Heatwaves are becoming more frequent and extreme, including in Brussels. They are also much more deadly in the city than outside. How can you still make the city a cool place? We found answers in Vienna, at 36 degrees Celsius. "Turn the city into a sponge."

© Kris Hendrickx/BRUZZ

| Florian Reinwald (BOKU) in Aspern Seestadt

It is only 9 o'clock in the morning when we arrive at the Schlingermarkt in the Floridsdorf district of Vienna. Yet temperatures are already hovering around 25 degrees. What did our magazine editor say when we left on our climate trip? "I hope you end up in one of those intense heatwaves." We had smiled approvingly. But here in continental Vienna, we're not laughing anymore, especially when the temperature doesn't even want to drop below 30 °C at night later that week. And what is true for us is true for the entire city: by 2030 already, Vienna fears 1,000 heat deaths a year, by no means a laughing matter.

© Kris Hendrickx/BRUZZ

| The Schlingermarkt in Vienna: benches are surrounded by large planters in which, among other things, trees grow. Canopies, along with the vegetation, provide shade.

Back to the Schlingermarkt. The paved square in a working-class neighbourhood has a number of old-fashioned enclosed market pavilions. One of its sides is dominated by the Schlingerhof, one of many Viennese residential complexes rented out on social terms. Most residents do not have terraces nor balconies.

The entire square consists of asphalt, except for one corner where a green oasis is emerging. An ensemble of benches is bordered by large plant containers in which trees, among other things, are growing. Tarpaulins were installed above the benches, casting shadow together with the vegetation. With the press of a button, you are treated to a refreshing cloud of water mist. Next to the green island of shade is another water tap.

In the seating area, visitors, often residents of the Schlingerhof, are coming and going. "I don't have my own house, garden or terrace," says Eduard (61), who watches the passers-by from where he is sitting. "This is pretty much my living room." Meanwhile, in another corner of the urban living room, a couple is getting cozy.

"What are you thinking?"

We are in a Tröpferlbad 2.0, a permanent installation financed by the city of Vienna. "It is a cooling space, but also a social space, where people can meet without the need to consume", explains Doris Schnepf of architecture company Green4Cities. "And residents were able to assist in deciding what the installation should look like."

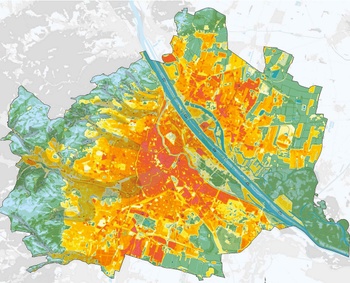

© wien.orf

| A heat map of Vienna. Similar to Brussels, it's primarily the historical center and the densely built neighborhoods around it that experience significant warming during heatwaves. The Danube and the Danube Canal provide some cooling, but this effect remains relatively localized.

We found out a little later that this also makes the local residents feel responsible. A neighbour comes down from his flat to admonish us: what are we thinking, sitting on the back and putting our feet on the bench where the residents should then sit? We meekly obey and sit a level below.

The cool oasis works, that much is clear. Vienna currently has two public prototypes, but that number is likely to grow over the next few years. Still, Schnepf realises such an installation is not the big solution to the warming city. "But it is something that you can quickly achieve and that also has an effect."

"You have to make plans that involve all city departments, and also public and private actors"

The location of the cool oasis is also characteristic of the city of Vienna's general policy when it comes to heat stress in the city: that policy tries to protect residents in vulnerable neighbourhoods in particular, by converting those neighbourhoods first. After all, heat is also a social problem.

Today, those wishing to cool the city down have a range of options at their disposal. In cities like Seville, tarpaulins cast shadows over narrow streets. More and more governments are experimenting with painting surfaces white to reflect the sun. Traditional Greek and other Mediterranean villages are not snow-white by chance. When choosing building materials, the albedo factor (the degree to which light is reflected, literally 'whiteness') has therefore become increasingly important in recent years.

"In this neighbourhood, we built the metro first and then the district. That way you don't make new residents immediately dependent on cars"

You can install misting systems, as Vienna does. You can find them in various forms at over three hundred spots in the city: misting installations that activate automatically when the temperature climbs above 27°C for several days. The refreshing effect is real, but very local, and "of course it's fun for a politician to inaugurate them," we sometimes hear sneering.

