she knew that her art was going to disappear.”

“As a writer of high literary, poetic texts, you are reaching toward a kind of madness or dissolution of boundaries, or accessing a heightened consciousness. But you can’t really compare it with schizophrenia. It’s not good to romanticise it,” says Chris Kraus, who previously wrote about schizophrenia in I Love Dick, one of the most radical-critical, thought-provoking, and touching books about women and the relationships between men and women. “When I wrote that chapter in I Love Dick, I was trying to extend myself empathically to the world of the schizophrenic as far as I could, short of being one. But that’s a big gap. Like you’re standing on two opposite sides of a canyon, and you really can’t bridge it. Because a schizophrenic can’t control it and she can’t come back when she wants to.”

Fade to black

In late 1974, Sophie Podolski jumped out of the window of a building on Edelknaapstraat/rue du Page in Elsene/Ixelles. “It was heart-rending,” Joëlle de La Casinière tells us. “She didn’t die immediately, but hovered between life and death for ten days afterwards. We were all crushed by it. It was too difficult, and there came a point when we all shielded ourselves from it. Perhaps that is why Sophie’s work has remained my own private treasure for so long. I am convinced that she left all her work with us because she knew that we would preserve it. In fact, I recently bought some of her work from a bookseller who was selling it off little by little."

"Her work must stay together into the future. In the years after her death, the publication of her graphic poetry in the periodical Luna Park felt like a small mausoleum, but her name soon faded from memory. Now, with a new generation, there is more distance. Hopefully we can reawaken interest.”

Caroline Dumalin also realized that this moment is pregnant with possibility. “In addition to the exhibition, in which we try to elicit an associative way of reading and looking at the work, with a focus on Sophie Podolski’s visual work, a fragment from Joëlle de La Casinière’s film, audio of Sophie Podolski, and the original manuscript of Le pays où tout est permis, we are also publishing a catalogue with contributions by Chris Kraus, but also by author-curator Lars Bang Larsen and psychiatrist Erik Thys."

"Her work is still very relevant. Many of the taboos she attempted to break are still present, such as the relationship between high art and people with psychiatric fragility. The uninhibited, sometimes vulgar, and confrontational way she wrote about relationships and sexuality, or her personal visual mythology, which consists of hybrids of people and animals and people and machines, likewise still have great expressive power. Sophie Podolski treated issues in a very blunt manner. Completely free of taboos, but with the total realization that she was touching people.”

Sophie Podolski

- was born in 1953 as the daughter of an American mother and Eastern European father, into an artistic and bohemian environment

- grew up in Bosvoorde/Boitsfort with her sister and mother, who was a ceramic artist and taught at the academy a stone’s throw from their home

- left school very early because she was unable to settle in the context of an institution experimented with woodcutting between the ages of 14 and 15

- knocked at the door of the Montfaucon Research Center in 1969, becoming a regular visitor of the artistic community, immersed herself in the anarchist spirit and experimented with drugs, free love, and radical art

- at the same time led a nomadic existence in the city, where she was regularly picked up for divergent behaviour and briefly admitted to institutions

- witnessed the publication of her only book, Le pays où tout est permis, in 1972

- in only five years, created an insane amount of absolutely unique graphic poetry, mixing words and images

- was admitted to the psychiatric hospital La Borde in Paris in 1974

- disintegrated completely and committed suicide in late 1974

Exploring the country where everything is permitted

Caroline Dumalin (1986) is curator at the contemporary art centre Wiels.

Chris Kraus (1955) is an American artist who began her career in experimental film, but garnered global fame with the feminist cult classic I Love Dick, which The Guardian described as “the most important book about men and women written in the last century”, and which Jill Soloway adapted into a TV series for Amazon.

Joëlle de La Casinière (1944) is a Brussels-based filmmaker who has travelled the world for her work. In the 1960s and 1970s, she and ichel Bonnemaison were the driving forces behind the artistic community Montfaucon Research Center, where Sophie Podolski made the majority of her work. The archives that Sophie left there constitute the raw materials for the current exhibition at Wiels.

> Sophie Podolski: Le pays où tout est permis. 20/1 > 1/4, Wiels, Forest

Read more about: Vorst , Expo , Chris Kraus , Sophie Podolski , Caroline Dumalin , Joëlle de La Casinière , Wiels

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.