The internationally renowned French photographer Mathieu Pernot (Prix Cartier-Bresson 2019) is making a stop-off at the Jewish Museum of Belgium with “Something Is Happening”. The last year in the life of a refugee camp, told in several different voices.

© Mathieu Pernot

January 2020. The island of Lesbos in the Aegean sea. The Moria camp is dangerously overpopulated. Designed to hold 2,000 migrants, it has just passed the 20,000 mark. The luckiest stay inside the camp but the vast majority of the asylum seekers are cut off from its infrastructure, condemned to live in makeshift shelters pitched in the neighbouring olive grove. The wait is long, especially in winter. People know when they have arrived in the “Moria Jungle”, but no one knows when they will leave. They could be waiting more than two years.

A photographer weaves between the patched tents; we recognise him by his satchel: Mathieu Pernot. The French artist has come in search of the next chapter in a story about migration, pieces of which he began to collect in his home country. In Calais, in the “Jungle”. In Paris, at other improvised camps. “I realised that I had to keep going, to leave France.”

In Moria, Mathieu Pernot quickly became friends with Idriss, a young multilingual and resourceful Somalian who turned out to be the perfect fixer. Together, they paid visits to tent after tent, going from campfire to campfire, back and forth along the paths that wind between the olive groves. “I think I'm quite a solitary, timid, and reserved person and at the same time, I am very interested in my surroundings,” says the artist-photographer. “What is beautiful about photography is that you can immerse yourself in a world that is not your own. Get in touch with it and try to untangle the threads of reality, and to weave them back together.”

DRIVING OFF THE COLD

Immersed in the Moria camp (“I had been told that going there was forbidden”), Mathieu Pernot himself felt a sense of “vulnerability”. “I become the minority within the minority. If I didn't have people watching over me, anything could happen to me.” Observing and listening with care, the photographer documents the fact that “something is happening”. That is the title of his exhibition, curated with great sensitivity by Bruno Benvindo, at the Jewish Museum of Belgium, and of his book, published by GwinZegal.

© Mathieu Pernot

| Mathieu Pernot: “To me, that's what photography is about: coming face to face with something that could disappear the next day, and when it succeeds in capturing it, maybe then it has accomplished its mission.”

Men, women, and children, wrapped in blankets, their eyes closed as they wait for time to pass on a makeshift bed. Families and companions drive off the cold with flames. Most of them are smiling, others not so much. Some of them look straight into Mathieu Pernot's camera lens, many do not. So, nothing is happening then? Quite the opposite. Successive images of the same situation all look the same, but only at first sight. To enter the camp, for example, people must cross a wooden gangway overhanging a trash heap. Mathieu Pernot immortalised several of these crossings, each time made by a different person. Every crossing matters. So does every destiny.

The photographer does not look for the perfect image because he simply does not believe in it. “We need powerful images. But a photograph excludes what is beyond the frame. Everything it does not show is as important as what it does show.” No decisive moment, no iconic images, no spectacular scenes brimming with pictorial references. Just images. The poetic traces of lives held in suspense. “What I create are the archives of tomorrow,” says Pernot. That is as true of his time in the Moria camp as it was when, over the years, he photographed a Roma family in Arles (Les Gorgan) or when he visited a jail in Paris (La Santé).

HOPE IS BURNING

In September 2020, a fire started by the refugees reduced their camp to ashes. “Something” was happening. Photojournalists rushed to the site. Not Mathieu Pernot. “Nothing is more beautiful than a fire and I should know.” The photographer would experience the Moria Jungle revolt, the protests, the attacks, and the fires through videos shot on phones by refugees with whom he had remained in contact. “I prefer to be a messenger for those who experienced the events, to share their point of view and give them a voice.”