The good old tree

The cooling technology of the future is one that we have always had: greenery in public spaces. Within that category, there is one clear-cut champion: large trees with real foliage. They provide shade, and the evaporation through the leaves also provides extra cooling. Vienna may have quite a few parks, but like Brussels, the city also has many streets without a single tree, especially in the city centre. It is why the Austrian capital wants to replant 25,000 trees this legislative term. And in Brussels? It goes as far as a declaration of intent to plant more, without giving a figure.

© Kris Hendrickx/BRUZZ

| Benedikt Kiesling from Green4Cities takes us to a test installation outside Vienna, where a cooling road surface is being tested. The CoolWays sidewalk maintains a comfortable temperature, while on a regular sidewalk, it quickly becomes uncomfortable to walk on.

Planting trees is one thing, making sure they survive is another. "About a fifth of new plantings don't make it," admits urban climatologist Max Wittkowski. "And as we plant more and more XL trees, which provide instant shade, that figure rises even higher. Because larger trees also have a harder time adapting to a new environment."

To still give new trees more chances, Vienna is increasingly applying the Schwammstadt principle: the sponge city. This involves giving city trees an extra-large space for their roots, which for street trees extends below the road surface. This is then filled with larger stones and water-containing material. The root space thus functions as a large storage sponge for the tree. An additional advantage: the stored water reduces the pressure on the sewer system during heavy rains, and the tree can evaporate and thus cool down for a longer period of time.

Sponge city. It is a term that has been used more and more often in recent years when talking about climate adaptation. Using the subsoil as one big sponge - which retains rainwater, provides vegetation with water, counteracts floods and also cools the environment - is a principle that is not limited to street trees. Parks, flower and plant beds or gardens: with the right construction, they can all act as large urban sponges. Such a water retardant also has the immediate advantage of being effective against various effects of global warming. Flooding, heatwaves, drought? The sponge knows what to do.

The fact that cities heat up so quickly is, of course, due to the enormous amount of stone that stores heat and remains warm until late at night. But it could also be part of the solution. Benedikt Kiesling of Green4Cities takes us to a pilot plant outside Vienna, where a cooling road surface is being tested. Under a scorching sun, four different test pavements lie side by side, each with a layer of water underneath and a sheet of waterproof foil beneath. Sitting on the pavement with the plain paving stone quickly become uncomfortable under our hindquarters. On the strip next to it, made of specially developed water-absorbing stones with open joints, the temperature turns out to be very comfortable. "With CoolWays, you could cool the pavement as well as the whole street," Kiesling says. Our sitting test tells us it's promising.

© Kris Hendrickx/BRUZZ

| The Praterstern traffic junction in Vienna received a makeover: it was significantly de-paved, dozens of trees were added, and the water playground with 300 sprayers has proven to be very popular.

Angry neighbours

A new day, a new heat record. Meanwhile, as the temperature climbed to 36°C (in the shade), we met with researcher and urban planner Florian Reinwald (BOKU) in Aspern Seestadt. Reinwald is also co-author of the Vienna strategy to contain the heat island effect, a document that does not really exist for Brussels. "Strategies, that's what we are good at here," Reinwald says without irony.

The newly built Seestadt area, around a newly dug lake, is one of the largest urban development areas in Europe, with room for 25,000 new residents and another 20,000 workplaces. A point of reference? The much-discussed Josaphat friche will have a population of less than 5,000, if there is to be any construction at all.

Aspern Seestadt is a fascinating place. To see what should be done to make a new urban area climate-proof, but also where things can go wrong. "In this finished part, asphalt initially predominated in the pedestrian zones," Reinwald explains. "In response, the new residents protested so loudly that the new city council ended up reopening a large section to create green zones and plant large, 30-year-old XXL plane trees." The researcher knows city planning is a slow process and often lags behind new insights, "Even with the overgrown facades you see here, it was often experimentation in the beginning. What we did well, however, was to build the metro first and then the neighbourhood. That way you don't make new residents immediately dependent on cars."

In a part of the Seestadt that has yet to be built, a large covered arcade overlooking the lake is also planned. "That too is climate-proof planning: it's a place that protects you from rain as well as sun and heat."

© Kris Hendrickx/BRUZZ

| Urban planner Florian Reinwald (BOKU) in Aspern Seestadt. This new development area, around a newly excavated lake, is one of the largest urban development areas in Europe, accommodating 25,000 new residents and an additional 20,000 workplace.