We need powerful images. But a photograph excludes what is beyond the frame. Everything it does not show is as important as what it does show

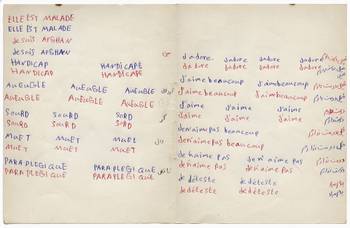

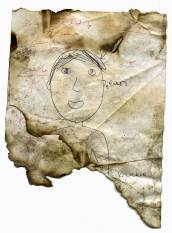

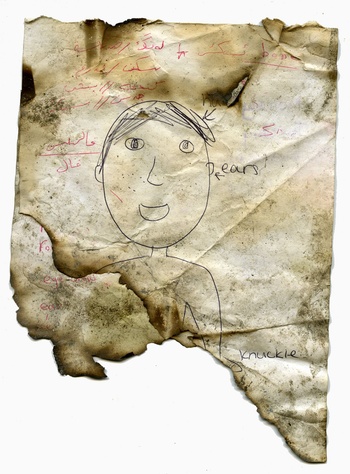

Mathieu Pernot's work is enhanced by the inclusion of images taken by other people and documents that once belonged to other people. In the exhibition at the Jewish Museum of Belgium, he brings his photographs into a dialogue with school notebooks that were rescued at the last minute from a pile of ashes in the Calais Jungle, and videos shot by migrants during their journey towards a better life, such as the chillingly violent film of a coast guard boat purposely colliding with an inflatable life raft full of migrants, as well as the notebooks of Afghan refugees determined to learn French.

It is an ethical way of working: “It's a way of recognizing that you are not the only narrator.” But that's not all. “It is not a statement. I think that it is also entirely possible to have no extra narrators. I choose to show these images and documents because I find them incredibly powerful, with a lot to say, and because I like to compile things that, together, make a story.”

© Mathieu Pernot

| Mathieu Pernot’s work is enhanced by the inclusion of images taken by other people and documents that once belonged to other people. “It’s a way of recognizing that you are not the only narrator.”

A messenger of stories, a documentary photographer in the true sense of the term, Mathieu Pernot is, above all, a photographer of other people. “My experience is a million miles from that of the people I photograph. Everything around me is very dull and uninteresting to me as a photographer. I am happy with my story, but I have nothing to say about my story or my family. If we could only be interested in what we are and where we come from, I wouldn't do anything,” says Pernot, adding: “Art is full of encounters and stories. What is important, above all, is to ensure that everyone can tell their story in the same way.”

LANDSCAPE AFTER THE BATTLE

The third and final act of the Greek tragedy: after September's fire, the Moria camp is in ruins. Mathieu Pernot returns to the site at the same time as some migrants who have come to salvage what remains of it. The Moria chapter is closed. The Jungle will become an olive grove once more. Those who have come across Mathieu Pernot's work before will quickly recognise the thread that runs between these ruins. If it is not buildings riddled with bullets in post-civil war Lebanon, it is cities full of derelict homes, demolished along with their utopias, or Gypsy caravans in flames. “To me, that's what photography is about: coming face to face with something that could disappear the next day, and when it succeeds in capturing it, maybe then it has accomplished its mission.”

© Mathieu Pernot

| “A ruin is a fragile space, a suspended state between two situations”, says Mathieu Pernot.

In 2019, thanks to the Prix Cartier-Bresson, Mathieu Pernot successfully developed a project entitled Le Grand Tour. A journey through the ancient cities of the Middle East that took him from Tripoli in Lebanon (the city where the artist's father was born) to Mosul and Homs, in search of the “new ruins” that, sadly, inaugurated the twenty-first century.

“A ruin is a fragile space, a suspended state between two situations”, says Mathieu Pernot. Amid the rubble there is “a breath-taking fragility”. “The people I photograph hold themselves upright and are the actors of their lives. Their lives are extremely fragile, but they embody an incredible power.” He adds: “I find that life is never so powerful as when it is embodied by those who have experienced how fragile it is.”

MATHIEU PERNOT: SOMETHING IS HAPPENING

>19/9, Jewish Museum of Belgium, www.mjb-jmb.org

Mathieu Pernot: Something Is Happening

Read more about: Expo , Mathieu Pernot , Something Is Happening , Jewish Museum of Belgium