A fan for the city

Greenery and trees are crucial for a cool city, but it is not the only recipe. What do you do in your flat when it is scorching hot both inside and outside? You might reach for a fan. That ventilation can also be done on a larger scale, by factoring dominant wind currents into planning. "In the finished district, this has not yet been taken into account," laments Reinwald, spreading out a neighbourhood plan on the bottom of the local skate park. "In some places, you risk overheating, whereas others have too much wind. Look at the local cigarette dealer: at first, he couldn't open his door due to the sand that was blowing against it."

In the future area of Seestadt, Reinwald & co. managed to execute a microclimatic analysis and make interventions. In the new district, cooler air currents from outside the city are routed through the neighbourhood. "This often involved minor changes: leaving a small gap between two buildings or changing the location of a row of trees so that it does not block air flows, but directs them to a particular spot. Nobody was against those changes, it's mainly a matter of having that knowledge and sharing it. Whether such wind analysis would also be useful in Brussels? "There is wind everywhere."

© Kris Hendrickx/BRUZZ

| You can find misting systems in various forms at over three hundred locations in Vienna: spray installations that are automatically activated when the temperature remains above 27°C for several days.

The analysis of wind currents and their effect is not only done at the level of the neighbourhood itself. "We are also looking at whether that large, new urban area in itself could also be an obstacle to the cooling of the city centre further down the road," explains Reinwald. "But it turned out not to be the case."

Can the researcher say anything meaningful about the controversial Josaphat site dossier in Brussels? We want to know. "Only in general terms: a green area already cools down its surroundings starting around 1 to 2 hectares, so those 25 hectares certainly have an effect. But if you ask me whether you can build in an intelligent way there so that you keep the cooling and ventilation towards the centre, my answer is also: definitely."

Rummikub in the cooling space

The whole arsenal of measures cooling down public spaces is much needed for the city of the future. But the Vienna heatwave makes one thing clear: it is not enough. At 36 degrees, it gets too hot for vulnerable residents even in the parks, not to mention the nights in a heated-up residence in the city centre. Cool indoor spaces will therefore have to be an essential part of cities' heat strategy in the future.

© Kris Hendrickx/BRUZZ

| A day center for retirees in Greiseneckergasse added a cooling feature. Each Cooling Zone has at least two spaces: one for socializing - a group of cheerful elderly ladies is playing Rummikub there - and one with loungers for resting.

Vienna, meanwhile, has started to do just that. A 'Cooling Zone' has been set up in two places in the city, where anyone who wants to can catch their breath. We visit one in Greiseneckergasse, where a day centre for pensioners got a cooling function. Each Cooling Zone has at least two areas: one for meeting people - a group of middle-aged ladies are playing Rummikub - and one with deckchairs for resting. There are free drinks and the thermometer shows a pleasant 26 °C. Next year, the network may be expanded to a dozen. Other cities such as Barcelona are quite a bit further ahead in this respect. The Catalan capital, meanwhile, has a network of two hundred refugios climáticos (climate shelters), mostly in public buildings.

Such a network is needed, believes Bernd Vogl, President of the Austrian Climate and Energy Fund. After all, existing older homes will not suddenly become easy to cool overnight. And traditional air conditioning is not a climate solution either. Vogl is therefore pinning his hopes on large school complexes that can be cooled in an environmentally friendly way and serve as shelters, he says in an interview in this issue (see here).

A week in Vienna makes it clear that a lot is happening in the Austrian capital. Yet we also want to know from all our interlocutors what the city still needs to do better. The answer is strikingly similar and applies to most cities with heat stress: the measures we already know about today need to be implemented on a much larger scale.

"You have to make plans that involve all city departments, that are executed at least at the level of an entire district and that involve both public and private actors," says Doris Schnepf, as we sit in the shadow of the Tröpferlbad. "In such a project, you then have to talk not only about green spaces, but also about energy and traffic. After all, space for new green space in the city centre is limited. And you have to do it co-creatively, with the residents. Then you can get results."

Read more about: Brussel , Milieu , Gezondheid , Klimaatbestendige stad , wenen , klimaatverandering , opwarming van de aarde , levenskwaliteit

Fijn dat je wil reageren. Wie reageert, gaat akkoord met onze huisregels. Hoe reageren via Disqus? Een woordje uitleg.